520:. AD 54–68). At the same period, some workshops experimented briefly with a marbled red-and-yellow slip, a variant that never became generally popular. Early production of plain forms in South Gaul initially followed the Italian models closely, and even the characteristic Arretine decorated form, Dragendorff 11, was made. But many new shapes quickly evolved, and by the second half of the 1st century AD, when Italian sigillata was no longer influential, South Gaulish samian had created its own characteristic repertoire of forms. The two principal decorated forms were Dragendorff 30, a deep, cylindrical bowl, and Dragendorff 29, a carinated ('keeled') shallow bowl with a marked angle, emphasised by a moulding, mid-way down the profile. The footring is low, and potters' stamps are usually bowl-maker's marks placed in the interior base, so that vessels made from the same, or parallel, moulds may bear different names. The rim of the 29, small and upright in early examples of the form, but much deeper and more everted by the 70s of the 1st century, is finished with rouletted decoration, and the relief-decorated surfaces necessarily fall into two narrow zones. These were usually decorated with floral and foliate designs of wreaths and scrolls at first: the Dr.29 resting on its rim illustrated in the lead section of this article is an early example, less angular than the developed form of the 60s and 70s, with decoration consisting of simple, very elegant leaf-scrolls. Small human and animal figures, and more complex designs set out in separate panels, became more popular by the 70s of the 1st century. Larger human and animal figures could be used on the Dr.30 vessels, but while many of these have great charm, South Gaulish craftsmen never achieved, and perhaps never aspired to, the Classical naturalism of some of their Italian counterparts.

290:

substituted in iron. The two crystal populations are homogenously dispersed within the matrix. The colour of haematite depends on the crystal size. Large crystals of this mineral are black but as the size decreases to sub-micron the colour shifts to red. The fraction of aluminium has a similar effect. It was formerly thought that the difference between 'red' and 'black' samian was due to the presence (black) or absence (red) of reducing gases from the kiln and that the construction of the kiln was so arranged as to prevent the reducing gases from the fuel from coming into contact with the pottery. The presence of iron oxides in the clay/slip was thought to be reflected in the colour according to the oxidation state of the iron (Fe for the red and Fe for the black, the latter produced by the reducing gases coming into contact with the pottery during firing). It now appears as a result of this recent work that this is not the case and that the colour of the glossy slip is in fact due to no more than the crystal size of the minerals dispersed within the matrix glass.

443:

338:

began to expand in the middle of the 1st century BC, and examples were imported into Italy. Relief-decorated cups, some in lead-glazed wares, were produced at several eastern centres, and undoubtedly played a part in the technical and stylistic evolution of decorated

Arretine, but Megarian bowls, made chiefly in Greece and Asia Minor, are usually seen as the most direct inspiration. These are small, hemispherical bowls without foot-rings, and their decoration is frequently very reminiscent of contemporary silver bowls, with formalised, radiating patterns of leaves and flowers. The crisp and precisely profiled forms of the plain dishes and cups were also part of a natural evolution of taste and fashion in the Mediterranean world of the 1st century BC.

176:), is always used for both Italian and Gaulish products. Nomenclature has to be established at an early stage of research into a subject, and antiquarians of the 18th and 19th centuries often used terms that we would not choose today, but as long as their meaning is clear and well-established, this does not matter, and detailed study of the history of the terminology is really a side-issue that is of academic interest only. Scholars writing in English now often use "red gloss wares" or "red slip wares", both to avoid these issues of definition, and also because many other wares of the Roman period share aspects of technique with the traditional sigillata fabrics.

697:

Some of the Dr.37 bowls, for example those with the workshop stamp of Ianus, bear comparison with

Central Gaulish products of the same date: others are less successful. But the real strength of the Rheinzabern industry lay in its extensive production of good-quality samian cups, beakers, flagons and vases, many imaginatively decorated with barbotine designs or in the 'cut-glass' incised technique. Ludowici created his own type-series, which sometimes overlaps with those of other sigillata specialists. Ludowici's types use combinations of upper- and lower-case letters rather than simple numbers, the first letter referring to the general shape, such as 'T' for

926:

950:

387:(stamps) used making the moulds of human and animal figures to be fairly large, often about 5–6 cm high, and the modelling is frequently very accomplished indeed, attracting the interest of modern art-historians as well as archaeologists. Major workshops, such as those of M.Perennius Tigranus, P. Cornelius and Cn. Ateius, stamped their products, and the names of the factory-owners and of the workers within the factories, which often appear on completed bowls and on plain wares, have been extensively studied, as have the forms of the vessels, and the details of their dating and distribution.

