337:). Protoperithecia are formed most readily in the laboratory when growth occurs on solid (agar) synthetic medium with a relatively low source of nitrogen. Nitrogen starvation appears to be necessary for expression of genes involved in sexual development. The protoperithecium consists of an ascogonium, a coiled multicellular hypha that is enclosed in a knot-like aggregation of hyphae. A branched system of slender hyphae, called the trichogyne, extends from the tip of the ascogonium projecting beyond the sheathing hyphae into the air. The sexual cycle is initiated (i.e. fertilization occurs) when a cell (usually a conidium) of opposite mating type contacts a part of the trichogyne (see

397:

for 30 minutes to induce germination. For normal strains, the entire sexual cycle takes 10 to 15 days. In a mature ascus containing 8 ascospores, pairs of adjacent spores are identical in genetic constitution, since the last division is mitotic, and since the ascospores are contained in the ascus sac that holds them in a definite order determined by the direction of nuclear segregations during meiosis. Since the four primary products are also arranged in sequence, the pattern of genetic markers from a first-division segregation can be distinguished from the markers from a second-division segregation pattern.

310:

341:). Such contact can be followed by cell fusion leading to one or more nuclei from the fertilizing cell migrating down the trichogyne into the ascogonium. Since both ‘A’ and ‘a’ strains have the same sexual structures, neither strain can be regarded as exclusively male or female. However, as a recipient, the protoperithecium of both the ‘A’ and ‘a’ strains can be thought of as the female structure, and the fertilizing conidium can be thought of as the male participant.

314:

occur between individual strains of different mating type, ‘A’ and ‘a’. Fertilization occurs by the passage of nuclei of conidia or mycelium of one mating type into the protoperithecia of the opposite mating type through the trichogyne. Fusion of the nuclei of opposite mating types occurs within the protoperithecium to form a zygote (2N) nucleus.

349:

become associated and begin to divide synchronously. The products of these nuclear divisions (still in pairs of unlike mating type, i.e. ‘A’ / ‘a’) migrate into numerous ascogenous hyphae, which then begin to grow out of the ascogonium. Each of these ascogenous hypha bends to form a hook (or crozier)

396:

A mature perithecium may contain as many as 300 asci, each derived from identical fusion diploid nuclei. Ordinarily, in nature, when the perithecia mature the ascospores are ejected rather violently into the air. These ascospores are heat resistant and, in the lab, require heating at 60 °C

313:

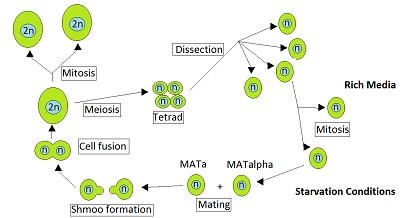

Neurospora crassa life cycle. The haploid mycelium reproduces asexually by two processes: (1) simple proliferation of existing mycelium, and (2) formation of conidia (macro- and micro-) which can be dispersed and then germinate to produce new mycelium. In the sexual cycle, mating can only

124:

reproduces by mitosis as either haploid or diploid cells. However, when starved, diploid cells undergo meiosis to form haploid spores. Mating occurs when haploid cells of opposite mating type, MATa and MATα, come into contact. Ruderfer et al. pointed out that such contacts are frequent between

83:) are called "pseudo-homothallic". Instead of separating into four individual spores by two meiosis events, only a single meiosis occurs, resulting in two spores, each with two haploid nuclei of different mating types (those of its parents). This results in a spore which can mate with itself (

220:

occurs in areas with widely different climates and environments, it displays low genetic variation and lack of population genetic differentiation on a global scale. Thus the capability for heterothallic sex is maintained even though little genetic diversity is produced. As in the case of

344:

The subsequent steps following fusion of ‘A’ and ‘a’ haploid cells, have been outlined by

Fincham and Day, and by Wagner and Mitchell. After fusion of the cells, the further fusion of their nuclei is delayed. Instead, a nucleus from the fertilizing cell and a nucleus from the

157:) are unlikely to be sufficient for generally maintaining sex from one generation to the next. Rather, a short-term benefit, such as meiotic recombinational repair of DNA damages caused by stressful conditions such as starvation may be the key to the maintenance of sex in

608:

Birdsell JA, Wills C (2003). The evolutionary origin and maintenance of sexual recombination: A review of contemporary models. Evolutionary

Biology Series >> Evolutionary Biology, Vol. 33 pp. 27–137. MacIntyre, Ross J.; Clegg, Michael, T (Eds.), Springer.

