285:

404:

304:

Lucian, an ancient Greek philosopher, postulated another principle. He believed athletes should always train in "exuberated conditions." His idea was that training should take place outdoors in the sun every day of the year. He thought that the body should be beautiful, tanned, and lean to perform its best. During workouts, he believed athletes should work as hard as possible. When training in the gymnasium, his idea was that one should not run or exercise on the stone floor but on sand instead to add difficulty. An exercise he invented involved a long jump where athletes would run and jump high into the air wearing weighted suspenders. Another exercise he developed was for athletes to jump over

19:

372:

158:

281:, an ancient Greek physician, believed that athletes who walked after exercising would have a stronger and more rested body. Because of his beliefs, ancient Greek athletes ended each workout with a low-intensity cool down. Aristotle observed that athletes who have a rest day should not rest completely but do a mild, low-intensity workout instead. These practices are still in use today because of how well-founded the early principles had been (Stefanović et al. 112).

392:

93:

300:, which is a curved stick. They would rub the oil on their skin and then scrape it off using the strigil. In this way, they would clean themselves (The Olympic Games 5). After exercising, they also often had a bath and a massage. Massages would consist of gentle movements and stretching of their arms and legs (Stefanović et al. 112).

342:

Because of these gifts, athletes were able to afford much meat. Today, scientific advancements allow trainers to prescribe specific diets to athletes, but, even in ancient times without modern scientific knowledge, the Greeks were able to recognize food's beneficial effects on an athlete's diet (Briers 12-13).

269:

This was the basic training structure practiced throughout ancient Greece. In order to create the optimal training structure for any given day, however, the trainers would consider many factors such as the place, the time, upcoming events, and the athlete's physical and mental condition. The training

316:

The ancient Greeks divided athletes into three age categories, similar to what is done today. Each age category would have its separate set of coaches. The training programs for each age level varied, growing increasingly strenuous the older the athletes were. Certain coaches were selected to scout

73:

In the ancient sources, training is often discussed. However, details about how the training of runners compared to the training of other types of athletes are not clearly addressed. In ancient Greece, athletes might not have been as specialized as they are today. It is likely that a single athlete

303:

Trainers and philosophers had many ideas about specific ways of training. One practice that developed had athletes exercise with 3-pound (1.4 kg) weights in each hand. This practice helped improve arm strength, which is beneficial for running, throwing the javelin, swimming, and martial arts.

379:

Although many people in ancient Greece liked sports, not all philosophers thought that intense training was good. Aristotle believed that fitness should be a part of children's education, but that over-training was bad. In ancient Greece there were four main parts to education: reading, writing,

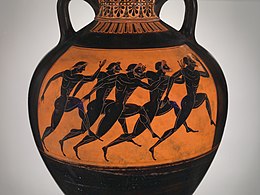

341:

grew very well in Greece and were the primary part of everyone's diet up until fifth century BCE. At that time, trainers recognized that meat was key in building muscle. At this same point in history, sports were becoming increasingly popular and athletes were given large gifts by rich admirers.

454:

Perrottet, n.1 above at 18-20. "As if it weren't enough for the ancient Greeks to have established the foundations of

Western philosophy, geometry, drama, art, and science, we can also thank them for creating our modern passion for sport." Id. at 18. "The Greeks held races . . . at weddings and

54:, for example, was so important that "he Olympiad would be named after the victor, and since history itself was dated by the Games, it was he who thus gained the purest dose of immortality." The Olympic Games hosted a large variety of running events, each with its own set of rules. The ancient

195:

in 490 BC. In 1896, at the first modern

Olympics, the very first modern-day marathon was run. To honor the history of Greek running, Greece chose a course that would mimic the route run by Athenian army. The route started at a bridge in the town of Marathon and ended in the Olympic stadium.

380:

gymnastic exercises, and music. Aristotle thought that an appropriate amount of exercise was a key part of education; however, he recognized how much some athletes over-trained. Aristotle referred to the excessive training that many competitive athletes did as “evil” (Stefanović et al. 113).

362:

player. The aulos player's job was to produce rhythmical music in order to help the athletes, particularly when warming up. The athletes were supposed to focus primarily on accurately performing the exercises according to their trainer's advice; however, music was a key part of their warm up

251:

in ancient Greece became a very scientific and philosophical field of study and practice. Many philosophers had their own ideas about how athletes should train. By the fourth century BCE, sports in ancient Greece became so competitive and advanced that specialized coaches developed for each

74:

would have trained for, and competed in, many different events resulting in less distinction being drawn between training for different events. Many philosophers had ideas about how athletes should train, which provides historians with numerous insights. For example,

65:

The people of Greece generally enjoyed sporting events, particularly foot racing, and wealthy admirers would often give large gifts to successful athletes. Though foot races were physically challenging, if successful, athletes could become very wealthy. The ancient

