17:

319:

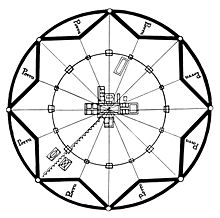

located. The town contained three squares – one for the prince’s palace, one for the cathedral, and one for the market. Because the

Renaissance was much taken with the idea of the canal town, in Filarete's Sforzinda every other street had a canal for cargo transport. The canal system also connected with the river, and thus the outside world, for the import and export of goods. The city also contained many buildings, including parishes and separate schools for boys and girls. An example of a building that appears in the treatise is Filarete’s House of Vice and Virtue, a ten-storey structure with a brothel on the bottom and an academy of learning on the higher levels. Filarete did much study on representation of Vices and Virtues, and there are suggestions that his radial design for the city was inspired by

137:

190:

201:

181:, which were completed in 1445. Although they were created during the Renaissance, the doors have distinct Byzantine influences and seem tied to the Medieval era. Some critics have noted that the doors offer a glimpse into the mind of Filarete, claiming that they show his “mind of medieval complexity crammed full of exciting but not quite assimilated classical learning”.

315:

drawings and even more his allegorical drawings traced on the margins of the Codex

Magliabechianus – such as the Allegory of Vertue and the Allegory of the Reason and Will – Filarete shows a remarkable possession of classical sources, maybe known also through the advice of his friend Francesco Filelfo da Tolentino, the main humanist then at the court of Milan.

335:. Filarete’s ideal plan was meant to reflect on society – where a perfect city form would be the image of a perfect society, an idea that was typical of the humanist views prevalent during the High Renaissance. The Renaissance ideal city implied the centralized power of a prince in its organization, an idea following closely on the heels of

363:

Although it was never built, Sforzinda served as an inspiration for many future city plans. For example, in the 16th century, Renaissance military engineers and architects combined

Filarete's ideal city schemes with defensive fortifications deriving from a more sociopolitical agenda. This notion of

309:

The basic layout of the city is an eight-point star, created by overlaying two squares so that all the corners were equidistant. This shape is then inscribed within a perfect circular moat. This shape is iconographic and probably ties to

Filarete’s interest in magic and astrology. Consistent with

347:

Filarete's plan of

Sforzinda was the first ideal city plan of the Renaissance and his thorough organization of its layout embodied a greater level of conscious city planning than anyone before him. Despite the many references to medieval symbolism incorporated into Sforzinda's design, the city's

318:

In terms of planning, each of the outer points of the star had towers, while the inner angles had gates. Each of the gates was an outlet of radial avenues that each passed through a market square, dedicated to certain goods. All the avenues finally converged in a large square which was centrally

326:

The design of

Sforzinda may have been in part a direct response to the Italian cities of the Medieval period, whose growth did not necessarily depend on city planning as such, which meant they could be difficult to navigate. In part, the Renaissance humanist interest in classical texts may have

314:

or fifteenth century notions concerning the talismanic power of geometry and the crucial importance of astrology, Filarete provides, in addition to pragmatic advice on materials, construction, and fortifications, notes on how to propitiate celestial harmony within

Sforzinda. His architectonical

671:

Andreas Beyer: "Künstlerfreunde – Künstlerfeinde. Anmerkungen zu einem Topos der Künstler- und

Kunstgeschichte", (on Filarete's Portal in St Peter's in Rome), in Andreas Beyer: Die Kunst – zur Sprache gebracht, Verlag Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin 2017, pp. 64–82.

289:

The book, which is written as a fictional narrative, consists principally of a detailed account of the technical aspects of architecture (e.g., site and material selection, drawing, construction methods, and so on) and a sustained polemic against the

215:(c. 1456), the overall form of which was rationally planned as a cross within a square, with the hospital church at the center of the plan. Some of the surviving sections of the much-rebuilt structure show the Gothic detail of Milan's

339:’s that “The human race is at its best under a monarch.” Thus it could be argued that the Renaissance ideal city form was tensioned between the perceived need for a centralized power and the potential reality of tyranny.

659:"Il Filarete." International Dictionary of Architects and Architecture. St. James Press, 1993. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Gale, 2009.