152:

is heterothallic, it appears that, in nature, mating is most often between closely related yeast cells. The relative rarity in nature of meiotic events that result from outcrossing suggests that the possible long-term benefits of outcrossing (e.g. generation of

275:

is sexually reproducing, but recombination in natural populations is most likely to occur across spatially and genetically limited distances resulting in a highly clonal population structure. Sex is maintained in this species even though very little

332:

has two mating types that, in this case, are symbolized by ‘A’ and ‘a’. There is no evident morphological difference between the ‘A’ and 'a' mating type strains. Both can form abundant protoperithecia, the female reproductive structure (see

350:

at its tip and the ‘A’ and ‘a’ pair of haploid nuclei within the crozier divide synchronously. Next, septa form to divide the crozier into three cells. The central cell in the curve of the hook contains one ‘A’ and one ‘a’ nucleus (see

392:

As the above events are occurring, the mycelial sheath that had enveloped the ascogonium develops as the wall of the perithecium, becomes impregnated with melanin, and blackens. The mature perithecium has a flask-shaped structure.

250:, causing aspergillosis in immunocompromised individuals. In 2009, a sexual state of this heterothallic fungus was found to arise when strains of opposite mating type were cultured together under appropriate conditions.

119:

is heterothallic. This means that each yeast cell is of a certain mating type and can only mate with a cell of the other mating type. During vegetative growth that ordinarily occurs when nutrients are abundant,

893:

Henk DA, Shahar-Golan R, Devi KR, Boyce KJ, Zhan N, Fedorova ND, Nierman WC, Hsueh PR, Yuen KY, Sieu TP, Kinh NV, Wertheim H, Baker SG, Day JN, Vanittanakom N, Bignell EM, Andrianopoulos A, Fisher MC (2012).

377:. The two sequential divisions of meiosis lead to four haploid nuclei, two of the ‘A’ mating type and two of the ‘a’ mating type. One further mitotic division leads to four ‘A’ and four ‘a’ nuclei in each

137:, and these cells can mate with each other. The second reason is that haploid cells of one mating type, upon cell division, often produce cells of the opposite mating type with which they may mate.

373:. The diploid nucleus has 14 chromosomes formed from the two fused haploid nuclei that had 7 chromosomes each. Formation of the diploid nucleus is immediately followed by

103:

144:

populations clonal reproduction and a type of “self-fertilization” (in the form of intratetrad mating) predominate. Ruderfer et al. analyzed the ancestry of natural

268:

Henk et al. showed that the genes required for meiosis are present in T. marneffei, and that mating and genetic recombination occur in this species.

189:, is widespread in nature, and is typically found in soil and decaying organic matter, such as compost heaps, where it plays an essential role in

643:

Sugui JA, Losada L, Wang W, Varga J, Ngamskulrungroj P, Abu-Asab M, Chang YC, O'Gorman CM, Wickes BL, Nierman WC, Dyer PS, Kwon-Chung KJ (2011).

324:

is heterothallic. Sexual fruiting bodies (perithecia) can only be formed when two mycelia of different mating type come together. Like other

205:(2–3 μm) that readily become airborne. A. fumigatus possesses a fully functional sexual reproductive cycle that leads to the production of

692:

O'Gorman CM, Fuller H, Dyer PS (January 2009). "Discovery of a sexual cycle in the opportunistic fungal pathogen

Aspergillus fumigatus".

362:

that can grow to form a further crozier that can then form its own ascus-initial cell. This process can then be repeated multiple times.

517:

Ruderfer DM, Pratt SC, Seidel HS, Kruglyak L (September 2006). "Population genomic analysis of outcrossing and recombination in yeast".

745:"Low genetic variation and no detectable population structure in aspergillus fumigatus compared to closely related Neosartorya species"

46:

In heterothallic fungi, two different individuals contribute nuclei to form a zygote. Examples of heterothallism are included for

839:

Moore GG, Elliott JL, Singh R, Horn BW, Dorner JW, Stone EA, Chulze SN, Barros GG, Naik MK, Wright GC, Hell K, Carbone I (2013).

125:

closely related yeast cells for two reasons. The first is that cells of opposite mating type are present together in the same

896:"Clonality despite sex: the evolution of host-associated sexual neighborhoods in the pathogenic fungus Penicillium marneffei"

630:

614:

365:

After formation of the ascus-initial cell, the ‘A’ and ‘a’ nucleus fuse with each other to form a diploid nucleus (see

257:, suggesting that production of genetic variation may contribute to the maintenance of heterothallism in this species.