600:

July 21, 2021. "The

Ancient Olympics never had a ceremony (or even an athletic event) involving a torch as a central element . . . The Olympic torch relay as we know it today has a much shadier and more recent origin. It was invented for the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

596:("Though the ancient Olympics were also a religious festival, they did not feature a torch-race. In spite of that, the Greek torch-race was a source of inspiration for the introduction of the Olympic flame at the Berlin games of 1936." See also Open University,

117:

would exercise the whole body, which is a principle that many later ancient Greek athletes lived by. The first

Olympians believed that to have a harmonious body, the entire body must be trained, which would result in fierce warriors and strong athletes.

154:, which was a long-distance race that was 20 or 24 stades long, or about two and a half miles to three miles. For races longer than one stade, runners would have to turn 180 degrees around a post at each of the two ends of the stadium (Flaceliere 106).

83:

in athletic training and the diet of athletes. Professional runners known as "hēmerodromoi", the messengers who were informational lifeline of an empire. They were running across rugged terrains and paths to convey vital information in battles.

78:

argued that the whole body should be trained to increase strength and speed for running and wrestling (Stefanović et al. 113). The lengths and types of foot races are widely written. Also discussed in a variety of sources is the use of

252:

particular sport. These coaches were known as gymnasts. Along with specialized coaches, a new system of training was developed—the tetras. This was a four-day cycle of varying training. The tetras had the following structure:

674:

58:

developed difficult training programs with specialized trainers in preparation for the Games. The training and competitive attitude of Greek athletes gives insight into how scientifically advanced

329:

to athletes. Most people in ancient Greece only ate meat during religious festivals. Only the rich could have afforded it on a regular basis, but meat was still just a minor part of their diet.

432:(2009) p.145. Perrottet notes that Greek historians referred to a date that we would call 457 B.C. as "the third year of the Eighteenth Olympiad, when Ladas of Argos won the stadion." Id.

191:. What is called a marathon today gets its name from the 40-kilometre (24.85 mi) distance covered by the Athenian army runnig back to the city after battle with Persians at

317:

for young boys who looked particularly strong and fit. These boys would be selected to start training with the young men as soon as they were old enough (Stefanović et al.113).

146:

race was the most prestigious; the mythical founder of the

Olympic Games could allegedly run it in one breath. Other running events included a two-stade race, the

179:, which reflected the games' origins as a means of training for warfare. Contrary to popular belief there was no ceremonial torch-race or torch lighting at the

769:

270:

also differed depending on whether it was done indoors or outdoors. Based on these factors, the trainer would adjust the workout (Stefanović et al. 113).

284:

107:

involved well-trained warriors competing in a variety of events. The warriors did not have any specialized training for the

Olympics. Each

22:

231:

describes a man's ultimate physical beauty as a body capable of enduring all challenges. This is why he viewed the athletes in the

130:

There were many lengths and types of foot races in ancient Greece. The standard distance that these races were measured in was the

113:

in ancient Greece had its training program for soldiers, which was the only preparation they had. However, to train for war, the

265:

Day Four – the day of medium intensity. Athletes mainly practiced wrestling on this day, focusing more on tactics than strength.

738:

712:

350:

Ancient Greeks believed that training and music should be experienced together because they both pleased man's spirit.

602:

227:. This race reflected the ancient Greek belief that one's body should be strong as a whole and not just in one area.

809:

613:

325:

Along with developing training programs and stretching exercises, the ancient Greeks also introduced special

97:

The Death of Ladas, The Greek Runner, Who Died When

Receiving the Crown of Victory in the Temple of Olympia

830:

441:

Regarding training in general, see

Perrottet, n.1 above at 31-34, & M.I. Finley & H.W. Pleket,

355:

26:

408:

262:

Day Three – the day of resting. On this day athletes would do short mild workouts and primarily rest.

248:

187:

there was none at the

Olympic games. One event that was not ever in the ancient Olympic Games is the

18:

50:

788:

825:

351:

259:

Day Two – the day of intensity. It involved the athlete going through long, strenuous exercises.

122:

later said that the training of the whole body infuses it with courage (Stefanović et al. 113).

795:

147:

142:

396:

256:

Day One – the day of preparations. It consisted of toning and short, high-intensity workouts.

200:

180:

104:

45:

593:

371:

292:

The ancient Greeks also valued rest after exercising. After a workout, athletes used their

750:

8:

168:

651:

626:

802:

734:

708:

656:

184:

704:

646:

638:

603:

https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/history/the-olympic-torch-the-truth

554:

See

Perrottet, n.1 above at 138-146, & Finley & Pleket, n.2 above at 35-37.