348:

principles became the archetype for the humanist city during the High

Renaissance. The treatise gained interest from many important leaders such as Giangaleazzo Sforza and

259:, which comprises twenty-five volumes, enjoyed a fairly wide circulation in manuscript form during the Renaissance. The most well known and best preserved copy of the

415:

preceded this. In the following century, Filarete's doors were preserved when Old St Peter's was demolished and they were later reinstalled in the new

695:

639:

486:

124:. There he became a ducal engineer and worked on a variety of architectural projects for the next fifteen years. According to his biographer,

16:

603:

599:

Originally composed in Milan c. 1460 – c. 1464. Translated by John R. Spencer. Facsimile ed. 2 vols. New Haven: Yale

University Press, 1965.

610:

104:

where he probably trained as a craftsman. Sources suggest that he worked in Florence under the Italian painter, architect, and biographer

733:

644:

500:

Coen, P. (2000). "Il problema della Ragione e della Volontà: il contributo di un'allegoria di Antonio Averlino, detto il Filarete".

108:, who gave him his more famous name “Filarete” which means “a lover of virtue”. In the mid 15th century, Filarete was expelled from

743:

738:

621:

153:

306:, then Duke of Milan. Although Sforzinda was never built, certain aspects of its design are described in considerable detail.

728:

677:

412:

286:

and was conserved in Florence suggests that Filarete was well regarded in his native Florence despite his loyalty to Milan.

723:

718:

634:

758:

471:

Coen, P. (1994). "La allegoria della Virtù di Antonio Averlino, detto il Filarete". In Rossi, S.; Valeri, S. (eds.).

136:

665:

Kostof, Spiro. The City Assembled: The Elements of Urban Form Through History. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. 1991.

753:

349:

294:

of Northern Italy, which Filarete calls the "barbarous modern style." Filarete argues instead for the use of

283:

323:’s Earthly City, whose circular shape was divided into sections, each of which had its own Vice and Virtue.

247:

Filarete completed his substantial book on architecture sometime around 1464, which he referred to as his

174:

597:

Filarete's Treatise on Architecture: Being the Treatise by Antonio di Piero Averlino, Known as Filarete.

748:

650:

563:

St. James Press, 1993. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Gale, 2009.

384:

St. James Press, 1993. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Gale, 2009.

364:

combining the ideal and the fortified city became widely disseminated throughout Europe and beyond.

685:

Madanipour, Ali. Designing the City of Reason: Foundation and Frameworks. New York: Routledge, 2007

660:

564:

385:

242:

668:

Kostof, Spiro. The City Shaped: Urban Patterns and Meanings. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. 1991.

416:

295:

88:, and architectural theorist. He is perhaps best remembered for his design of the ideal city of

74:

66:

768:

763:

251:("Architectonic book"). Neither he nor his immediate contemporaries ever referred to it as a

149:

682:

Lang, S. The Ideal City from Plato to Howard. Architectural Review 112. Aug. 1952, pp 95–96

353:

8:

291:

480:

320:

226:

236:

673:

357:

212:

303:

113:

105:

61:

34:

230:

166:

712:

614:

193:

141:

327:

stimulated preoccupations with geometry in city layouts, as for example, in

217:

688:

Roeder, Helen. “The Borders of Filarete's Bronze Doors to St. Peters”.

590:

The City in History: Its Origins and Transformations, and its Prospects

428:

Roeder, Helen. 'The Borders of Filarete's Bronze Doors to St. Peters'.

299:

298:

models. The most famous part of his book is his plan for Sforzinda, an

205:

145:

89:

85:

81:

77:

360:

began to plan their ideal cities they borrowed ideas from Filarete.

189:

332:

237:

Filarete's treatise on architecture and the ideal city of Sforzinda

101:

273:

661:

http://0-galenet.galegroup.com.ilsprod.lib.neu.edu/servlet/BioRC

565:

http://0-galenet.galegroup.com.ilsprod.lib.neu.edu/servlet/BioRC

386:

http://0-galenet.galegroup.com.ilsprod.lib.neu.edu/servlet/BioRC

700:: Claiming Authorship and Status on the Doors of St. Peter's."

515:

Lang, S. (August 1952). "The ideal city from Plato to Howard".

401:. Vol. VII. London: Spink & Son Ltd. pp. 302–304.

