461:

473:

485:

189:

going through the perforations. Clay was impressed on the cord to avoid unauthorized reading and the bottom of the document was then wrapped around the initial scroll. Bullae found in dig sites that appear concave and smooth and unmarked are thus these initial molds of clay placed around the interior scroll. A new cord was introduced around the document and a bullae attached to the ends of the cord, on the knot of the cord, or around the cord in its entirety, forming a ring. These outer rings could not guarantee unauthorized access to the documents as one could simply slip out the parchment and replace the bullae "ring" with one of their choosing.

378:

239:

270:. It gave the names of administrative provinces and the titles of offices such as those of finance and justice. On the other hand, those bullae used for royals and important functionaries generally bear the owner’s bust accompanied by an inscription giving the name and title. Private seals and impressions, distinguished by a single motif sometimes accompanied by an inscription, provide a rich variety of iconographic patterns, largely reflecting the contemporary cultural and religious traditions of Iran, though only indirectly explained by the inscriptions accompany them.

251:

20:

426:

104:

398:

410:

449:

193:

296:

75:

62:

From about the 4th millennium BC onwards, as communications on papyrus and parchment became widespread, bullae evolved into simpler tokens that were attached to the documents with cord, and impressed with a unique sign (i.e., a seal) to provide the same kind of authoritative identification and for tamper-proofing. Bullae are still occasionally attached to documents for these purposes (e.g., the seal on a

95:

impressed into the opening of the bullae to prevent tampering. Each party had its own unique seal to identify them. Seals would not only identify individuals, but it would also identify their office. Sometimes, the token was impressed onto the wet bulla before it dried so that the owner could remember what exactly was in the bulla without having to break it.

176:

have to be broken open to determine the contents. However, by impressing the tokens on the outside of the envelope before sealing them inside, this necessity could be avoided. The outside marks could then serve as a reference and the envelope would only need to be broken open to check the actual contents if there was a dispute about the marks.

91:

for about 4,000 years until the tokens started to become more elaborate in appearance. The tokens were similar in size, material, and color but the markings had more of a variety of shapes. As the amount of goods being produced increased and the exchanging of goods became more common, changes to tokens were made to keep up with the growth.

204:

Designs were inscribed on the clay seals to mark ownership, identify witnesses or partners in commerce, or control of government officials. The later “official” seals were usually larger than private seals and could be designated seals of office, with inscriptions only identifying the office. In many

286:

Within a year of studying these unknown clay marbles, Schmandt-Besserat determined that they were tokens that were supposed to be grouped together and that they thus formed some sort of counting system. The transition between hunting and gathering to settling and agriculture took place in the period

282:

focused much of her career on the discovery of over 8,000 ancient tokens found in the Middle East. She initially visited museums all around the world studying tablets, bricks, and pots and was surprised to find small clay spheres dating from 10,000 to 6,000 BC in every museum. There wasn’t much

179:

A further development involved impressing tokens to make marks on a solid lump of clay or a tablet. Only the tablet was then kept. Because of the complicated shapes and designs of the complex tokens, which did not transfer well by impression, an image of the token would be drawn on the clay instead.

175:

Tokens were collected and stored in bullae, either for future promised transactions or as a record of past transactions. The practice of storing tokens in clay envelopes was more significant for the development of mathematics; initially, because these clay envelopes were not transparent; they would

94:

Transactions for trading needed to be accounted for efficiently, so the clay tokens were placed in a clay ball (bulla), which helped to prevent deception and kept all the tokens together. In order to account for the tokens, the bullae would have to be broken open to reveal their contents. Seals were

460:

119:

During the early Bronze Age, urban economies developed due to urban settlements and the development of trade. The recording of trade became necessary because production, shipments, inventories, and wage payments had to be noted, and merchants needed to preserve records of their transactions. Tokens

265:

era have been discovered at various

Sasanian sites assisting in identifying personal names, government offices, and religious positions. Scholars seem to agree on the typology and purpose of bullae in both civil and domestic environments. The bullae for the administration were generally un-iconic

90:

Clay tokens allowed agriculturalists to keep track of animals and food that had been traded, stored, and/or sold. Because grain production became such a major part of life, they needed to store their extra grain in shared facilities and account for their food. This clay token system went unchanged

188:

As papyrus and parchment gradually replaced clay tablets, bullae became the new encasement for scrolls of this new writing style. Documents were split into two halves, separated in the middle by multiple perforations. The top half was rolled into a scroll and a cord would wrap this section tight,

61:

of the 8th millennium BC onwards, bullae were hollow clay balls that contained other smaller tokens that identified the quantity and types of goods being recorded. In this form, bullae represent one of the earliest forms of specialization in the ancient world, and likely required skill to create.

