450:

system, all the

Chinese writing characters were organized by five different tones and according to rhyming, using a standard official book of Chinese rhymes. Two revolving tables were actually used in the process; one table that had official types from the book of rhymes, and the other which contained the most frequently used Chinese writing characters for quick selection. To make the entire process more efficient, each Chinese character was assigned a different number, so that when a number was called, that writing character would be selected. Rare and unusual characters that were not prescribed a number were simply crafted on the spot by wood-cutters when needed.

323:

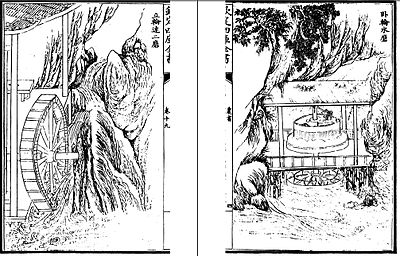

front of the bellows there are strong bamboo (springs) connected with it by ropes; this is what controls the motion of the fan of the bellows. Then in accordance with the turning of the (vertical) water-wheel, the lug fixed on the driving-shaft automatically presses upon and pushes the curved board (attached to the piston-rod), which correspondingly moves back (lit. inwards). When the lug has finally come down, the bamboo (springs) act on the bellows and restore it to its original position. In like manner, using one main drive it is possible to actuate several bellows (by lugs on the shaft), on the same principle as the water

226:

376:

317:

rotated by the force of the water. The upper one is connected by a driving-belt to a (smaller) wheel in front of it, which bears an eccentric lug (lit. oscillating rod). Then all as one, following the turning (of the driving wheel), the connecting-rod attached to the eccentric lug pushes and pulls the rocking roller, the levers to left and right of which assure the transmission of the motion to the piston-rod. Thus this is pushed back and forth, operating the furnace bellows far more quickly than would be possible with man-power.

593:(1644–1911), wooden movable type was used on a much wider scale than even the previous Ming period. It was officially sponsored by the imperial court at Beijing, yet was widespread amongst private printing companies. The creation of movable type writing fonts became a wise enterprise of investment, since they were commonly pawned, sold, or presented as gifts during the Qing period. In the sphere of the imperial court, the official Jin Jian (d. 1794) was placed in charge of printing at the Wuying Palace, where the

430:

367:

425:

piece. These separate characters are finished off with a knife on all four sides, and compared and tested till they are exactly the same height and size. Then the types are placed in the columns and bamboo strips which have been prepared are pressed in between them. After the types have all been set in the form, the spaces are filled in with wooden plugs, so that the type is perfectly firm and will not move. When the type is absolutely firm, the ink is smeared on and printing begins.

696:, etc. It listed and described many of the various foodstuffs and products of the many regions of China. The book outlined the use of not only agricultural tools, but food-processing, irrigation equipment, different types of fields, ceremonial vessels, various types of grain storage, carts, boats, mechanical devices, and textile machinery used in many applications. For example, one of the many devices described and illustrated in drawing is a large

44:

403:

394:

385:

358:

486:

658:

677:) written by Wang was the realm of Chinese agriculture. His book listed and described an enormous catalogue of agricultural tools and implements used in the past and in his own day. Furthermore, Wang incorporated a systematic usage of illustrated pictures in his book to accompany every piece of farming equipment described. Wang also created an agricultural

586:. In 1541, two different significant publications using wooden movable type were made under the sponsorship of two different princes; the Prince of Shu printing the large literary collection of the earlier Song dynasty poet Su Che, and the Prince of Yi printing a book written as a rebuttal against superstitions written by a Yuan dynasty era author.

709:

cultivation was more suitable for southern China. Furthermore, Wang used his treatise as a means to spread knowledge in support of certain agricultural practices or technologies found exclusively in either South or North that could benefit the other, if only they were more widely known, such as the southern hand-

449:

in the 11th century, but it was discarded because wood was judged to be an unsuitable material to use. Wang improved the earlier experimented process by adding the methods of specific type cutting and finishing, making the type case and revolving table that made the process more efficient. In Wang's

419:

printing type with earthenware frame in order to make whole blocks. Wang is best known for his usage of wooden movable type while he was a magistrate of Jingde in Anhui province from 1290 to 1301. His main contribution was improving the speed of typesetting with simple mechanical devices, along with

424:

Now, however, there is another method that is both more exact and more convenient. A compositor's form is made of wood, strips of bamboo are used to mark the lines and a block is engraved with characters. The block is then cut into squares with a small fine saw till each character forms a separate