890:

299:

485:, from the late 1st century BC: of these, La Graufesenque, near Millau, was the principal producer and exporter. Although the establishment of sigillata potteries in Gaul may well have arisen initially to meet local demand and to undercut the prices of imported Italian goods, they became enormously successful in their own right, and by the later 1st century AD, South Gaulish samian was being exported not only to other provinces in the north-west of the Empire, but also to Italy and other regions of the Mediterranean, North Africa and even the eastern Empire. One of the finds in the ruins of

962:

604:

600:, food-preparation bowls with a gritted interior surface, were also made in Central Gaulish samian fabric in the second half of the 2nd century (Dr.45). There is a small sub-class of Central Gaulish samian ware with a glossy black slip, though the dividing line between black terra sigillata and other fine black-gloss wares, which were also manufactured in the area, is sometimes hazy. When a vessel is a classic samian form and decorated in relief in the style of a known samian potter, but finished with black slip rather than a red one, it may be classed as black samian.

497:

286:(big kiln) at La Graufesenque, which was in use in the late 1st and early 2nd century, confirms the scale of the industry. It is a rectangular stone-built structure measuring 11.3 m. by 6.8 m. externally, with an original height estimated at 7 metres. With up to nine 'storeys' within (dismantled after each firing), formed of tile floors and vertical columns in the form of clay pipes or tubes, which also served to conduct the heat, it has been estimated that it was capable of firing 30,000–40,000 vessels at a time, at a temperature of around 1000 °C.

180:

117:

914:

20:

938:

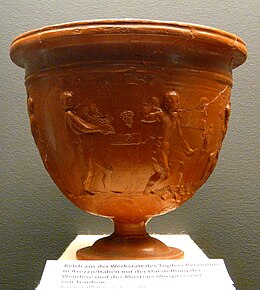

830:

234:: a potter's stamp or moulded decoration provides even more precise evidence. The classic guide by Oswald and Pryce, published in 1920 set out many of the principles, but the literature on the subject goes back into the 19th century, and is now extremely voluminous, including many monographs on specific regions, as well as excavation reports on important sites that have produced significant assemblages of sigillata wares, and articles in learned journals, some of which are dedicated to Roman pottery studies.

1104:, Poland, and processed into small tablets. He promoted it as a panacea effective against every type of poison and several diseases, including plague. Berthold invited authorities to test it themselves. In two cases, physicians, princes and town leaders conducted trials involving dogs who were either given poison followed by the antidote or poison alone; the dogs who got the antidote lived and the dogs who got the poison alone died. In 1581, a prince tested the antidote on a condemned criminal, who survived.

902:

557:

458:

524:

238:

347:

866:

634:

221:/jugs that cannot be made in a single mould because they have a swelling profile that tapers inwards from the point of greatest diameter. Some large flagons were made at La Graufesenque by making the lower and upper bowl-shaped portions in moulds, and then joining these and adding the neck. Obviously the open forms, namely bowls that could be formed in, and extracted from, a single mould, were quicker and simpler to make.}} Study of the characteristic decorative

862:, the eastern Mediterranean and Egypt. Over the long period of production, there was obviously much change and evolution in both forms and fabrics. Both Italian and Gaulish plain forms influenced ARS in the 1st and 2nd centuries (for example, Hayes Form 2, the cup or dish with an outcurved rim decorated with barbotine leaves, is a direct copy of the samian forms Dr.35 and 36, made in South and Central Gaul), but over time a distinctive ARS repertoire developed.

209:. The mould was therefore decorated on its interior surface with a full decorative design of impressed, intaglio (hollowed) motifs that would appear in low relief on any bowl formed in it. As the bowl dried, the shrinkage was sufficient for it to be withdrawn from the mould, in order to carry out any finishing work, which might include the addition of foot-rings, the shaping and finishing of rims, and in all cases the application of the slip.

