554:. The state ensures security of life, limb and property; it brings within reach of every individual many necessaries of life which he could not produce by himself; and it sets free sufficient time and energy for the higher development of human powers. Now the existence of a state depends upon a kind of implicit agreement on the part of its members or citizens to obey the sovereign authority which governs it. In a state no one can be allowed to do just as he pleases. Every citizen is obliged to obey its laws; and he is not free even to interpret the laws in a special manner. This looks at first like a loss of freedom on the part of the individuals, and the establishment of an absolute power over them. Yet that is not really so. In the first place, without the advantages of an organised state the average individual would be so subject to dangers and hardships of all kinds and to his own passions that he could not be called free in any real sense of the term, least of all in the sense that Spinoza used it. Man needs the state not only to save him from others but also from his own lower impulses and to enable him to live a life of reason, which alone is truly human. In the second place, state sovereignty is never really absolute. It is true that almost any kind of government is better than none, so that it is worth bearing much that is irksome rather than disturb the peace. But a reasonably wise government will even in its own interest endeavour to secure the good will and cooperation of its citizens by refraining from unreasonable measures, and will permit or even encourage its citizens to advocate reforms, provided they employ peaceable means. In this way the state really rests, in the last resort, on the united will of the citizens, on what

88:

175:, directly challenging religious authorities and their power over freedom of thought. He published the work anonymously, in Latin, rightly anticipating harsh criticism and vigorous attempts by religious leaders and conservative secular authorities to suppress his work entirely. He halted the publication of a Dutch translation. One described it as being "Forged in hell by the apostate Jew working together with the devil". The work has been characterized as "one of the most significant events in European intellectual history", laying the groundwork for ideas about liberalism, secularism, and democracy.

472:

erroneous, and inconsistent with itself, and that we possess but fragments of it" roused great storm at the time, and was mainly responsible for his evil repute for a century at least. Nevertheless, many have gradually adopted his views, agreeing with him that the real "word of God", or true religion, is not something written in books but "inscribed on the heart and mind of man". Many scholars and religious leaders now praise

Spinoza's services in the correct interpretation of Scripture as a document of first rate importance in the progressive development of human thought and conduct.

29:

1512:

1500:

1488:

218:(1633–1669), had published two works scathing of religion. Because they were published in Dutch rather than Latin, and therefore accessible to a much wider readership, he quickly came to the attention of religious authorities, arrested, and thrown into prison, where he quickly died. His death was a hard blow for Spinoza and his reaction was to commence writing in 1665 what became the

239:

459:, properly understood, gave no authority for the militant intolerance of the clergy who sought to stifle all dissent by the use of force. To achieve his object, Spinoza had to show what is meant by a proper understanding of the Bible, which gave him occasion to apply criticism to the Bible. His approach stood in stark contrast to contemporaries such as

393:. Whereas, he contends, the goal of theology is obedience, philosophy aims at understanding rational truth. Scripture does not teach philosophy and thus cannot be made to conform with it, otherwise the meaning of scripture will be distorted. Conversely, if reason is made subservient to scripture, then, Spinoza argues, "the

533:. In his view, because the state no longer existed, its constitution could no longer be valid. He argued that the Torah was thus suited to a particular time and place; because times and circumstances had changed, the Torah could no longer be regarded as a legally binding document on the Jewish people.

811:

Which in

English would mean: Containing several dissertations, without prejudice to the freedom of the Philosophers or to Piety, and to the Peace conceded by the Republic; but also dealing with the Peace of the Republic itself, which without Piety cannot properly continue. To this the Latin text of 1

488:

he does not refer to himself as a Jew, although a number of

Christians labeled him a Jew. He only speaks of "the Hebrews" or "the Jews" in third person. His knowledge of Hebrew, his yeshiva studies of Jewish scripture, and his insider knowledge of how religious authorities exercised power by claiming

647:

and needs analogous checks. On the whole, Spinoza favours democracy, by which he meant any kind of representative government. In the case of democracy, the community and the government are more nearly identical than in the case of monarchy or aristocracy; consequently a democracy is least likely to

213:

functioned as head of state and was in favor of policies of religious toleration, which had helped fuel prosperity. Jews could practice their religion openly and were an integral part of the commercial sector. There were also a great number of

Christian sects that contributed to the religious and

471:

and no rival authority to the civil government of the state, rejected also all claims that