322:

Another method is also used. At the end of the wooden (piston-)rod, about 3 ft long, which comes out from the front of the bellows, there is set up right a curved piece of wood shaped like the crescent of the new moon, and (all) this is suspended from above by a rope like those of a swing. Then in

316:

According to modern study (+1313!), leather bag bellows were used in olden times, but now they always use wooden fan (bellows). The design is as follows. A place beside a rushing torrent is selected, and a vertical shaft is set up in a framework with two horizontal wheels so that the lower one is

648:

There are notable differences between Wang's movable type process and Jin Jian's. Wang carved the written characters on wooden blocks and then sawed them apart, while Jin initiated the process by preparing type bodies before the characters were individually cut into types. For setting type, Wang

166:

of 1313 was a very important medieval treatise outlining the application and use of the various

Chinese sciences, technologies, and agricultural practices. From water-powered bellows to movable type printing, it is considered a descriptive masterpiece on contemporary medieval Chinese technology.

473:

In more recent times , type has also been made of tin by casting. It is strung on an iron wire, and thus made fast in the columns of the form, in order to print books with it. But none of this type took ink readily, and it made untidy printing in most cases. For that reason they were not used

453:

While printing new books, Wang described that the rectangular dimensions of each book needed to be determined in order to make the corrected size of the four-sided wooden block used in printing. Providing the necessary ink job was done by brush that was moved vertically in columns, while the

649:

employed a method of revolving tables where the type came to the workers, whereas Jin developed a system where the workers went to the organized type. Wang's frame was also added after the type had already been set, whereas Jin printed the ruled sheets and text separately on the same paper.

708:

historians, Wang also outlined the difference between the agricultural technology of

Northern China and that of Southern China. The main characteristic of agricultural technology of the north was technical applications fit for predominantly dryland cultivation, while intensified irrigation

194:

could help rural farmers maximize efficiency of producing yields and they could learn how to use various agricultural tools to aid their daily lives. However, it was not intended to be read by rural farmers (who were largely illiterate), but local officials who desired to research the best

513:

paper of Jingde City, which incorporated the use of 60,000 written characters organized on revolving tables. During the year of 1298, roughly one hundred copies of this were printed by wooden movable type in a month's time. Following in the footsteps of Wang, in 1322 the magistrate of

689:, the four seasons, twelve months, twenty-four solar terms, seventy-two five-day periods, with each sequence of agricultural tasks and the natural phenomena which signal for their necessity, stellar configurations, phenology, and the sequence of agricultural production.

292:

wrote that a planned, artificial lake had been constructed in the Yuan-Jia reign period (424–429) for the sole purpose of powering water wheels aiding the smelting and casting processes of the

Chinese iron industry. The 5th-century text

534:

used bronze movable type in 1490. Although metal movable type became available in China during the Ming period, wooden movable type persisted in common use even until the 19th century. After that point, the

European

582:. There were many books from a wide variety of subjects published in wooden movable type during the Ming period, including novels, art, science and technology, family registers, and local

522:

province, named Ma

Chengde, printed Confucian classics with movable type of 100,000 written characters on needed revolving tables. The process of metal movable type was also developed in

162:. Although the title describes the main focus of the work, it incorporated much more information on a wide variety of subjects that was not limited to the scope of agriculture. Wang's

308:

Although Du Shi was the first to apply water power to bellows in metallurgy, the first drawn and printed illustration of its operation with water power came in 1313, with Wang Zhen's

148:

for Jingde, Anhui province, where he was a pioneer of the use of wooden movable type printing. The wooden movable type was described in Wang Zhen's publication of 1313, known as the

597:

had 253,000 wooden movable type characters crafted in the year of 1733. Jin Jian, the official in charge of this project, provided elaborate detail on the printing process in his

186:

was a period of high

Chinese culture and relative economic and agricultural stability, the Yuan dynasty thoroughly damaged the economic and agricultural base of China during the

482:

process. Although unsuccessful in Wang's time, the bronze metal type of Hua Sui in the late 15th century would be used for centuries in China, up until the late 19th century.

284:. After Du Shi, Chinese in subsequent dynastic periods continued the use of water power to operate the bellows of the blast furnace. In the 5th century text of the

124:

treatise was also one of the most advanced of its day, covering a wide range of equipment and technologies available in the late 13th and early 14th century.