32:

391:

311:

257:-decorated wares echo the general traditions of Graeco-Roman decorative arts, with depictions of deities, references to myths and legends, and popular themes such as hunting and erotic scenes. Individual figure-types, like the vessel-shapes, have been classified, and in many cases they may be linked with specific potters or workshops. Some of the decoration relates to contemporary architectural ornament, with

592:, it was by far the most common type of fine tableware, plain and decorated, in use during the 2nd century AD. The quality of the ware and the slip is usually excellent, and some of the products of Les Martres-de-Veyre, in particular, are outstanding, with a lustrous slip and a very hard, dense body. The surface colour tends towards a more orange-red hue than the typical South Gaulish slips.

1148:, though of course the pottery known as samian ware to present-day archaeologists has nothing to do with that region. The modern parallel of the English term 'china' may be an apt one: 'china' refers to a class of ceramic that no longer has any direct connection with the country, China, but it was originally developed as part of the European attempts to imitate imported

103:, mixed as a very thin liquid slip and settled to separate out only the finest particles to be used as terra sigillata. When applied to unfired clay surfaces, "terra sig" can be polished with a soft cloth or brush to achieve a shine ranging from a smooth silky lustre to a high gloss. The surface of ancient terra sigillata vessels did not require this

326:, and later their regional variants made in Italy, involved the preparation of a very fine clay body covered with a slip that fired to a glossy surface without the need for any polishing or burnishing. Greek painted wares also involved the precise understanding and control of firing conditions to achieve the contrasts of black and red.

779:. By the early 2nd century AD, when Gaulish samian was completely dominating the markets in the Northern provinces, the eastern sigillatas were themselves beginning to be displaced by the rising importance of African Red Slip wares in the Mediterranean and the Eastern Empire. In the fourth century AD,

362:

27 BC – AD 14), this tableware, with its precise forms, shiny surface, and, on the decorated vessels, its visual introduction to

Classical art and mythology, must have deeply impressed some inhabitants of the new northern provinces of the Empire. Certainly it epitomised certain aspects of Roman

873:

There was a wide range of dishes and bowls, many with rouletted or stamped decoration, and closed forms such as tall ovoid flagons with appliqué ornament (Hayes Form 171). The ambitious large rectangular dishes with relief decoration in the centre and on the wide rims (Hayes Form 56), were clearly

616:

relief, with appliqué motifs, and a class usually referred to as 'cut-glass' decoration, with geometric patterns cut into the surface of the vessel before slipping and firing. Two standard 'plain' types made in considerable numbers in

Central Gaul also included barbotine decoration, Dr.35 and 36, a

536:

such as forms Déchelette 67 and Knorr 78 were also made in South Gaul, as were occasional 'one-off' or very ambitious mould-made vessels, such as large thin-walled flagons and flasks. But the mass of South

Gaulish samian found on Roman sites of the 1st century AD consists of plain dishes, bowls and

281:

in southern Gaul, documentary evidence in the form of lists or tallies apparently fired with single kiln-loads, giving potters' names and numbers of pots have long been known, and they suggest very large loads of 25,000–30,000 vessels. Though not all the kilns at this, or other, manufacturing sites

722:

In the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire, there had been several industries making fine red tablewares with smooth, glossy-slipped surfaces since about the middle of the 2nd century BC, well before the rise of the

Italian sigillata workshops. By the 1st century BC, their forms often paralleled

692:

The Trier potteries evidently began to make samian vessels around the beginning of the 2nd century AD, and were still active until the middle of the 3rd century. The styles and the potters have been divided by scholars into two main phases, Werkstatten I and II. Some of the later mould-made Dr.37

620:

During the second half of the 2nd century, some Lezoux workshops making relief-decorated bowls, above all that of

Cinnamus, dominated the market with their large production. The wares of Cinnamus, Paternus, Divixtus, Doeccus, Advocisus, Albucius and some others often included large, easily legible

433:

of vessel forms, bringing earlier work on the respective topics up to date. Catalogues of the punch motives and the workshops of

Arretine Sigillata were published in 2004 and 2009, respectively, and a catalogue on the known appliqué motifs appeared in 2024. As with all ancient pottery studies, each

337:

continued this technological tradition, though painted decoration gave way to simpler stamped motifs and in some cases, to applied motifs moulded in relief. The tradition of decorating entire vessels in low relief was also well established in Greece and Asia Minor by the time the

Arretine industry

74:

ranging from a soft lustre to a brilliant glaze-like shine, in a characteristic colour range from pale orange to bright red; they were produced in standard shapes and sizes and were manufactured on an industrial scale and widely exported. The sigillata industries grew up in areas where there were

696:

The

Rheinzabern kilns and their products have been studied since Wilhelm Ludowici (1855–1929) began to excavate there in 1901, and to publish his results in a series of detailed reports. Rheinzabern produced both decorated and plain forms for around a century from the middle of the 2nd century.

