151:, and creep. Suspended grains are fine granules that can easily be picked up by wind and carried for variable distances. Most visitors to coastal beach environments can attest to having sand blown in their face or leaving with a gritty feeling on their skin. This is due to fine sediment suspended in the moisture rich air. When suspended sediment is returned to the ground, granules physically impact the grounded grains. Due to physics principles, the grounded grains are receiving energy from the once suspended sediment. This impact leads to the dislodgement of grounded grains or creep of coarser grains. Saltation is the movement of grains being picked up by the wind and dropped in a cycling repetitive motion.

237:, dune mat vegetation was relatively abundant and thriving. This data shows that with active restoration efforts to combat invasive species, land managers could sustain a healthy native vegetation population and thus transform the landscape back to its native habitat. Understanding how invasive species change and manipulate landscapes and the characteristics of specific invasive species, is the best way to reduce impacts and restore ecosystems for native species.

82:

117:

are identified by vegetated dune ridges and vegetated deflated plains. Due to variable wind gusts, parabolic dunes are commonly unvegetated in troughs or dune swells where wind tunnels transport currents. Ripple alignment in association with the main dunes can also identify parabolic dunes. Ripples

163:

Sediment accumulation can also be a result of wave action. Wave currents occur in a swash and backwash motion. This continual wave action allows for the movement of sediment. The angles at which the swash and backwash occur, are associated with the off shore transport current as well as the change

159:

Coastal environments act as drainage outlets for freshwater river systems. As a result, sediment from tributaries and headwaters are deposited at the mouth of the river. Long shore transport is a linear current off the coastline that moves sediment. For

Northern California, this current moves

130:

Northern

California coastal dune environments are subject to high velocity winds at all times throughout the year. This strong variable causes the morphology of the dune ecosystem to constantly change. Dunes can range in height from a meter to tens of meters tall creating elevation changes and

93:

begins with the first dune ridge directly behind an active beach. The ridge of a foredune can range in height from a few meters to tens of meters tall. Foredunes are formed when sand accumulates and wind actively transforms the landscape. This results in

66:

that form in the wind shadows of clumps of vegetation. Several shadow dunes may eventually join to form an incipient foredune. When an incipient foredune reaches a height of about 1.5 feet (0.5 m), it has a significant wind shadow of its own.

172:

The vegetation analyzed at the Mad River County Beach showed an evolutionary change in the ecosystem as a result of several thriving invasive species. Upon arrival to the beach, it became visually apparent just how abundant the

262:

begins to accumulate massive amounts of sand creating large foredune ridges. The alteration of dune morphology affects native plants and animal species that rely heavily on the dunes for nourishment and habitat.

190:

attaches and begins to grow on a relatively flat dune system, wind currents that push sand inland it allows the plant to accumulate and mound massive amounts of sand creating large foredune ridges.

71:

will tend to fall on this incipient dune rather than traveling further inland. When a foredune becomes 3 to 5 feet (0.9 to 1.5 m) high, it may trap all of the wind-blown sand from the beach.

214:

entering an ecosystem, are elevated levels of nitrogen within the soil . Unfortunately, the implementation of nitrogen into the soil, limits the growth and livelihood of other species such as

206:(ripgut brome). Since introduction of these invasive plants, scientists have recorded a severe displacement in native grasses and dune mat vegetation throughout California. A characteristic of

160:

sediment in a northern direction. Therefore, sand and sediment constructing

Humboldt Bay's thirty-four mile dune ecosystem, is a result of sediment deposition at a southern location.

122:, the wind is predominately blowing in from the northwest. As a result, the dune ridges are formed parallel to the wind currents while ripples are formed perpendicular to the wind.