158:

as early as 3000 BC. From 2600 BC onwards, the

Sumerians wrote multiplication tables, division problems, and geometry on clay tablets. The earliest evidence of the Babylonian numerals also date back to this period. This evidence may suggest that the use of bullae led to early forms of

167:

of the

University of Texas at Austin in the early 1970s is noted for her research and theory of the evolution of bullae into mathematics. She suggested that the earliest tokens were simple shapes and were comparatively unadorned; they represented basic agricultural commodities such as grain and

115:

As the clay tokens and bulla became difficult to store and handle, impressing the tokens on clay tablets became increasingly popular. Clay tablets were easier to store, neater to write on, and less likely to be lost. Impressing the tokens on clay tablets was more efficient but using a stylus to

472:

129:

171:

With the development of cities came a more complex economy and more complex social structures. This complexity was reflected in the tokens, which begin to appear in a much greater diversity of shapes with more complicated designs of incisions and holes.

484:

232:. The Cyrus Cylinder is famous for its suggested evidence of Cyrus' policy of repatriation of the Hebrew people after their captivity in Babylon, as the text refers to the restoration of cult sanctuaries and repatriation of deported peoples.

50:) is an inscribed clay, soft metal (lead or tin), bitumen, or wax token used in commercial and legal documentation as a form of authentication and for tamper-proofing whatever is attached to it (or, in the historical form, contained in it).

180:

This practice, in place by about 3000 BC, afforded greater ease of use and storage, at a price of a certain loss of security. These impressed or drawn marks on the clay tablets were thus the beginnings of a numeration system.

377:

116:

inscribe the impression on the clay tablet was shown to be even more efficient and much faster for the scribes. Around 3100 BC signs expressing numerical value began to appear. At this point, clay tokens became obsolete.

86:

During the period 8,000–7,500 BC, the

Sumerian agriculturalists needed a way to keep records of their animals and goods. Small clay tokens were formed and shaped by the palms to represent certain animals and goods.

120:

were replaced by pictographic tablets that could express not only "how many" but also "where, when, and how." This was the beginning of

Sumerian cuneiform, the first known writing system, in 3100 BC.

283:

information on these clay marbles and archaeologists didn’t know too much about them. Schmandt-Besserat put aside her research on clay and devoted herself to figuring out the use of these clay marbles.

168:

sheep. They could also have a specific shape to represent the quantity of a particular item. For example, two jars of oil would be represented by two ovoids, three jars by three ovoids, and so on.

238:

250:

287:

8,000 to 7,500 BC in the

Ancient Near East and involved a need to store grains and other goods. Schmandt-Besserat discovered that these tokens were used to count food products.

397:

225:. Schemandt-Besserat was able to work back in time and saw the same shapes from cuneiform to pictographs to these tokens. Most of these tokens have no translation though.

228:

Later, tokens transitioned into cylinders. Around the sixth century BC, cylinders were used in international exchanges between empires. A famous one discovered is the

150:

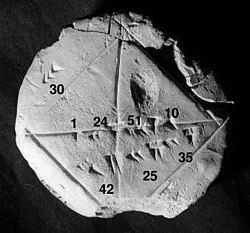

1 + 24/60 + 51/60 + 10/60 = 1.41421296... The tablet also gives an example where one side of the square is 30, and the resulting diagonal is 42 25 35 or 42.4263888...

425:

768:

827:

209:

of the person who made the impression remain visible near the border of the seal in the clay. Various forms of bullae have been found in archeological digs.

832:

366:

Bullae continued through the

Seleucid period of Mesopotamia into Islamic times until paper and wax seals gradually replaced the clay and metal bullae.

218:

409:

511:

817:

752:

563:

466:

Bulla, Spahbed of Nemroz, General of the

Southern Quarter, Sassanian, 6th century AD, from Iraq. The Sulaymaniyah Museum

448:

478:

Bulla, Spahbed of Nemroz, General of the

Southern Quarter, Sassanian, 6th century AD, from Iraq. Sulaymaniyah Museum

244:

Front view of a barrel-shaped clay cylinder resting on a stand. The cylinder is covered with lines of cuneiform text

256:

Rear view of a barrel-shaped clay cylinder resting on a stand. The cylinder is covered with lines of cuneiform text

440:

599:

Postgate, J. N. Early

Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. London: Routledge, 1992. Print.

332:

822:

388:

197:

651:

490:

Bulla, Ostandar of Sin, Governor of Sind/Hind, 6th to 7th century AD, from Iraq. Sulaymaniyah Museum

279:

164:

625:

531:

692:

526:

403:

Same stamped bulla (~12 mm long) showing ridges on cord side indicating papyrus document

160:

19:

8:

436:

709:

578:"Ancient Scripts: Sumerian." Ancient Scripts: Sumerian. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 October 2014.