385:

is an essential part of the life cycle of all sexually reproducing organisms, and in its main features, meiosis in

562:"Heterothallism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolates from nature: effect of HO locus on the mode of reproduction"

945:

Westergaard M, Mitchell HK (1947). "Neurospora. Part V. A synthetic medium favoring sexual reproduction".

225:, above, a short-term benefit of meiosis may be the key to the adaptive maintenance of sex in this species.

560:

Katz Ezov T, Chang SL, Frenkel Z, Segrè AV, Bahalul M, Murray AW, Leu JY, Korol A, Kashi Y (January 2010).

148:

strains and concluded that outcrossing occurs only about once every 50,000 cell divisions. Thus, although

793:

354:). This binuclear cell initiates ascus formation and is called an “ascus-initial” cell. Next the two

973:

31:

that reside in different individuals. The term is applied particularly to distinguish heterothallic

115:

48:

427:

1073:

173:

76:

is given in some detail, since similar life cycles are present in other heterothallic fungi.

62:

52:

701:

8:

841:"Sexuality generates diversity in the aflatoxin gene cluster: evidence on a global scale"

277:

40:

705:

998:

958:

922:

895:

867:

840:

821:

769:

744:

725:

669:

644:

586:

561:

542:

56:

491:

466:

1078:

1049:

1026:

1003:

927:

872:

813:

774:

717:

674:

626:

610:

591:

577:

534:

496:

447:

443:

359:

320:

154:

130:

68:

825:

358:

cells on either side of the first ascus-forming cell fuse with each other to form a

993:

985:

954:

917:

907:

862:

852:

805:

764:

756:

729:

709:

664:

656:

645:"Identification and characterization of an Aspergillus fumigatus "supermater" pair"

581:

573:

526:

486:

482:

478:

439:

182:

84:

546:

989:

912:

857:

406:

760:

309:

240:

1067:

451:

426:

Billiard, S.; LóPez‐Villavicencio, M.; Hood, M. E.; Giraud, T. (June 2012).

931:

876:

817:

778:

721:

678:

595:

538:

428:"Sex, outcrossing and mating types: unsolved questions in fungi and beyond"

1007:

660:

625:

Elvira Hörandl (2013). Meiosis and the

Paradox of Sex in Nature, Meiosis,

500:

355:

36:

713:

369:). This nucleus is the only diploid nucleus in the entire life cycle of

1053:

1030:

346:

325:

210:

35:, which require two compatible partners to produce sexual spores, from

425:

243:

88:

809:

530:

247:

206:

202:

198:

194:

246:

in crops worldwide. It is also an opportunistic human and animal

382:

374:

134:

24:

253:

Sexuality generates diversity in the aflatoxin gene cluster in

190:

102:

378:

126:

32:

516:

177:, is a heterothallic fungus. It is one of the most common

559:

467:"Life cycle of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae"

892:

281:

94:

28:

691:

260:

164:

838:

742:

642:

140:

Katz Ezov et al. presented evidence that in natural

944:

228:

299:

1025:. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

1065:

971:

791:

974:"Sexual development genes of Neurospora crassa"

197:recycling. Colonies of the fungus produce from

1043:

743:Rydholm C, Szakacs G, Lutzoni F (April 2006).

1020:

832:

785:

464:

972:Nelson MA, Metzenberg RL (September 1992).

965:

794:"Sexual reproduction in Aspergillus flavus"

736:

685:

636:

553:

181:species to cause disease in humans with an

512:

510:

458:

288:by a short-term benefit of meiosis, as in

18:Sexes that reside in different individuals

997:

921:

911:

866:

856:

768:

668:

585:

490:

308:

101:

888:

886:

602:

507:

366:

351:

338:

334:

133:of cells directly produced by a single

79:Certain heterothallic species (such as

1066:

1048:. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

792:Horn BW, Moore GG, Carbone I (2009).

883:

389:seems typical of meiosis generally.

72:. The heterothallic life cycle of

13:

959:10.1002/j.1537-2197.1947.tb13032.x

14:

1090:

578:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04436.x

444:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2012.02495.x

1044:Wagner RP, Mitchell HK (1964).

1037:

1014:

938:

432:Journal of Evolutionary Biology

201:thousands of minute grey-green

619:

483:10.1128/MMBR.52.4.536-553.1988

465:Herskowitz I (December 1988).

419:

1:

1021:Fincham J RS, Day PR (1963).