233:

has been introduced into the

California landscape to perform as a natural re-engineering feature to transform the beach landscape. In areas without

506:

118:

minuet accumulations of sand against the main dune swale. The heights of ripples are normally measured on a millimeter to centimeter scale. In

243:

is an ecosystem engineer that has the ability to displace native dune mat vegetation by transforming historical dune ecology. Removal of

258:

invades the historically flat

Californian foredunes transforming the ecology of the dune system. As wind currents push sand inland, the

74:

In active dune systems, the foredunes appear closest to the sea or other body of water. However, some dune systems, such as those on

99:

251:

has evolved to grow in“vigorous root and rhizome systems”. Research shows that these root systems can be in excess of ten feet.

284:

135:

can further armor dune ridges, creating linear dunes, and preventing naturalistic parabolic dunes from being created.

383:

361:

339:

526:

17:

455:

78:

coasts, do not have foredunes. In those systems, other kinds of dunes may be closest to the water.

106:. Active sand sheets at Lanphere Dunes have been measured to be in excess of six hundred meters.

144:

46:

deposited by wind on a vegetated part of the shore. Foredunes can be classified generally as

299:

8:

148:

303:

500:

449:

222:

179:

175:

311:

196:

68:

307:

132:

202:

531:

103:

315:

520:

216:

119:

95:

427:

Chapter 10: Wind as a

Geomorphic Agent: Key Concepts in Geomorphology

90:

490:

247:

presents a daunting task for land managers and restoration teams.

493:

Invasive Weeds of

Humboldt County: A Guide for Concerned Citizens

75:

39:

38:

ridge that runs parallel to the shore of an ocean, lake, bay, or

285:"Foredunes and blowouts: initiation, geomorphology and dynamics"

193:

This shift is supporting the invasion of but not limited to,

81:

27:

Dune ridge that runs parallel to the shore of a body of water

478:

Ecology and

Restoration of Northern California Coastal Dunes

114:

43:

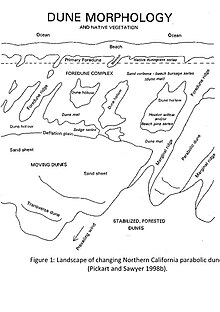

35:

429:. W. H. Freeman and Company Publishers. pp. 329–354.

109:

439:

405:

403:

401:

182:

species is. According to

Pickart and Sawyer (1998),

471:

469:

467:

465:

414:. California Native Plant Society. pp. 41–55.

480:. California Native Plant Society. pp. 1–36.

424:

398:

85:Landscape of Northern California parabolic dunes.

518:

462:

384:"Lake Michigan Coastal Dunes: Active Foredunes"

491:Humboldt County Weed Management Area (2010).

475:

409:

186:is described as being foredune engineers. As

143:Sand granules are transported in three ways:

340:"Lake Michigan Coastal Dunes: Shadow Dunes"

505:: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (

362:"Lake Michigan Coastal Dunes: Foredunes"

80:

425:Bierman, P.; Montgomery, D. R. (2014).

100:United States Fish and Wildlife Service

14:

519:

278:

276:

154:

110:Parabolic dunes in Northern California

164:in winter and summer ocean currents.

138:

282:

273:

167:

24:

98:can consuming in-land ecosystems.

25:

543:

476:Pickart, A.; Sawyer, J. (1998).

410:Pickart, A.; Sawyer, J. (1998).

102:actively manages Humboldt Bay's

484:

433:

418:

376:

354:

332:

13:

1:

440:Friends of the Dunes (n.d.).

312:10.1016/S0169-555X(02)00184-8

266:

57:

7:

10:

548:

442:Coastal Naturalist Manual

444:. Friends of the Dunes.

229:Since the early 1900s,

125:

62:Foredunes may begin as

42:. Foredunes consist of

412:Invasive Plant Species

283:Hesp, Patrick (2002).

180:(European beach grass)

131:habitat complexities.

86:

495:. Arcata, California.