170:

169:

meant that Filarete, over the course of twelve years, cast the

125:

117:

336:

328:

200:

121:

221:

craft traditions, which are at odds with Filarete's design

178:

160:

109:

342:

561:

International Dictionary of Architects and Architecture.

382:

International Dictionary of Architects and Architecture.

255:("Treatise"), though it is usually now called such. The

532:

Designing the City of Reason: Foundation and frameworks

112:

after being accused of attempting to steal the head of

225:

or "after the Antique". Filarete also worked on the

640:

Fred Luminoso, 2000. "The Ideal City: Then and Now"

263:is a profusely illustrated manuscript known as the

710:

92:, the first ideal city plan of the Renaissance.

690:Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes

430:Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes

148:'s medal marking the 1439 visit to Florence of

100:Antonio di Pietro Averlino was born c. 1400 in

451:

449:

447:

544:

458:The City Shaped: Urban patterns and meanings

629:The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance

529:

485:: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (

444:

274:"Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze"

35:[anˈtɔːnjodiˈpjɛːtroaver(u)ˈliːno]

23:Italian architect and sculptor (1400–1469)

396:

592:. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

199:

188:

161:Bronze doors of Old St. Peter's Basilica

135:

73:, meaning "lover of excellence"), was a

15:

656:Alighieri, Dante. De Monarchia. c. 1312

613:on Filarete and da Vinci's theories of

711:

455:

411:Ghiberti's great bronze doors for the

343:Influence on architecture and urbanism

271:1465; now held in the archives of the

184:

645:"Sforzinda: progetto di città ideale"

399:Biographical Dictionary of Medallists

60:

33:

692:, Vol. 10, (1947), pp. 150–153.

514:

499:

470:

13:

14:

780:

128:, Filarete died in Rome c. 1469.

734:Italian male non-fiction writers

519:. Vol. 112. pp. 95–96.

460:. London, UK: Thames and Hudson.

744:15th-century Italian architects

569:

553:

538:

523:

432:, Vol. 10, (1947), pp. 150–153.

739:Italian Renaissance architects

508:

493:

464:

435:

422:

405:

390:

374:

1:

631:(London: Batsford), pp 100ff.

582:

268:

46:

39:

27:Antonio di Pietro Aver(u)lino

729:Italian architecture writers

545:Alighieri, Dante (c. 1312).

473:Le due Rome del Quattrocento

397:L. Forrer, Filarete (1923).

229:or Sforza Castle and on the

211:In Milan Filarete built the

95:

7:

724:Italian Renaissance writers

719:Architectural theoreticians

696:Glass, Robert. "Filarete's

10:

785:

534:. New York, NY: Routledge.

240:

70:

704:94, no. 4 (2012): 548–71.

759:Architects from Florence

653:at stpetersbasilica.info

530:Madanipour, Ali (2007).

367:

243:Trattato di architettura

175:Old St. Peter's Basilica

165:A commission granted by

131:

627:Peter J. Murray, 1963.

120:and then eventually to

754:Italian male sculptors

588:Mumford, Lewis. 1961.

456:Kostof, Spiro (1991).

413:Baptistery of Florence

208:

197:

157:

75:Florentine Renaissance

31:Italian pronunciation:

20:

278:). The fact that the

203:

192:

150:John VIII Palaiologos

139:

19:

517:Architectural Review

417:St. Peter's Basilica

354:Francesco di Giorgio

280:Codex Magliabechiano

265:Codex Magliabechiano

249:Libro architettonico

233:or Milan Cathedral.

62:[filaˈrɛːte]

624:of the center door.

185:Architectural works

595:Filarete, (1965).

331:'s description of

267:(probably drafted

227:Castello Sforzesco

209:

198:

173:central doors for

158:

140:Copy by Filarete (

21:

749:Italian sculptors

678:978-3-8031-2784-6

651:The Filarete Door

635:Plan of Sforzinda

617:and architecture.

358:Leonardo da Vinci

213:Ospedale Maggiore

154:Byzantine Emperor

776:

702:The Art Bulletin

576:

573:

567:

557:

551:

550:

542:

536:

535:

527:

521:

520:

512:

506:

505:

497:

491:

490:

484:

476:

468:

462:

461:

453:

442:

439:

433:

426:

420:

409:

403:

402:

394:

388:

378:

350:Piero de' Medici

304:Francesco Sforza

284:Piero de' Medici

282:is dedicated to

277:

270:

116:and he moved to

114:John the Baptist

106:Lorenzo Ghiberti

72:

64:

59:

51:

48:

44:

41:

37:

32:

784:

783:

779:

778:

777:

775:

774:

773:

709:

708:

585:

580:

579:

574:

570:

559:"Il Filarete."