Biblical texts should be treated in a manner entirely different from that in which any other document is treated that claims to be historical. His contention that the Bible "is in parts imperfect, corrupt,

574:

and all others, provided they are not fanatical believers or unbelievers. It is ostensibly in the interest of freedom of thought and speech that

Spinoza would entrust the civil government with something approaching absolute sovereignty in order to effectively resist the tyranny of the militant

565:

Spinoza sometimes writes that the state ought to be accorded absolute sovereignty over its subjects. But that is due mainly to his determined opposition to every kind of ecclesiastical control over it. Though he is prepared to support what may be called a state religion, as a kind of spiritual

602:

he states explicitly that "human power chiefly consists in strength of mind and intellect" — it consists in fact, of all the human capacities and aptitudes, especially the highest of them. Conceived correctly, Spinoza's whole philosophy leaves ample scope for ideal motives in the life of the

583:

One of the most striking features in

Spinoza's political theory is his basic principle that "right is might." This principle he applied systematically to the whole problem of government, and seemed rather pleased with his achievement, inasmuch as it enabled him to treat political theory in a

306:

The work comprises 20 named chapters preceded by a preface. The majority of chapters deal with aspects of religion, with the last five concerning aspects of the state. The following list gives shortened chapter titles, taken from the full titles, in the 2007 edition of the

214:

intellectual ferment of the

Republic. Some dissenters began openly challenging religious authorities and religion itself, as Spinoza had done, leading to his expulsion from the Jewish community in Amsterdam in 1656. A like-minded friend and kindred intellectual spirit,

298:, prepared the edition by 1671 and sent it to the publisher; Spinoza himself intervened to prevent its printing for the moment, since the translation could have put Spinoza and his circle of supporters in increased danger with authorities.

278:

The treatise was published anonymously in 1670 by Jan

Rieuwertsz in Amsterdam. In order to protect the author and publisher from political retribution, the title page identified the city of publication as Hamburg and the publisher as

545:

that if each man had to fend for himself, with nothing but his own right arm to rely upon, then the life of man would be "nasty, brutish, and short". The truly human life is only possible in an organised community, that is, a

270:, who had visited him in the Netherlands and they continued the connection via letters, telling him about the new work. Oldenburg was surprised and Spinoza wrote his justifications for the diversion from metaphysics. The

447:

by Jews. He provided an analysis of the structure of the Bible which demonstrated that it was essentially a compiled text with many different authors and diverse origins; in his view, it was not "revealed" all at once.

388:

In the treatise, Spinoza put forth his most systematic critique of

Judaism, and all organized religion in general. Spinoza argued that theology and philosophy must be kept separate, particularly in the reading of

274:

is a frontal assault on the power of theologians underpinned by Scripture. Spinoza wanted to defend himself against charges of atheism. He sought the freedom to philosophize, unhindered by religious authority.

137:. Its aim was "to liberate the individual from bondage to superstition and ecclesiastical authority." In it, Spinoza expounds his views on contemporary Jewish and Christian religion and critically analyses the

671:

and officially banned the following year. Harsh criticism of the TTP began to appear almost as soon as it was published. One of the first, and most notorious, critiques was by Leipzig professor

197:

put pressure on civil authorities to curtail freedom of expression and the circulation of ideas to which they objected. In the political sphere conservatives sought to restore the position of

588:. The identification or correlation of right with power has caused much misunderstanding. People supposed that Spinoza reduced justice to brute force. But Spinoza was very far from approving

507:

explanation as to how the Jewish people had managed to survive for so long, despite facing relentless persecution. In his view, the Jews had been preserved due to a combination of

193:

was under strain in the mid-seventeenth century. War with England over trade and imperial dominance affected the Northern Netherlands' prosperity. The conservative leaders of the

518:

He also gave one final, crucial reason for the continued Jewish presence, which in his view, was by itself sufficient to maintain the survival of the nation forever:

480:

Spinoza had been permanently excommunicated from the Jewish community in Amsterdam in 1656, having previously been raised in that community and educated in a

161:, while the state remains paramount within reason. The goal of the state is to guarantee the freedom of citizens. Religious leaders should not interfere in

439:; he felt that all organized religion was simply the institutionalized defense of particular interpretations. He rejected in its entirety the view that

287:, the language of European scholars of the era. To reach beyond the scholarly readership in the Dutch Republic, publication in Dutch was the next step.