412:

913:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002851

858:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003574

633:, InTech, DOI: 10.5772/56542

129:, the sac that contains the

7:

761:10.1128/EC.5.4.650-657.2006

400:

271:Henk et al. concluded that

39:ones, which are capable of

10:

1095:

990:10.1093/genetics/132.1.149

947:American Journal of Botany

239:is the major producer of

116:Saccharomyces cerevisiae

107:Saccharomyces cerevisiae

97:Saccharomyces cerevisiae

49:Saccharomyces cerevisiae

43:from a single organism.

1046:Genetics and Metabolism

315:

110:

81:Neurospora tetrasperma

661:10.1128/mBio.00234-11

367:figure, top of §

352:figure, top of §

339:figure, top of §

335:figure, top of §

312:

284:may be maintained in

263:Talaromyces marneffei

174:Aspergillus fumigatus

167:Aspergillus fumigatus

105:

63:Penicillium marneffei

53:Aspergillus fumigatus

318:The sexual cycle of

714:10.1038/nature07528

706:2009Natur.457..471O

296:, discussed above.

278:genetic variability

41:sexual reproduction

316:

231:Aspergillus flavus

111:

85:intratetrad mating

57:Aspergillus flavus

631:978-953-51-1197-9

302:Neurospora crassa

155:genetic diversity

69:Neurospora crassa

1086:

1058:

1057:

1041:

1035:

1034:

1018:

1012:

1011:

1001:

969:

963:

962:

942:

936:

935:

925:

915:

906:(10): e1002851.

890:

881:

880:

870:

860:

836:

830:

829:

789:

783:

782:

772:

740:

734:

733:

689:

683:

682:

672:

655:(6): e00234–11.

640:

634:

623:

617:

606:

600:

599:

589:

557:

551:

550:

514:

505:

504:

494:

462:

456:

455:

438:(6): 1020–1038.

423:

183:immunodeficiency

1094:

1093:

1089:

1088:

1087:

1085:

1084:

1083:

1064:

1063:

1062:

1061:

1042:

1038:

1023:Fungal Genetics

1019:

1015:

970:

966:

943:

939:

891:

884:

851:(8): e1003574.

837:

833:

790:

786:

749:Eukaryotic Cell

741:

737:

700:(7228): 471–4.

690:

686:

641:

637:

624:

620:

607:

603:

558:

554:

515:

508:

463:

459:

424:

420:

415:

407:Mating of yeast

403:

360:binucleate cell

305:

266:

234:

170:

100:

19:

12:

11:

5:

1092:

1082:

1081:

1076:

1060:

1059:

1036:

1013:

984:(1): 149–162.

964:

937:

882:

831:

810:10.3852/09-011

784:

735:

684:

635:

618:

615:978-0306472619

601:

552:

531:10.1038/ng1859

525:(9): 1077–81.

506:

471:Microbiol. Rev

457:

417:

416:

414:

411:

410:

409:

402:

399:

387:N. crassa

371:N. crassa

330:N. crassa

321:N. crassa

304:

300:Life cycle of

298:

280:is produced.

265:

261:Life cycle of

259:

233:

229:Life cycle of

227:

169:

165:Life cycle of

163:

99:

95:Life cycle of

93:

17:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1091:

1080:

1077:

1075:

1072:

1071:

1069:

1055:

1051:

1047:

1040:

1032:

1028:

1024:

1017:

1009:

1005:

1000:

995:

991:

987:

983:

979:

975:

968:

960:

956:

952:

948:

941:

933:

929:

924:

919:

914:

909:

905:

901:

897:

889:

887:

878:

874:

869:

864:

859:

854:

850:

846:

842:

835:

827:

823:

819:

815:

811:

807:

803:

799:

795:

788:

780:

776:

771:

766:

762:

758:

754:

750:

746:

739:

731:

727:

723:

719:

715:

711:

707:

703:

699:

695:

688:

680:

676:

671:

666:

662:

658:

654:

650:

646:

639:

632:

628:

622:

616:

612:

605:

597:

593:

588:

583:

579:

575:

572:(1): 121–31.

571:

567:

563:

556:

548:

544:

540:

536:

532:

528:

524:

520:

513:

511:

502:

498:

493:

488:

484:

480:

477:(4): 536–53.