420:

the complex, systematic arrangement of wooden movable types. Wang summarized the process of making wooden movable type as described in the passage below:

692:

Amongst the various contemporary agricultural practices mentioned in the Nong Shu, Wang listed and described the use of ploughing, sowing, irrigation,

509:, his innovation of wooden movable type soon became popularly used in the region of Anhui. Wang's wooden movable type was used to print the local

100:

117:

558:, local government offices, by wealthy local patrons of printing, and the large Chinese commercial printers located in the cities of

335:, Wang Zhen's blowing engine is one of "the two machines of the Middle Ages which lie most directly in the line of ancestry of the

1232:

704:, with an enormous rotating geared wheel engaging the toothed gears of eight different mills surrounding it. Of great interest to

1298:

981:

543:

in the 15th century became the mainstay and standard in China and for the most part the global community until the advent of

554:

With movable type printing during the Ming dynasty of the 14th to 16th centuries, however, it was known to be used by local

312:. Wang explained the methods used for the water-powered blast-furnace in previous times and in his era of the 14th century:

601:(Imperial Printing Office Manual for Movable Type). In nineteen different sections, he provided detailed description for:

794:

1313:

1273:

1263:

1308:

1323:

178:

in China looking for means to improve their economic livelihoods in the face of poverty and oppression during the

1278:

1268:

70:

1328:

1241:

969:

Science and

Civilisation in China, Volume 4: Physics and Physical Technology (Part II: Mechanical Technology)

809:

478:

Thus, Chinese metal type of the 13th century using tin was unsuccessful because it was incompatible with the

187:

62:

1288:

967:

1318:

1293:

973:

20:

1303:

1283:

103:

1290–1333) was a

Chinese agronomist, inventor, mechanical engineer, politician, and writer of the

19:

This article is about Wang Zhen, agronomist and inventor. For other people with the same name, see

674:

829:

206:. However, this was only slightly larger than the early medieval Chinese agricultural treatise

1258:

834:

461:

pioneered bronze-type printing in China in 1490, Wang had experimented with printing using

195:

agricultural methods currently available that the peasants otherwise would know little of.

225:

8:

526:

Korea by the 13th century, while metal movable type was not pioneered in China until the

212:

written by Jia Sixia in 535, which had slightly over 100,000 written

Chinese characters.

1229:

819:

799:

540:

506:

494:

375:

203:

977:

594:

686:

548:

544:

415:

In improving movable type printing, Wang mentioned an alternative method of baking

174:

for many practical reasons, but also as a means to aid and support destitute rural

202:

was an incredibly long book even for its own time, which had over 110,000 written

1236:

697:

31:

454:

impression on paper the columns had to be rubbed with brush from top to bottom.

963:

814:

682:

536:

523:

429:

332:

281:

88:

36:

366:

1252:

710:

662:

490:

262:

590:

527:

434:

336:

298:

238:

208:

183:

179:

121:

111:

104:

27:

748:

Bamboos and miscellaneous (including ramie, cotton, tea, dye plants, etc.)

297:

mentions the use of rushing river water to power waterwheels, as does the

693:

324:

246:

824:

705:

348:

340:

254:

230:

145:

567:

555:

510:

416:

402:

393:

384:

357:

344:

266:

250:

47:

43:

713:

used for weeding in the south, yet virtually unknown in the north.

678:

583:

571:

519:

446:

270:

133:

114:

1086:

1084:

1041:

1039:

465:, a metal favored for its low melting point while casting. In the

437:

characters arranged primarily by rhyming scheme, from Wang Zhen's

804:

575:

559:

531:

515:

458:

289:

277:

258:

141:

1156:

1081:

1072:

1036:

1027:

579:

563:

273:

175:

78:

1122:

1120:

1118:

1108:

1106:

1104:

1102:

1100:

1098:

1096:

1065:

1063:

1053:

1051:

1020:

1018:

1016:

1014:

1012:

1010:

1008:

1006:

1004:

1002:

917:

485:

1183:

1176:

1174:

1172:

1170:

1168:

1147:

949:

947:

868:

866:

137:

892:

890:

888:

886:

884:

882:

880:

878:

856:

854:

657:

1115:

1093:

1060:

1048:

999:

990:

908:

728:

Comprehensive prescriptions for agriculture and sericulture

445:

Wooden movable type had been used and experimented with by

108:

1165:

1138:

1129:

944:

926:

863:

899:

875:

851:

479:

462:

1230:

Movable type and illustration of Wang Zhen's wooden type

269:. This was recorded in AD 31, an innovation of the

701:

107:(1271–1368). He was one of the early innovators of the

935:

136:

province, and spent many years as an official of both

681:

diagram in the form of a circle, which included the

249:(202 BC – AD 220) were the first to apply

1217:

Science and Civilization in China: Volume 6, Part 2

1210:

Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 1

1203:

Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 2

1250:

758:Illustrated Treatise on Agricultural Implements

776:Irrigation equipment, water-powered mills, etc.