226:

is much more accessible and deals with religion and politics rather than metaphysics. Scholars have suggested that the text of the TTP incorporates the

1128:

Naturalism and its political dangers: Jakob Thomasius against Spinoza's Theological-Political Treatise. A study and the translation of Thomasius' text

408:, have only natural explanations. He argued that God acts solely by the laws of God's own nature and rejected the view that God acts for a particular

415:. For Spinoza, those who believe that God acts for some particular end are delusional, projecting their hopes and fears onto the workings of nature.

1065:

939:

635:. Each has its own peculiarities and needs special safeguards, if it is to realise the primary function of a state. Monarchy may degenerate into

1242:

1453:

87:

1515:

1032:

985:

1563:

1568:

1323:

1548:

1119:

Steven Nadler, A Book Forged in Hell: Spinoza's Scandalous Treatise and the Birth of the Secular Age. Princeton UP, 2011, p231.

648:

experience frequent collisions between the people and the government and so is best adapted to secure and maintain that peace.

1491:

566:

cement, his account of this religion is such as to make it acceptable to the adherents of any one of the historic creeds, to

1294:

1349:

738:

and Michael Silverthorne with introduction and notes also by Israel in the Cambridge Texts in History of Philosophy series.

1503:

1558:

530:

489:

special knowledge of sacred texts, meant Judaism was a salient target for his defense of individual freedom of thought.

660:

ever had political support of any kind, with attempts being made to suppress it even before Dutch republican magistrate

1553:

1445:

1357:

1129:

923:. Ed. Jonathan I. Israel. Trans. Michael Silverthorne and Jonathan Israel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2007.

727:

1982 by Samuel Shirley, with an introduction by B. S. Gregory (Brill, Leiden). Latter added to his translation of the

1230:

1205:

1181:

1167:

928:

529:

Spinoza also posited a novel view of the Torah; he contended that it was essentially a political constitution of the

91:

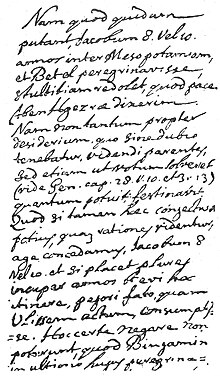

Manuscript notes by Spinoza on Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, chapter 9. Adnotatio 14. "That some people think that

1573:

1340:

222:. Heeding the danger of writing in Dutch, Spinoza's treatise is in Latin. Unlike the dense text of the Ethics, the

603:

individual and of the community. However, Spinoza considers only men full citizens, as outlined in his unfinished

684:

1459:

1054:, Chapter XIII: "Of the Natural Condition of Mankind as Concerning Their Felicity and Misery The truly human"

816:(By this we know that we dwell in God, and that God dwells in us, because he has given us of his own Spirit.)

1316:

496:. To Spinoza, all peoples are on par with each other, articulating a key element of what came to be called

206:

75:

1050:

806:

Quibus ostenditur Libertatem Philosophandi non tantum salva Pietate, et Reipublicae Pace posse concedi:

435:, but also of the so-called higher criticism of the Bible. He was particularly attuned to the idea of

697:

493:

1543:

526:

expression of bodily marking, a tangible symbol of separateness which was the ultimate identifier.

288:

1583:

1309:

814:

Per hoc cognoscimus quod in Deo manemus, et Deus manet in nobis, quod de Spiritu suo dedit nobis.

718:

of Spinoza, an abriged version, with introduction and notes, that includes the full text of the

1413:

975:

1381:

665:

555:

230:("defense") he had written in Spanish after his expulsion from the Jewish community in 1656.

194:

167:

1466:

432:

1511:

1271:

1263:

639:

unless it is subjected to various constitutional checks which will prevent any attempt at

623:

Spinoza discusses the principal kinds of states, or the main types of government, namely,

8:

1538:

1373:

1301:

828:, Amsterdam: Wereldbibliotheek, 1997. Translation in Dutch by F. Akkerman (1997), p. 446.

781:

720:

680:

585:

464:

134:

28:

700:

with introduction and notes (Trübner & Co., London). See below for the full text in

397:

of a common people of long ago... will gain a hold on his understanding and darken it."