103:

685:

639:

521:

336:

665:

619:

748:

559:

315:

was eventually applied to seals made out of metal. Although the most typical form of

304:

54:

339:, and various other monarchs in the Middle Ages. A particularly famous type of lead

196:

Multi-stamped bulla (~1" diam.) formerly surrounding a dangling cord; unprovenanced

137:

108:

733:

Denise Schmandt-Besserat. How Writing Came about. Austin: U of Texas, 1996. Print.

416:

217:

The earliest known tokens are those from two sites in the Zagros region of Iran:

40:

78:

Two clay bullae, one complete and sealed, the other broken with tokens visible,

501:

360:

229:

36:

811:

802:

516:

587:

Schmandt-Besserat, Denise. Before Writing. Austin: U of Texas, 1992. Print.

745:"We All Returned as One!": Critical Notes on the Myth of the Mass Return"

356:

328:

206:

141:

79:

58:

24:

506:

348:

267:

222:

63:

192:

23:

A bulla (or clay envelope) and its contents on display at the Louvre.

299:

A modern bulla attached by yellow cord to the Apostolic constitution

155:

384:

295:

262:

133:

74:

145:

136:

with annotations. The diagonal displays an approximation of the

613:

611:

609:

607:

605:

128:

602:

363:

on one side and the name of the issuing Pope on the other.

344:

324:

320:

123:

687:

Stamped and Inscribed Objects from Seleucia on the Tigris

617:

343:

is the one affixed to important documents issued by the

556:

A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC

769:"Sassanian Bulla With Beribboned Ram: Description"

684:

387:, formerly pressed against a cord; unprovenanced

809:

144:figures, 1 24 51 10, which is good to about six

290:

212:

553:

454:Various papal bullae from the twelfth century.

53:In their oldest attested form, as used in the

691:. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. p.

828:Cylinder and impression seals in archaeology

154:The Sumerians developed a complex system of

747:. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. p. 6.

549:

547:

512:List of artifacts significant to the Bible

419:. Note the lead seal attached to the cord.

383:Stamped clay bulla sealed by a servant of

833:Ancient Near and Middle East clay objects

682:

544:

294:

191:

127:

102:

73:

18:

16:Device to seal or authenticate documents

742:

704:

702:

183:

124:Precursor to mathematics and accounting

98:

810:

595:

593:

327:, as the ones affixed to the several

82:. Oriental Institute Museum, Chicago.

699:

666:"Tokens: the origin of mathematics"

590:

558:(2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell.

13:

14:

844:

796:

683:McDowell, Robert (January 1935).

621:Tokens: the origin of mathematics

261:A number of clay bullae from the

789:Austin: U of Texas, 1996. Print.

483:

471:

459:

447:

424:

408:

396:

376:

351:for the type of seal, where the

249:

237:

779:

761:

736:

618:Eleanor Robson, D.J. Melville.

439:, issued by Holy Roman Emperor

727:

676:

658:

581:

572:

278:French-American archaeologist

1:

818:8th-century BC establishments

803:details on the Hezekian bulla

554:Van De Mieroop, Marc (2007).

537:

291:Metal bullae and later usage

213:Archeological finds and digs

7:

495:

323:, it was sometimes made of

273:

10:

849:

785:Denise Schmandt-Besserat.

369:

69:

773:The Barakat Gallery Store

391:collection of antiquities

200:collection of antiquities

198:Redondo Beach, California

46:, "bubble, blob"; plural

39:for "a round seal", from

670:Mesopotamian Mathematics

280:Denise Schmandt-Besserat

165:Denise Schmandt-Besserat

787:How Writing Came About.

626:St. Lawrence University

355:has an image of Saints

132:Babylonian clay tablet

532:History of mathematics

308:

201:

151:

112:

111:used inside of a bulla

83:

28:

743:Becking, Bob (2006).

714:Encyclopaedia Iranica

527:History of accounting

298:

195:

131:

106:

77:

22:

184:Clay bullae as seals

99:Precursor to writing

437:Golden Bull of 1356

337:Holy Roman Emperors

522:History of writing

333:Byzantine Emperors

309:

202:

152:

113:

84:

29:

754:978-1-57506-104-7

565:978-1-4051-4911-2

305:Pope Benedict XVI

223:Ganj-i-Dareh Tepe

109:accounting tokens

55:ancient Near East

840:

823:Seals (insignia)

790:

783:

777:

776:

765:

759:

758:

740:

734:

731:

725:

724:

722:

720:

706:

697:

696:

690:

680:

674:

673:

662:

656:

655:

649:

645:

643:

635:

633:

632:

615:

600:

597:

588:

585:

579:

576:

570:

569:

551:

487:

475:

463:

451:

428:

412:

400:

380:

301:Magni aestimamus

266:and exclusively

253:

241:

159:mathematics and

138:square root of 2

848:

847:

843:

842:

841:

839:

838:

837:

808:

807:

799:

794:

793:

784:

780:

767:

766:

762:

755:

741:

737:

732:

728:

718:

716:

708:

707:

700:

681:

677:

664:

663:

659:

647:

646:

637:

636:

630:

628:

624:. published by

616:

603:

598:

591:

586:

582:

577:

573:

566:

552:

545:

540:

498:

491:

488:

479:

476:

467:

464:

455:

452:

443:

429:

420:

417:Pope Urban VIII

413:

404:

401:

392:

381:

372:

293:

276:

257:

254:

245:

242:

215:

186:

149:

126:

101:

72:

41:Classical Latin

27:(4000–3100 BC).

17:

12:

11:

5:

846:

836:

835:

830:

825:

820:

806:

805:

798:

797:External links

795:

792:

791:

778:

760:

753:

735:

726:

698:

675:

657:

648:|website=

601:

589:

580:

571:

564:

542:

541:

539:

536:

535:

534:

529:

524:

519:

514:

509:

504:

502:Bulla (amulet)

497:

494:

493:

492:

489:

482:

480:

477:

470:

468:

465:

458:

456:

453:

446:

444:

430:

423:

421:

414:

407:

405:

402:

395:

393:

382:

375:

371:

368:

331:issued by the

292:

289:

275:

272:

259:

258:

255:

248:

246:

243:

236:

230:Cyrus Cylinder

214:

211:

185:

182:

125:

122:

100:

97:

71:

68:

37:Medieval Latin

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

845:

834:

831:

829:

826:

824:

821:

819:

816:

815:

813:

804:

801:

800:

788:

782:

774:

770:

764:

756:

750:

746:

739:

730:

715:

711:

705:

703:

694:

689:

688:

679:

671:

667:

661:

653:

641:

627:

623:

622:

614:

612:

610:

608:

606:

596:

594:

584:

575:

567:

561:

557:

550:

548:

543:

533:

530:

528:

525:

523:

520:

518:

517:Seal (emblem)

515:

513:

510:

508:

505:

503:

500:

499:

486:

481:

474:

469:

462:

457:

450:

445:

442:

438:

434:

427:

422:

418:

411:

406:

399:

394:

390:

389:Redondo Beach

386:

385:King Hezekiah

379:

374:

373:

367:

364:

362:

358:

354:

350:

346:

342:

338:

334:

330:

326:

322:

318:

314:

306:

302:

297:

288:

284:

281:

271:

269:

264:

252:

247:

240:

235:

234:

233:

231:

226:

224:

220:

210:

208:

199:

194:

190:

181:

177:

173:

169:

166:

162:

157:

147:

143:

139:

135:

130:

121:

117:

110:

105:

96:

92:

88:

81:

76:

67:

65:

60:

56:

51:

49:

45:

42:

38:

34:

26:

21:

786:

781:

772:

763:

744:

738:

729:

717:. Retrieved

713:

686:

678:

669:

660:

629:. Retrieved

620:

583:

574:

555:

432:

365:

352:

340:

329:Golden Bulls

319:was made of

316:

312:

310:

300:

285:

277:

260:

227:

216:

207:fingerprints

203:

187:

178:

174:

170:

153:

118:

114:

93:

89:

85:

52:

47:

43:

32:

30:

349:Papal bulls

142:sexagesimal

80:Uruk period

59:Middle East

25:Uruk period

812:Categories

719:29 October

631:2015-10-30

538:References

507:Papal bull

441:Charles IV

415:A bull of

303:issued by

268:epigraphic

219:Tepe Asiab

161:accounting

64:papal bull

650:ignored (

640:cite book

347:, called

311:The term

156:metrology

710:"Bullae"

496:See also

307:in 2011.

274:Research

263:Sasanian

140:in four

134:YBC 7289

57:and the

435:of the

370:Gallery

205:cases,

148:digits.

146:decimal

70:Origins

751:

562:

48:bullae

433:bulla

357:Peter

353:bulla

341:bulla

317:bulla

313:bulla

107:Clay

44:bulla

33:bulla

749:ISBN

721:2014

652:help

560:ISBN

431:The

361:Paul

359:and

345:Pope

325:gold

321:lead

221:and

66:).

814::

771:.

712:.

701:^

668:.

644::

642:}}

638:{{

604:^

592:^

546:^

335:,

163:.

31:A

775:.

757:.

723:.

695:.

693:2

672:.

654:)

634:.

568:.

35:(

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.