410:

229:An illustration of furnace bellows operated by

739:Cereals (including legumes, hemp, and sesame)

153:

215:

770:Food-processing equipment and grain storage

433:A revolving table typecase with individual

327:. This is also very convenient and quick...

656:

484:

428:

237:, by Wang Zhen, 1313, during the Mongol

224:

220:

42:

962:

144:provinces. From 1290 to 1301, he was a

93:

1251:

716:

1162:Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 195-196.

1090:Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 208-209.

1078:Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 216-217.

1033:Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 206-207.

923:Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 371-371.

13:

1045:Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 205-206

795:History of typography in East Asia

782:Sericulture and textile production

599:Wu Ying Tian Ju Zhen Ban Cheng Shi

14:

1340:

1223:

1189:Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 61-62.

1153:Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 53-55.

127:

700:operated by the motive power of

401:

392:

383:

374:

365:

356:

1126:Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 211.

1112:Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 209.

1024:Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 208.

996:Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 203.

956:

953:Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 376.

941:Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 371.

932:Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 373.

872:Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 206.

736:Treatise on the Hundred Grains

1180:Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 61.

1144:Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 92.

1135:Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 75.

1069:Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 217

1057:Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 207

914:Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 370

905:Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 56.

896:Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 60.

860:Needham, Volume 6, Part 2, 59.

742:Cucurbits and green vegetables

652:

182:period. Although the previous

83:

74:

66:

1:

1242:Wang Zhen at Chinaculture.org

840:

810:History of western typography

773:Ceremonial vessels, transport

505:was mostly printed by use of

1299:Chinese mechanical engineers

845:

779:Special implements for wheat

617:strips in variable thickness

411:Wang's movable type printing

257:) in working the inflatable

190:. Hence, a book such as the

7:

1219:. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

1212:. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

1205:. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

788:

644:and a schedule for rotation

539:machine first pioneered by

493:(868), the oldest existent

170:Wang wrote the masterpiece

10:

1345:

1195:

974:Cambridge University Press

629:page and column rule forms

25:

21:Wang Zhen (disambiguation)

18:

694:cultivation of mulberries

216:Technological innovations

154:

1314:Scientists from Shandong

1274:14th-century agronomists

1264:13th-century agronomists

1215:Needham, Joseph (1986).

1208:Needham, Joseph (1986).

1201:Needham, Joseph (1986).

698:mechanical milling plant

641:distribution of the type

1309:Engineers from Shandong

303:Yuan-he Jun Xian Tu Chi

245:The Chinese during the

1279:14th-century inventors

1269:13th-century inventors

830:History of Agriculture

767:Wicker and basket ware

669:The main focus of the

666:

498:

476:

442:

427:

329:

319:

301:geography text of the

242:

132:Wang Zhen was born in

55:

660:

488:

471:

457:Two centuries before

432:

422:

320:

314:

228:

221:Water-powered bellows

46:

1329:Yuan dynasty writers

1235:2 April 2007 at the

835:Agriculture in China

530:(1368–1644) printer

188:Song–Yuan transition

16:Officer and inventor

1324:Writers from Tai'an

1289:Chinese agronomists

160:Book of Agriculture

71:traditional Chinese

976:. pp. 380–2.

820:Johannes Gutenberg

800:Woodblock printing

764:Agricultural tools

667:

541:Johannes Gutenberg

507:woodblock printing

499:

497:book in the world.

443:

305:, written in 814.

243:

204:Chinese characters

120:. His illustrated

63:simplified Chinese

56:

1319:Technical writers

1294:Chinese inventors

983:978-0-521-05803-2

611:making type cases

595:Yongzheng Emperor

495:woodblock printed

441:, published 1313.