280:

141:, especially the Old Testament, which underlies both. He argues what the best roles for

1578:

1393:

1252:(English translation by A. H. Gosset, Introduction by Robert Harvey Monro Elwes, 1883)

1156:

612:

312:

1218:. Ed. Isadore Twersky and Bernard Septimus. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1987.

1286:

1226:

1201:

1198:

A Book Forged in Hell: Spinoza's Scandalous Treatise and the Birth of the Secular Age

1177:

1163:

952:

924:

856:

A Book Forged in Hell: Spinoza's Scandalous Treatise and the Birth of the Secular Age

770:

154:

765:

760:

595:

443:

composed the first five books of the Bible, called the Pentateuch by Christians or

215:

184:

133:(1632–1677). The book was one of the most important and controversial texts of the

104:

992:

735:

672:

263:

202:

142:

1276:

598:) means a great deal more than physical force. In a passage near the end of his

1332:

1000:

731:, with introduction and notes by Michael L. Morgan (Hacket Publications, 2002).

547:

243:

190:

172:

130:

67:

1247:

1532:

1473:

1193:

1046:

989:. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 687–691.

980:

851:

755:

668:

661:

608:

594:. In the philosophy of Spinoza the term "power" (as should be clear from his

542:

267:

210:

258:. Unlike the abstract composition of that work as a mathematical proof, the

559:

551:

523:

519:

1430:

676:

628:

590:

578:

460:

424:

295:

129:, is a 1670 work of philosophy written in Latin by the Dutch philosopher

96:

1255:

1160:

Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity, 1650-1750

467:, and militant clerics. Spinoza, who permitted no supernatural rival to

1435:

775:

701:

512:

497:

456:

292:

198:

974:

946:

809:

sed eandem nisi cum Pace Reipublicae, ipsaque Pietate tolli non posse.

1425:

1419:

1401:

1282:

Contains a version of this work, slightly modified for easier reading

745:

of Spinoza (Princeton University Press; first volume issued in 1985).

644:

640:

632:

571:

504:

409:

394:

390:

284:

158:

150:

624:

436:

405:

401:

262:

is more discursive and accessible to readers of Latin. He wrote to

227:

162:

146:

1281:

1407:

1084:. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2018, p. 495

636:

508:

481:

1031:, G. Allen & Unwin ltd., 1928, p. 289. See also John Laird,

991:— see also A. Wolf's, "Spinoza, the Man and His Thought", 1933;

1277:

Benedict (Baruch) Spinoza – Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

468:

428:

400:

Spinoza held that purportedly supernatural occurrences, namely

100:

664:'s murder in 1672. In 1673, it was publicly condemned by the

567:

444:

440:

138:

92:

47:

343:

Chapter 8. Pentateuch, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, Samuel, Kings.

1331:

1188:

Spinoza's Theological-Political Treatise: A Critical Guide

238:

165:. Spinoza interrupted his writing of his magnum opus, the

1295:

Note on the text and translation – Cambridge Books Online

484:. After his expulsion, he never sought to return. In the

1223:

Spinoza, Liberalism, and the Question of Jewish Identity

997:

Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow, and the Feeling Brain

839:

Spinoza, Lberalism, and the Question of Jewish Identity

618:

579:

Human power consists in strength of mind and intellect

1007:, Ox Bow Pr., 1928; Ray Monk & Frederic Raphael,

1260:(English translation by Robert Harvey Monro Elwes)

1005:

The Philosophy of Spinoza: The Unity of His Thought

370:Chapter 17. The Hebrew state in the time of Moses.

233:

171:, to respond to the increasing intolerance in the

858:. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2011, 231

250:Spinoza had been working on his magnum opus, the

1530:

999:, William Heinemann, 2003, esp. ch. 6, 224–261;

972:

897:, p. 18 citing Spinoza's letter 30 to Oldenburg.

346:Chapter 9. Further queries about the same books.

423:Spinoza was not only the real father of modern

1200:. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2011.

1097:. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2023, 895-96

707:1883 by R. H. M. Elwes in the first volume of

584:scientific spirit, as if he were dealing with

340:Chapter 7. On the interpretation of Scripture.

1317:

1190:. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2010.

1186:Melamed, Yitzhak and Michael Rosenthal, eds.