476:

472:

468:

461:

453:

449:

445:

441:

437:

433:

429:

422:

418:

408:

405:

404:

398:

394:

390:

388:

384:

380:

376:

372:

368:

363:

361:

357:

353:

348:

342:

340:

336:

331:

327:

323:

322:

311:

307:

303:

297:

295:

291:

290:S. cerevisiae

287:

283:

279:

274:

269:

264:

258:

256:

251:

249:

245:

242:

238:

232:

226:

224:

219:

214:

212:

208:

207:cleistothecia

204:

200:

199:conidiophores

196:

192:

188:

184:

180:

176:

175:

168:

162:

160:

159:S. cerevisiae

156:

151:

150:S. cerevisiae

147:

146:S. cerevisiae

143:

142:S. cerevisiae

138:

136:

132:

128:

123:

122:S. cerevisiae

118:

117:

108:

104:

98:

92:

90:

86:

82:

77:

75:

71:

70:

65:

64:

59:

58:

54:

50:

44:

42:

38:

34:

30:

26:

23:

22:Heterothallic

16:

1074:Reproduction

1045:

1039:

1022:

1016:

981:

977:

967:

950:

946:

940:

903:

899:

848:

844:

834:

804:(3): 423–9.

801:

797:

787:

755:(4): 650–7.

752:

748:

738:

697:

693:

687:

652:

648:

638:

621:

604:

569:

565:

555:

522:

518:

474:

470:

460:

435:

431:

421:

395:

391:

386:

370:

364:

343:

329:

319:

317:

306:

301:

294:A. fumigatus

293:

289:

286:T. marneffei

285:

273:T. marneffei

272:

270:

267:

262:

254:

252:

241:carcinogenic

236:

235:

230:

222:

218:A. fumigatus

217:

215:

187:A. fumigatus

186:

178:

172:

171:

166:

158:

149:

145:

141:

139:

121:

114:

112:

106:

96:

80:

78:

73:

67:

61:

47:

45:

21:

20:

15:

953:: 573–577.

900:PLOS Pathog

845:PLOS Pathog

356:uninucleate

326:ascomycetes

223:S. cereviae

179:Aspergillus

37:homothallic

1068:Categories

1054:B00BXTC5BO

1031:B000W851KO

519:Nat. Genet

413:References

347:ascogonium

244:aflatoxins

211:ascospores

113:The yeast

798:Mycologia

566:Mol. Ecol

452:1010-061X

255:A. flavus

237:A. flavus

216:Although

89:automixis

74:N. crassa

1079:Mycology

978:Genetics

932:23055919

877:24009506

826:20648447

818:19537215

779:16607012

722:19043401

679:22108383

596:20002587

539:16892060

401:See also

248:pathogen

195:nitrogen

1008:1356883

999:1205113

923:3464222

868:3757046

770:1459663

730:4371721

702:Bibcode

670:3225970

587:3892377

501:3070323

383:Meiosis

375:meiosis

203:conidia

135:meiosis

25:species

1052:

1029:

1006:

996:

930:

920:

875:

865:

824:

816:

777:

767:

728:

720:

694:Nature

677:

667:

629:

613:

594:

584:

547:783720

545:

537:

499:

492:373162

489:

450:

191:carbon

131:tetrad

109:tetrad

822:S2CID

726:S2CID

543:S2CID

379:ascus

127:ascus

33:fungi

29:sexes

27:have

1050:ASIN

1027:ASIN

1004:PMID

928:PMID

873:PMID

814:PMID

775:PMID

718:PMID

675:PMID

649:mBio

627:ISBN

611:ISBN

592:PMID

535:PMID

497:PMID

448:ISSN

292:and

209:and

193:and

66:and

994:PMC

986:doi

982:132

955:doi

918:PMC

908:doi

863:PMC

853:doi

806:doi

802:101

765:PMC

757:doi

710:doi

698:457

665:PMC

657:doi

582:PMC

574:doi

527:doi

487:PMC

479:doi

440:doi

282:Sex

185:.

91:).

1070::

1002:.

992:.

980:.

976:.

951:34

949:.

926:.

916:.

902:.

898:.

885:^

871:.

861:.

847:.

843:.

820:.

812:.

800:.

796:.

773:.

763:.

751:.

747:.

724:.

716:.

708:.

696:.

673:.

663:.

651:.

647:.

590:.

580:.

570:19

568:.

564:.

541:.

533:.

523:38

521:.

509:^

495:.

485:.

475:52

473:.

469:.

446:.

436:25

434:.

430:.

381:.

328:,

213:.

161:.

87:,

60:,

55:,

51:,

1056:.

1033:.

1010:.

988::

961:.

957::

934:.

910::

904:8

879:.

855::

849:9

828:.

808::

781:.

759::

753:5

732:.

712::

704::

681:.

659::

653:2

598:.

576::

549:.

529::

503:.

481::

454:.

442::

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.