1336:

1304:Chinese printers

1284:Agriculturalists

1190:

1187:

1181:

1178:

1163:

1160:

1154:

1151:

1145:

1142:

1136:

1133:

1127:

1124:

1113:

1110:

1091:

1088:

1079:

1076:

1070:

1067:

1058:

1055:

1046:

1043:

1034:

1031:

1025:

1022:

997:

994:

988:

987:

960:

954:

951:

942:

939:

933:

930:

924:

921:

915:

912:

906:

903:

897:

894:

873:

870:

861:

858:

687:Earthly Branches

632:setting the text

608:cutting the type

549:computer printer

545:digital printing

501:Although Wang's

405:

396:

387:

378:

369:

360:

351:a century later.

157:

156:

102:

97:

85:

76:

68:

1344:

1343:

1339:

1338:

1337:

1335:

1334:

1333:

1249:

1248:

1237:Wayback Machine

1226:

1198:

1193:

1188:

1184:

1179:

1166:

1161:

1157:

1152:

1148:

1143:

1139:

1134:

1130:

1125:

1116:

1111:

1094:

1089:

1082:

1077:

1073:

1068:

1061:

1056:

1049:

1044:

1037:

1032:

1028:

1023:

1000:

995:

991:

984:

964:Needham, Joseph

961:

957:

952:

945:

940:

936:

931:

927:

922:

918:

913:

909:

904:

900:

895:

876:

871:

864:

859:

852:

848:

843:

791:

754:Chapters 11–22

722:

655:

547:and the modern

413:

406:

397:

388:

379:

370:

361:

223:

218:

130:

50:in Wang Zhen's

41:

24:

17:

12:

11:

5:

1342:

1332:

1331:

1326:

1321:

1316:

1311:

1306:

1301:

1296:

1291:

1286:

1281:

1276:

1271:

1266:

1261:

1245:

1244:

1239:

1225:

1224:External links

1222:

1221:

1220:

1213:

1206:

1197:

1194:

1192:

1191:

1182:

1164:

1155:

1146:

1137:

1128:

1114:

1092:

1080:

1071:

1059:

1047:

1035:

1026:

998:

989:

982:

955:

943:

934:

925:

916:

907:

898:

874:

862:

849:

847:

844:

842:

839:

838:

837:

832:

827:

822:

817:

815:Printing Press

812:

807:

802:

797:

790:

787:

786:

785:

784:

783:

780:

777:

774:

771:

768:

765:

762:

752:

751:

750:

749:

746:

743:

740:

732:Chapters 7–10

730:

729:

721:

715:

683:Heavenly Stems

661:A modern disc

654:

651:

646:

645:

642:

639:

636:

633:

630:

627:

624:

623:center columns

621:

618:

615:

612:

609:

606:

537:printing press

469:, Wang wrote:

412:

409:

408:

407:

400:

398:

391:

389:

382:

380:

373:

371:

364:

362:

355:

333:Joseph Needham

253:power (i.e. a

222:

219:

217:

214:

129:

128:Life and works

126:

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1341:

1330:

1327:

1325:

1322:

1320:

1317:

1315:

1312:

1310:

1307:

1305:

1302:

1300:

1297:

1295:

1292:

1290:

1287:

1285:

1282:

1280:

1277:

1275:

1272:

1270:

1267:

1265:

1262:

1260:

1257:

1256:

1254:

1247:

1243:

1240:

1238:

1234:

1231:

1228:

1227:

1218:

1214:

1211:

1207:

1204:

1200:

1199:

1186:

1177:

1175:

1173:

1171:

1169:

1159:

1150:

1141:

1132:

1123:

1121:

1119:

1109:

1107:

1105:

1103:

1101:

1099:

1097:

1087:

1085:

1075:

1066:

1064:

1054:

1052:

1042:

1040:

1030:

1021:

1019:

1017:

1015:

1013:

1011:

1009:

1007:

1005:

1003:

993:

985:

979:

975:

971:

970:

965:

959:

950:

948:

938:

929:

920:

911:

902:

893:

891:

889:

887:

885:

883:

881:

879:

869:

867:

857:

855:

850:

836:

833:

831:

828:

826:

823:

821:

818:

816:

813:

811:

808:

806:

803:

801:

798:

796:

793:

792:

781:

778:

775:

772:

769:

766:

763:

761:Field systems

760:

759:

757:

756:

755:

747:

744:

741:

738:

737:

735:

734:

733:

727:

726:

725:

724:Chapters 1–6

719:

714:

712:

707:

703:

699:

695:

690:

688:

684:

680:

676:

672:

664:

659:

650:

643:

640:

637:

634:

631:

628:

626:sorting trays

625:

622:

619:

616:

613:

610:

607:

604:

603:

602:

600:

596:

592:

587:

585:

581:

577:

573:

569:

565:

561:

557:

552:

550:

546:

542:

538:

533:

529:

525:

521:

517:

512:

508:

504:

496:

492:

491:Diamond Sutra

487:

483:

481:

475:

470:

468:

464:

460:

455:

451:

448:

440:

436:

431:

426:

421:

418:

404:

399:

395:

390:

386:

381:

377:

372:

368:

363:

359:

354:

353:

352:

350:

346:

343:" along with

342:

338:

334:

331:According to

328:

326:

318:

313:

311:

306:

304:

300:

296:

295:Shui Jing Zhu

291:

288:, its author

287:

283:

279:

275:

272:

268:

264:

263:blast furnace

260:

256:

252:

248:

240:

236:

232:

227:

213:

211:

210:

205:

201:

196:

193:

189:

185:

181:

177:

173:

168:

165:

161:

151:

147:

143:

139:

135:

125:

123:

119:

116:

113:

110:

106:

98:

96:

90:

86:

80:

72:

64:

60:

53:

49:

45:

39:

38:

33:

29:

22:

1246:

1216:

1209:

1202:

1185:

1158:

1149:

1140:

1131:

1074:

1029:

992:

968:

958:

937:

928:

919:

910:

901:

753:

731:

723:

717:

691:

670:

668:

647:

598:

591:Qing dynasty

588:

553:

528:Ming dynasty

502:

500:

489:The Chinese

477:

472:

466:

456:

452:

444:

438:

435:movable type

423:

414:

347:'s slot-rod

337:steam-engine

330:

325:trip-hammers

321:

315:

309:

307:

302:

299:Tang dynasty

294:

285:

265:in creating

244:

239:Yuan dynasty

234:

209:Qimin Yaoshu

207:

199:

197:

191:

184:Song dynasty

171:

169:

163:

159:

149:

131:

122:agricultural

112:movable type

105:Yuan dynasty

94:

92:

82:

58:

57:

51:

35:

28:Chinese name

1259:1333 deaths

679:calendrical

653:Agriculture

589:During the

286:Wu Chang Ji

247:Han dynasty

233:, from the

231:waterwheels

54:, volume 19

32:family name

1253:Categories

841:References

825:Xu Guangqi

706:sinologist

614:form trays

349:force pump

341:locomotive

255:waterwheel

146:magistrate

118:technology

89:Wade–Giles

48:Watermills

846:Citations

605:type body

568:Changzhou

556:academies

511:gazetteer

417:porcelain

345:Al-Jazari

267:cast iron

251:hydraulic

95:Wang Chen

84:Wáng Zhēn

59:Wang Zhen

1233:Archived

966:(1965).

789:See also

720:chapters

718:Nong Shu

671:Nong Shu

638:printing

635:proofing

584:gazettes

572:Hangzhou

520:Zhejiang

503:Nong Shu

467:Nong Shu

447:Bi Sheng

439:Nong Shu

339:and the

310:Nong Shu

271:engineer

235:Nong Shu

200:Nong Shu

192:Nong Shu

172:Nong Shu

164:Nong Shu

150:Nong Shu

134:Shandong

115:printing

52:Nong Shu

26:In this

1196:Sources

805:Hua Sui

675:农书 / 農書

576:Wenzhou

560:Nanjing

532:Hua Sui

516:Fenghua

459:Hua Sui

290:Pi Ling

282:Nanyang

278:Prefect

261:of the

259:bellows

176:farmers

142:Jiangxi

980:

745:Fruits

711:harrow

685:, the

663:harrow

620:blanks

580:Fuzhou

578:, and

564:Suzhou

524:Joseon

480:inking

274:Du Shi

158:), or

109:wooden

91::

81::

79:pinyin

73::

65::

30:, the

474:long.

138:Anhui

978:ISBN

702:oxen

198:The

180:Yuan

140:and

37:Wang

463:tin

280:of

101:fl.

34:is

1255::

1167:^

1117:^

1095:^

1083:^

1062:^

1050:^

1038:^

1001:^

972:.

946:^

877:^

865:^

853:^

574:,

570:,

566:,

562:,

551:.

518:,

276:,

155:農書

99:,

87:;

77:;

75:王禎

69:;

67:王祯

986:.

673:(

665:.

241:.

152:(

61:(

40:.

23:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.