841:. New Haven: Yale University Press 1997, 197

741:2016 by Edwin Curley in the second volume of

675:in 1670. Conversely, the British philosopher

643:. Similarly, Aristocracy may degenerate into

558:, who read Spinoza, subsequently called the "

536:

373:Chapter 18. The Hebrew state and its history.

711:of Spinoza (George Bell & Sons, London).

690:

500:. God has not elevated one over the other.

418:

1214:and the Jewish Philosophical Tradition" in

1037:, Vol. 3, No. 12 (Oct., 1928), pp. 544–545.

355:Chapter 12. Divine law and the word of God.

1324:

1310:

651:

376:Chapter 19. Sovereign powers and religion.

349:Chapter 10. Remaining Old Testament books.

328:Chapter 3. On the vocation of the Hebrews.

27:

1225:. New Haven: Yale University Press 1997.

1216:Jewish Thought in the Seventeenth Century

826:de Spinoza. Theologisch-politiek traktaat

201:, or head of state, with a member of the

149:should be and concludes that a degree of

1176:. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2023.

492:The treatise rejected the notion of the

383:

334:Chapter 5. On ceremonies and narratives.

301:

237:

86:

1023:

1021:

967:

965:

963:

961:

475:

358:Chapter 13. The teachings of Scripture.

189:The vaunted religious tolerance of the

1531:

1499:

1333:Baruch Spinoza (Benedictus de Spinoza)

973:Pringle-Pattison, Andrew Seth (1911).

1305:

687:" as a homage to Spinoza's treatise.

367:Chapter 16. Foundations of the state.

178:

1487:

1350:Tractatus de Intellectus Emendatione

1018:

958:

801:The full title tagline in Latin is:

619:Monarchy, Aristocracy, and Democracy

254:, when he put it aside to write the

157:and religion works best, such as in

95:had travelled 8 or 10 years between

291:, Spinoza's Dutch translator and a

13:

1358:Principia philosophiae cartesianae

1150:

352:Chapter 11. Apostles and prophets.

14:

1595:

1564:Philosophy of religion literature

1291:, a graduate-level research paper

1236:

1162:. Oxford University Press: 2001.

803:Continens Dissertationes aliquot,

361:Chapter 14. Faith and philosophy.

1510:

1498:

1486:

1034:Journal of Philosophical Studies

683:that he title one of his works "

494:Jews being "God's chosen people"

364:Chapter 15. Theology and reason.

1569:Political philosophy literature

1133:

1122:

1113:

1100:

1087:

1074:

1058:

1040:

933:

234:Writing and publication history

22:Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

1549:Books critical of Christianity

1366:Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

1288:Spinoza as a Prophet of Reason

1265:Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

1212:Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

1141:The Philosophy of F. P. Ramsey

921:Theological-Political Treatise

913:

900:

887:

874:

861:

844:

831:

819:

795:

685:Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

656:It is unlikely that Spinoza's

453:Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

114:Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

1:

1460:Spinoza: Practical Philosophy

1257:Theologico-Political Treatise

1249:Theologico-Political Treatise

1067:Theologico-Political Treatise

1029:The correspondence of Spinoza

948:Theologico-Political Treatise

941:Theologico-Political Treatise

788:

331:Chapter 4. On the divine law.

126:Theologico-Political Treatise

16:Philosophical work by Spinoza

1243:Spinoza and Two Views of God

971:For this section cf. espec.

207:First Stadtholderless period

103:, is redolent of stupidity,

7:

749:

325:Chapter 2. On the prophets.

10:

1600:

1559:Books critical of religion

724:(Clarendon Press, Oxford).

607:, as noted by biographers

537:Spinoza's political theory

182:

1554:Books critical of Judaism

1482:

1444:

1392:

1339:

1210:Pines, Shlomo."Spinoza's

714:1958 by A. G. Wernham in

691:Some English translations

669:Synod of Dordrecht (1673)

419:Scriptural interpretation

379:Chapter 20. A free state.

73:

63:

53:

43:

35:

26:

1174:Spinoza, Life and Legacy

1095:Spinoza, Life and Legacy

908:Spinoza, Life and Legacy

289:Jan Hendriksz Glazemaker

1574:Works by Baruch Spinoza

1015:"Spinoza", pp. 135–174.

986:Encyclopædia Britannica

976:"Spinoza, Baruch"

666:Dutch Reformed Church's

652:Reception and influence

531:ancient state of Israel

503:Spinoza also offered a

455:undertook to show that

337:Chapter 6. On miracles.