84:

454:: CS1 maint: year (

254:Characteristically,

195:Ammophila arenaria,

304:2002Geomo..48..245H

155:Sources of sediment

260:Ammophila arenaria

256:Ammophila arenaria

249:Ammophila arenaria

245:Ammophila arenaria

241:Ammophila arenaria

235:Ammophila arenaria

231:Ammophila arenaria

223:Erysimum menziesii

208:Ammophila arenaria

188:Ammophila arenaria

184:Ammophila arenaria

176:Ammophila arenaria

139:Sediment transport

87:

527:Coastal geography

197:Tanacetum vulgare

16:(Redirected from

539:

511:

510:

504:

496:

488:

482:

481:

473:

460:

459:

453:

445:

437:

431:

430:

422:

416:

415:

407:

396:

395:

393:

391:

386:. Calvin College

380:

374:

373:

371:

369:

364:. Calvin College

358:

352:

351:

349:

347:

342:. Calvin College

336:

330:

329:

327:

326:

320:

314:. Archived from

298:(1–3): 245–268.

289:

280:

168:Foredune ecology

133:Invasive species

21:

547:

546:

542:

541:

540:

538:

537:

536:

517:

516:

515:

514:

498:

497:

489:

485:

474:

463:

447:

446:

438:

434:

423:

419:

408:

399:

389:

387:

382:

381:

377:

367:

365:

360:

359:

355:

345:

343:

338:

337:

333:

324:

322:

318:

287:

281:

274:

269:

212:Bromus diandrus

203:Bromus diandrus

170:

157:

141:

128:

115:Parabolic dunes

112:

69:Wind-blown sand

60:

28:

23:

22:

15:

12:

11:

5:

545:

535:

534:

529:

513:

512:

483:

461:

432:

417:

397:

375:

353:

331:

271:

270:

268:

265:

169:

166:

156:

153:

140:

137:

127:

124:

111:

108:

104:Lanphere Dunes

59:

56:

26:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

544:

533:

530:

528:

525:

524:

522:

508:

502:

494:

487:

479:

472:

470:

468:

466:

457:

451:

443:

436:

428:

421:

413:

406:

404:

402:

385:

379:

363:

357:

341:

335:

321:on 2010-06-25

317:

313:

309:

305:

301:

297:

293:

292:Geomorphology

286:

279:

277:

272:

264:

261:

257:

252:

250:

246:

242:

238:

236:

232:

227:

225:

224:

219:

218:

217:Layia carnosa

213:

209:

205:

204:

199:

198:

191:

189:

185:

181:

178:

177:

165:

161:

152:

150:

146:

136:

134:

123:

121:

116:

107:

105:

101:

97:

92:

83:

79:

77:

72:

70:

65:

55:

53:

49:

45:

41:

37:

33:

19:

492:

486:

477:

441:

435:

426:

420:

411:

390:December 10,

388:. Retrieved

378:

368:December 10,

366:. Retrieved

356:

346:December 10,

344:. Retrieved

334:

323:. Retrieved

316:the original

295:

291:

259:

255:

253:

248:

244:

240:

239:

234:

230:

228:

221:

215:

211:

207:

201:

200:(tansy) and

194:

192:

187:

183:

174:

171:

162:

158:

142:

129:

120:Humboldt Bay

113:

88:

73:

64:shadow dunes

63:

61:

51:

47:

31:

29:

96:sand sheets

89:A foredune

52:established

521:Categories

325:2012-12-11

267:References

145:suspension

501:cite book

450:cite book

149:saltation

91:ecosystem

58:Formation

48:incipient

18:Foredunes

32:foredune

300:Bibcode

76:eroding

40:estuary

34:is a

532:Dunes

319:(PDF)

288:(PDF)

507:link

456:link

392:2012

370:2012

348:2012

220:and

210:and

126:Wind

44:sand

36:dune

308:doi

50:or

523::

503:}}

499:{{

464:^

452:}}

448:{{

400:^

306:.

296:48

294:.

290:.

275:^

226:.

147:,

54:.

30:A

509:)

458:)

394:.

372:.

350:.

328:.

310::

302::

20:)

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.