375:

Runners featured on an Attic black-figure Panathenaic prize amphora (c. 530–520 BC)

326:

192:

70:

developed running as a sport into a sophisticated field of science and philosophy.

507:

483:

183:. Although a torch-race was conducted at several religious festivals, such as the

755:

729:

699:

151:

137:

132:

244:

114:

33:

614:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/liveonline/02/sports/swaddling021902.htm

819:

176:

161:

157:

531:

165:

660:

642:

40:

can be traced back to 776 BC. Running was important to members of ancient

724:

278:

338:

334:

232:

204:

44:

society, and is consistently highlighted in documents referencing the

293:

228:

224:

119:

92:

288:

Attic kylix with athlete cleansing himself with a strigil, 430-20 BC

188:

770:"Syncretism of coaching science in ancient Greece and modern times

305:

297:

220:

216:

212:

37:

330:

208:

67:

59:

55:

41:

359:

109:

80:

75:

627:"Run, Philippides, Run! The Story of the Battle of Marathon"

308:

with lead weights in their hands (Stefanović et al. 114).

791:. 2nd ed. N.p.: n.p., 2007. Olympic.org. 5 December 2009.

594:

http://ancientolympics.arts.kuleuven.be/eng/TC002eEN.html

805:" The Ancient Olympics. N.p., n.d. Web. 5 December 2009.

532:"Day Runners of Ancient Greece, Heroes of Communication"

798:" The Olympic Games. N.p., n.d. Web. 5 December 2009.

354:was used both in training and in competition. Each

207:. The pentathlon was a combination of five events:

817:

691:

175:In the Olympics, there was a race in armor, the

508:"The ancient athlete: amateur or professional?"

484:"The ancient athlete: amateur or professional?"

812:" BBC History. BBC, n.d. Web. 5 December 2009.

768:Stefanović, Đ., T. Ioannidis, and M. Kariofu.

744:

756:Daily life in Greece at the time of Pericles

273:

23:Euphiletos Painter Panathenaic prize amphora

700:Sporting success in ancient Greece and Rome

443:The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years

718:

650:

776:2.1–4 (2008): 111–121 . ISSN 1820-6301."

733:. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 2002 .

675:"Aristotle, Rhetoric, Bekker page 1361b"

370:

283:

156:

91:

17:

762:

818:

624:

125:

87:

235:as the most beautiful of them all.

13:

774:Serbian journal of sports sciences

247:developed, sports also developed.

140:is approximately 185 meters). The

14:

842:

697:Audrey Briers; Ashmolean Museum.

311:

296:, a special bottle of oil, and a

730:Sports and games of the ancients

402:

390:

366:

667:

618:

584:

575:

566:

557:

789:The Olympic Games in Antiquity

548:

524:

500:

476:

467:

458:

448:

435:

422:

1:

759:. New York: Macmillan; 1965 .

605:. See also Judith Swaddling,

598:The Olympic Torch: The Truth,

414:

409:Sport of athletics portal

581:Perrottet, n.1 above at 179.

572:Perrottet, n.1 above at 138.

7:

796:Olympic Sports- Foot Races.

563:Perrottet, n.1 above at 138

464:Perrottet, n.1 above at 52.

383:

238:

10:

847:

782:

607:The Ancient Olympic Games,

27:Metropolitan Museum of Art

25:depicting a running race,

397:Ancient Greece portal

274:Trainers and philosophers

62:was for the time period.

363:(Stefanović et al.112).

345:

320:

99:by George Murray, 1899.

376:

289:

172:

148:Diaulos (running race)

100:

29:

679:www.perseus.tufts.edu

643:10.1136/bjsm.15.3.186

536:www.sportsgearmag.com

512:www.perseus.tufts.edu

488:www.perseus.tufts.edu

374:

287:

201:ancient Olympic Games

199:Another event in the

181:Ancient Olympic Games

160:

105:Ancient Olympic Games

95:

46:Ancient Olympic Games

21:

610:The Washington Post,

455:funerals. Id. at 20.

625:Grogan, R. (1981).

430:The Naked Olympics,

169:Panathenaic amphora

126:Types of foot races

88:Early Olympic Games

377:

290:

173:

101:

30:

831:Running in Greece

751:Robert Flacelière

739:978-0-313-31600-5

713:978-1-85444-055-6

631:Br. J. Sports Med

591:Ancient Olympics,

358:had at least one

185:Panathenaic Games

36:, the history of

838:

777:

766:

760:

748:

742:

722:

716:

705:Ashmolean Museum

695:

689:

688:

686:

685:

671:

665:

664:

654:

622:

616:

588:

582:

579:

573:

570:

564:

561:

555:

552:

546:

545:

543:

542:

528:

522:

521:

519:

518:

504:

498:

497:

495:

494:

480:

474:

471:

465:

462:

456:

452:

446:

445:(1976) pp.88-97.