322:Chapter 1. On prophecy.

1394:Concepts and interests

1009:The Great Philosophers

522:. It was the ultimate

247:

108:

1108:A Book Forged in Hell

919:Benedict de Spinoza,

895:A Book Forged in Hell

812:John 4,13 is added:

556:Jean-Jacques Rousseau

384:Treatment of religion

302:Structure of the work

241:

195:Dutch Reformed Church

183:Further information:

90:

1272:A Spinoza Chronology

1267:– Full text in Latin

1093:Israel, Jonathan I.

541:Spinoza agreed with

476:Treatment of Judaism

433:political philosophy

1454:Cultural depictions

1374:Tractatus Politicus

1157:Israel, Jonathan I.

882:Book Forged in Hell

869:Book Forged in Hell

782:Tractatus Politicus

743:The Collected Works

721:Tractatus Politicus

716:The Political Works

681:Ludwig Wittgenstein

586:applied mathematics

465:Manasseh ben Israel

283:. Spinoza wrote in

266:, Secretary of the

135:early modern period

23:

1139:Nils-Eric Sahlin,

613:Jonathan I. Israel

600:Political Treatise

511:hatred and Jewish

313:Jonathan I. Israel

248:

179:Historical context

131:Benedictus Spinoza

109:

21:

1526:

1525:

1221:Smith, Steven B.

1011:. Phoenix, 2000,

953:Project Gutenberg

837:Smith, Steven B.

771:Demythologization

605:Tractus Politicus

155:freedom of speech

85:

84:

64:Publication place

1591:

1517:Wikisource texts

1514:

1502:

1501:

1490:

1489:

1326:

1319:

1312:

1303:

1302:

1144:

1137:

1131:

1126:

1120:

1117:

1111:

1104:

1098:

1091:

1085:

1080:Nadler, Steven.

1078:

1072:

1062:

1056:

1044:

1038:

1025:

1016:

990:

978:

969:

956:

937:

931:

917:

911:

904:

898:

893:Nadler, Steven,

891:

885:

878:

872:

865:

859:

848:

842:

835:

829:

823:

817:

799:

766:Abraham ibn Ezra

761:Moses Maimonides

596:moral philosophy

281:Henricus Künraht

216:Adriaan Koerbagh

185:Dutch Golden Age

55:Publication date

31:

24:

20:

1599:

1598:

1594:

1593:

1592:

1590:

1589:

1588:

1544:Anonymous works

1529:

1528:

1527:

1522:

1478:

1440:

1388:

1335:

1330:

1239:

1153:

1151:Further reading

1148:

1147:

1143:(1990), p. 227.

1138:

1134:

1127:

1123:

1118:

1114:

1105:

1101:

1092:

1088:

1082:Spinoza, A Life

1079:

1075:

1063:

1059:

1045:

1041:

1026:

1019:

993:Antonio Damasio

970:

959:

938:

934:

918:

914:

905:

901:

892:

888:

879:

875:

866:

862:

849:

845:

836:

832:

824:

820:

800:

796:

791:

752:

736:Jonathan Israel

709:The Chief Works

693:

673:Jakob Thomasius

654:

621:

581:

539:

524:anthropological

478:

421:

386:

304:

264:Henry Oldenburg

236:

203:House of Orange

187:

181:

107:forgive me...".

78:

56:

17:

12:

11:

5:

1597:

1587:

1586:

1584:Censored books

1581:

1576:

1571:

1566:

1561:

1556:

1551:

1546:

1541:

1524:

1523:

1521:

1520:

1508:

1496:

1483:

1480:

1479:

1477:

1476:

1471:

1463:

1456:

1450:

1448:

1442:

1441:

1439:

1438:

1433:

1428:

1423:

1416:

1411:

1404:

1398:

1396:

1390:

1389:

1387:

1386:

1378:

1370:

1362:

1354:

1345:

1343:

1337:

1336:

1329:

1328:

1321:

1314:

1306:

1300:

1299:

1297:

1292:

1284:

1279:

1274:

1269:

1261:

1253:

1245:

1238:

1237:External links

1235:

1234:

1233:

1219:

1208:

1194:Nadler, Steven

1191:

1184:

1170:

1152:

1149:

1146:

1145:

1132:

1121:

1112:

1099:

1086:

1073:

1057:

1039:

1017:

1001:Richard McKeon

981:Chisholm, Hugh

957:

932:

912:

899:

886:

873:

860:

852:Nadler, Steven

843:

830:

818:

793:

792:

790:

787:

786:

785:

778:

773:

768:

763:

758:

751:

748:

747:

746:

739:

732:

729:Complete Works

725:

712:

705:

692:

689:

653:

650:

620:

617:

580:

577:

538:

535:

477:

474:

437:interpretation

420:

417:

385:

382:

381:

380:

377:

374:

371:

368:

365:

362:

359:

356:

353:

350:

347:

344:

341:

338:

335:

332:

329:

326:

323:

320:

303:

300:

244:Baruch Spinoza

235:

232:

191:Dutch Republic

180:

177:

173:Dutch Republic

83:

82:

79:

74:

71:

70:

68:Dutch Republic

65:

61:

60:

57:

54:

51:

50:

45:

41:

40:

39:Baruch Spinoza

37:

33:

32:

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1596:

1585:

1582:

1580:

1577:

1575:

1572:

1570:

1567:

1565:

1562:

1560:

1557:

1555:

1552:

1550:

1547:

1545:

1542:

1540:

1537:

1536:

1534:

1519:

1518:

1513:

1509:

1507:

1506:

1497:

1495:

1494:

1485:

1484:

1481:

1475:

1474:Spinoza Prize

1472:

1469:

1468:

1467:New Jerusalem

1464:

1462:

1461:

1457:

1455:

1452:

1451:

1449:

1447:

1443:

1437:

1434:

1432:

1429:

1427:

1424:

1422:

1421:

1417:

1415:

1412:

1410:

1409:

1405:

1403:

1400:

1399:

1397:

1395:

1391:

1384:

1383:

1379:

1376:

1375:

1371:

1368:

1367:

1363:

1360:

1359:

1355:

1352:

1351:

1347:

1346:

1344:

1342:

1338:

1334:

1327:

1322:

1320:

1315:

1313:

1308:

1307:

1304:

1298:

1296:

1293:

1290:

1289:

1285:

1283:

1280:

1278:

1275:

1273:

1270:

1268:

1266:

1262:

1259:

1258:

1254:

1251:

1250:

1246:

1244:

1241:

1240:

1232:

1231:0-300-06680-5

1228:

1224:

1220:

1217:

1213:

1209:

1207:

1206:9780691139890

1203:

1199:

1195:

1192:

1189:

1185:

1183:

1182:9780198857488

1179:

1175:

1171:

1169:

1168:0-19-925456-7

1165:

1161:

1158:

1155:

1154:

1142:

1136:

1130:

1125:

1116:

1109:

1103:

1096:

1090:

1083:

1077:

1070:

1068:

1061:

1055:

1053:

1048:

1047:Thomas Hobbes

1043:

1036:

1035:

1030:

1024:

1022:

1014:

1010:

1006:

1002:

998:

994:

988:

987:

982:

977:

968:

966:

964:

962:

954:

950:

949:

944:

942:

936:

930:

929:9780521530972

926:

922:

916:

909:

903:

896:

890:

883:

877:

870:

864:

857:

853:

847:

840:

834:

827:

822:

815:

810:

807:

804:

798:

794:

784:

783:

779:

777:

774:

772:

769:

767:

764:

762:

759:

757:

756:Thomas Hobbes

754:

753:

744:

740:

737:

733:

730:

726:

723:

722:

717:

713:

710:

706:

703:

699:

698:Robert Willis

695:

694:

688:

686:

682:

679:suggested to

678:

674:

670:

667:

663:

662:Johan de Witt

659:

649:

646:

642:

638:

634:

630:

626:

616:

614:

610:

609:Steven Nadler

606:

601:

597:

593:

592:

587:

576:

573:

569:

563:

561:

557:

553:

549:

544:

543:Thomas Hobbes

534:

532:

527:

525:

521:

516:

514:

510:

506:

501:

499:

495:

490:

487:

483:

473:

470:

466:

462:

458:

454:

449:

446:

442:

438:

434:

430:

426:

416:

414:

413:

407:

403:

398:

396:

392:

378:

375:

372:

369:

366:

363:

360:

357:

354:

351:

348:

345:

342:

339:

336:

333:

330:

327:

324:

321:

318:

317:

316:

314:

310:

299:

297:

294:

290:

286:

282:

276:

273:

269:

268:Royal Society

265:

261:

257:

253:

245:

240:

231:

229:

225:

221:

217:

212:

211:Johan de Witt

208:

205:. During the

204:

200:

196:

192:

186:

176:

174:

170:

169:

164:

160:

156:

152:

148:

144:

140:

136:

132:

128:

127:

122:

121:

116:

115:

106:

102:

98:

94:

89:

80:

77:

76:Dewey Decimal

72:

69:

66:

62:

58:

52:

49:

46:

42:

38:

34:

30:

25:

19:

1516:

1504:

1492:

1465:

1458:

1418:

1406:

1380:

1372:

1365:

1364:

1356:

1348:

1287:

1264:

1256:

1248:

1222:

1215:

1211:

1197:

1187:

1173:

1159:

1140:

1135:

1124:

1115:

1107:

1102:

1094:

1089:

1081:

1076:

1066:

1060:

1051:

1042:

1033:

1028:

1012:

1008:

1004:

996:

984:

947:

940:

935:

920:

915:

907:

902:

894:

889:

881:

876:

868:

863:

855:

846:

838:

833:

825:

821:

813:

808:

805:

802:

797:

780:

742:

728:

719:

715:

708:

657:

655:

622:

604:

599:

589:

582:

564:

560:general will

552:commonwealth

540:

528:

520:circumcision

517:

505:sociological

502:

491:

485:

479:

452:

450:

422:

411:

399:

387:

308:

305:

277:

271:

259:

255:

251:

249:

242:Portrait of

223:

219:

209:(1650–1672)

188:

166:

125:

124:

119:

118:

113:

112:

110:

18:

1470:(2008 play)

1446:Works about

1431:Determinism

1377:(1675–1676)

945:; cf. also

677:G. E. Moore

629:aristocracy

591:Realpolitik

461:John Bunyan

425:metaphysics

410:purpose or

296:freethinker

97:Mesopotamia

1539:1670 books

1533:Categories

1436:Secularism

850:quoted in

789:References

776:Toleration

702:Wikisource

575:churches.

572:pantheists

513:separatism

498:liberalism

395:prejudices

311:edited by

293:Collegiant

199:stadholder

1579:Treatises

1505:Wikiquote

1426:Pantheism

1420:Causa sui

1414:Multitude

1402:Immanence

1052:Leviathan

658:Tractatus

645:oligarchy

641:autocracy

633:democracy

457:Scripture

391:Scripture

285:Neo-Latin

159:Amsterdam

151:democracy

1341:Works by

1172:______.

1106:Nadler,

1069:, Ch. 20

943:, Ch. 12

910:, 955–57

906:Israel,

880:Nadler,

867:Nadler,

750:See also

734:2007 by

696:1862 by

625:monarchy

406:miracles

402:prophecy

319:Preface.

228:Apologia

163:politics

147:religion

81:199/.492

44:Language

1493:Commons

1408:Conatus

983:(ed.).

884:, 38-45

637:tyranny

509:Gentile

482:yeshiva

246:, 1665.

1385:(1677)

1382:Ethics

1369:(1670)

1361:(1663)

1353:(1662)

1229:

1204:

1180:

1166:

955:eText.

927:

631:, and

568:deists

469:Nature

252:Ethics

168:Ethics

101:Bethel

36:Author

1110:, 230

979:. In

548:state

445:Torah

441:Moses

429:moral

412:telos

143:state

139:Bible

123:) or

93:Jacob

48:Latin

1227:ISBN

1202:ISBN

1178:ISBN

1164:ISBN

1064:Cf.

1027:Cf.

1013:s.v.

925:ISBN

871:, xi

611:and

451:His

431:and

427:and

404:and

153:and

145:and

111:The

105:Ezra

99:and

59:1670

562:".

550:or

486:TTP

309:TTP

272:TTP

260:TTP

256:TTP

224:TTP

220:TTP

120:TTP

1535::

1196:.

1049:,

1020:^

1003:,

995:,

960:^

951:,

854:,

627:,

615:.

570:,

515:.

463:,

315:.

1325:e

1318:t

1311:v

1071:.

704:.

117:(

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.