558:

554:

543:

539:

528:

524:

513:

509:

498:

494:

478:

477:

469:

465:

454:

445:

440:

436:

427:

423:

410:

406:

395:

391:

380:'Il Filarete.'

379:

375:

370:

352:and later when

345:

296:classical Roman

272:

245:

239:

231:Duomo di Milano

187:

163:

134:

98:

57:

49:

42:

30:

24:

12:

11:

5:

782:

772:

771:

766:

761:

756:

751:

746:

741:

736:

731:

726:

721:

707:

706:

693:

686:

683:

680:

669:

666:

663:

657:

654:

648:

642:

637:

632:

625:

618:

607:

600:

593:

584:

581:

578:

577:

568:

552:

537:

522:

507:

492:

463:

443:

434:

421:

404:

389:

372:

371:

369:

366:

344:

341:

241:Main article:

238:

235:

186:

183:

167:Pope Eugene IV

162:

159:

156:, 1425 to 1448

133:

130:

97:

94:

22:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

781:

770:

767:

765:

762:

760:

757:

755:

752:

750:

747:

745:

742:

740:

737:

735:

732:

730:

727:

725:

722:

720:

717:

716:

714:

705:

703:

699:

694:

691:

687:

684:

681:

679:

675:

670:

667:

664:

662:

658:

655:

652:

649:

646:

643:

641:

638:

636:

633:

630:

626:

623:

619:

616:

615:city planning

612:

608:

605:

601:

598:

594:

591:

587:

586:

575:Kostof, 1991.

572:

566:

562:

556:

548:

541:

533:

526:

518:

511:

503:

502:Arte Lombarda

496:

488:

482:

474:

467:

459:

452:

450:

448:

438:

431:

425:

418:

414:

408:

400:

393:

387:

383:

377:

373:

365:

361:

359:

355:

351:

340:

338:

334:

330:

324:

322:

321:St. Augustine

316:

313:

307:

305:

301:

297:

293:

287:

285:

281:

275:

266:

262:

258:

254:

250:

244:

234:

232:

228:

224:

220:

219:

214:

207:

202:

195:

194:Sforza Castle

191:

182:

180:

176:

172:

168:

155:

151:

147:

143:

138:

129:

127:

123:

119:

115:

111:

107:

103:

93:

91:

87:

83:

79:

76:

68:

67:Ancient Greek

63:

55:

36:

28:

18:

769:1460s deaths

764:1400s births

701:

697:

689:

647:(in Italian)

628:

596:

589:

571:

560:

555:

547:De Monarchia

546:

540:

531:

525:

516:

510:

501:

495:

472:

466:

457:

441:Murray 1963.

437:

429:

424:

407:

398:

392:

381:

376:

362:

346:

325:

317:

312:Quattrocento

311:

308:

302:named after

292:Gothic style

288:

279:

264:

260:

256:

252:

248:

246:

222:

218:Quattrocento

216:

210:

164:

99:

53:

52:), known as

26:

25:

622:description

475:. Rome, IT.

142:Electrotype

50: 1469

43: 1400

713:Categories

583:References

300:ideal city

223:all'antica

698:Hilaritas

604:biography

481:cite book

206:Sforzinda

146:Pisanello

96:Biography

90:Sforzinda

86:medallist

78:architect

71:φιλάρετος

602:A short

333:Atlantis

253:Trattato

204:Plan of

196:in Milan

102:Florence

82:sculptor

58:Italian:

54:Filarete

65:; from

676:

171:bronze

126:Vasari

118:Venice

611:essay

368:Notes

337:Dante

329:Plato

261:Libro

257:Libro

144:) of

132:Works

122:Milan

674:ISBN

487:link

356:and

179:Rome

110:Rome

609:An

177:in

715::

620:A

483:}}

479:{{

446:^

269:c.

152:,

84:,

80:,

69::

47:c.

45:–

40:c.

38:;

606:.

549:.

504:.

489:)

419:.

276:.

56:(

29:(

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.