439:

433:

428:Tony Perrottet,

426:

407:

406:

405:

395:

394:

393:

846:

845:

841:

840:

839:

837:

836:

835:

816:

815:

810:Running events.

785:

780:

767:

763:

749:

745:

723:

719:

696:

692:

683:

681:

673:

672:

668:

623:

619:

589:

585:

580:

576:

571:

567:

562:

558:

553:

549:

540:

538:

530:

529:

525:

516:

514:

506:

505:

501:

492:

490:

482:

481:

477:

472:

468:

463:

459:

453:

449:

440:

436:

427:

423:

417:

403:

401:

391:

389:

386:

369:

348:

323:

314:

276:

241:

128:

90:

12:

11:

5:

844:

834:

833:

828:

826:Ancient Greece

814:

813:

806:

799:

792:

784:

781:

779:

778:

761:

743:

717:

690:

666:

637:(3): 186–189.

617:

612:Feb. 19, 2002

583:

574:

565:

556:

547:

523:

499:

475:

466:

457:

447:

434:

420:

416:

413:

412:

411:

399:

385:

382:

368:

365:

347:

344:

322:

319:

313:

312:Age categories

310:

275:

272:

267:

266:

263:

260:

257:

245:ancient Greece

240:

237:

164:from an Attic

127:

124:

115:ancient Greeks

89:

86:

34:Ancient Greece

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

843:

832:

829:

827:

824:

823:

821:

811:

807:

804:

800:

797:

793:

790:

787:

786:

775:

771:

765:

758:

757:

752:

747:

740:

736:

732:

731:

726:

721:

714:

710:

706:

702:

701:

694:

680:

676:

670:

662:

658:

653:

648:

644:

640:

636:

632:

628:

621:

615:

611:

608:

604:

599:

595:

592:

587:

578:

569:

560:

551:

537:

533:

527:

513:

509:

503:

489:

485:

479:

473:Id. at 53-54.

470:

461:

451:

444:

438:

431:

425:

421:

419:

410:

400:

398:

388:

387:

381:

373:

367:Over-training

364:

361:

357:

353:

343:

340:

336:

332:

328:

318:

309:

307:

301:

299:

295:

286:

282:

280:

271:

264:

261:

258:

255:

254:

253:

250:

246:

236:

234:

230:

226:

222:

218:

214:

210:

206:

202:

197:

194:

190:

186:

182:

178:

177:hoplitodromos

170:

167:

163:

162:Hoplitodromos

159:

155:

153:

149:

145:

144:

139:

135:

134:

123:

121:

116:

112:

111:

106:

98:

94:

85:

82:

77:

71:

69:

63:

61:

57:

53:

52:

47:

43:

39:

35:

28:

24:

20:

16:

773:

764:

754:

746:

728:

720:

698:

693:

682:. Retrieved

678:

669:

634:

630:

620:

609:

606:

597:

590:

586:

577:

568:

559:

550:

539:. Retrieved

535:

526:

515:. Retrieved

511:

502:

491:. Retrieved

487:

478:

469:

460:

450:

442:

437:

429:

424:

418:

378:

349:

324:

315:

302:

291:

277:

268:

242:

198:

174:

171:, 323–322 BC

166:black-figure

141:

131:

129:

108:

102:

96:

72:

64:

49:

31:

15:

725:Steve Craig

279:Hippocrates

136:(where one

820:Categories

703:. Oxford:

684:2023-06-05

541:2023-09-11

517:2022-02-22

493:2022-02-22

415:References

335:vegetables

233:pentathlon

205:pentathlon

707:; 1994 .

356:gymnasium

294:aryballos

249:Athletics

229:Aristotle

225:wrestling

120:Aristotle

803:Running.

384:See also

239:Training

203:was the

193:Marathon

189:marathon

152:dolichos

150:and the

783:Sources

661:7023595

652:1858762

306:hurdles

298:strigil

221:running

217:jumping

213:javelin

143:stadion

51:stadion

38:running

737:

711:

659:

649:

339:grains

337:, and

331:Fruits

209:discus

138:stadia

68:Greeks

60:Greece

56:Greeks

48:. The

360:aulos

352:Music

346:Music

327:diets

133:stade

110:polis

81:music

76:Plato

42:Greek

735:ISBN

709:ISBN

657:PMID

321:Diet

223:and

103:The

772:."

647:PMC

639:doi

243:As

32:In

822::

753:.

727:.

677:.

655:.

645:.

635:15

633:.

629:.

534:.

510:.

486:.

333:,

219:,

215:,

211:,

808:"

801:"

794:"

741:.

715:.

687:.

663:.

641::

544:.

520:.

496:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.