424:

The first published study of Arretine ware was that of Fabroni in 1841, and by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, German scholars in particular had made great advances in systematically studying and understanding both Arretine ware and the Gaulish samian that occurred on Roman military sites

289:

A 2005 work has shown that the slip is a matrix of mainly silicon and aluminium oxides, within which are suspended sub-microscopic crystals of haematite and corundum. The matrix itself does not contain any metallic ions, the haematite is substituted in aluminium and titanium while the corundum is

171:

Whereas Anthony King's definition, following the more usual practice among Roman pottery specialists, makes no mention of decoration, but states that terra sigillata is 'alternatively known as samian ware'. However, 'samian ware' is normally used only to refer to the sub-class of terra sigillata

1046:

Terra sigillata is usually brushed or sprayed in thin layers onto dry or almost dry unfired ware. The ware is then burnished with a soft cloth before the water in the terra sigillata soaks into the porous body or with a hard, smooth-surfaced object . The burnished ware is fired, often to a lower

1042:

or aggregates. For undisturbed deflocculated slip settling in a transparent container, these layers are usually visible within 24 hours. The top layer is water, the center layer is the terra sigillata and the bottom layer is the sludge. Siphoning off the middle layers of "sig" which contain the

704:

In general, the products of the East Gaulish industries moved away from the early imperial Mediterranean tradition of intricately profiled dishes and cups, and ornamented bowls made in moulds, and converged with the later Roman local traditions of pottery-making in the northern provinces, using

837:

African red slip ware (ARS) was the final development of terra sigillata. While the products of the Italian and Gaulish red-gloss industries flourished and were exported from their places of manufacture for at most a century or two each, ARS production continued for more than 500 years. The

531:

In the last two decades of the 1st century, the Dragendorff 37, a deep, rounded vessel with a plain upright rim, overtook the 29 in popularity. This simple shape remained the standard Gaulish samian relief-decorated form, from all Gaulish manufacturing regions, for more than a century. Small

269:

and the like. While the decoration of Arretine ware is often highly naturalistic in style, and is closely comparable with silver tableware of the same period, the designs on the Gaulish products, made by provincial artisans adopting Classical subjects, are intriguing for their expression of

160:. These high-quality tablewares were particularly popular and widespread in the Western Roman Empire from about 50 BC to the early 3rd century AD. Definitions of 'TS' have grown up from the earliest days of antiquarian studies, and are far from consistent; one survey of Classical art says:

611:

Though the Central Gaulish forms continued and built upon the South Gaulish traditions, the decoration of the principal decorated forms, Dr.30 and Dr.37, was distinctive. New human and animal figure-types appeared, generally modelled with greater realism and sophistication than those of La

107:

or polishing. Burnishing was a technique used on some wares in the Roman period, but terra sigillata was not one of them. The polished surface can only be retained if fired within the low-fire range and will lose its shine if fired higher, but can still display an appealing silky quality.

709:

ware, decorated with all-over patterns of small stamps, was made in the area east of Rheims and quite widely traded. Argonne ware was essentially still a type of sigillata, and the most characteristic form is a small, sturdy Dr.37 bowl. Small, localised attempts to make conventional

358:(Tuscany) a little before the middle of the 1st century BC. The industry expanded rapidly in a period when Roman political and military influence was spreading far beyond Italy: for the inhabitants of the first provinces of the Roman Empire in the reign of the Emperor Augustus (

588:(AD 98–117), and the beginning of a decline in the South Gaulish export trade, that Central Gaulish samian ware became important outside its own region. Though it never achieved the extensive geographical distribution of the South Gaulish factories, in the provinces of Gaul and

187:

Italian and Gaulish TS vessels were made in standardised shapes constituting services of matching dishes, bowls and serving vessels. These changed and evolved over time, and have been very minutely classified; the first major scheme, by the German classical archaeologist

874:

inspired by decorated silver platters of the 4th century, which were made in rectangular and polygonal shapes as well as in the traditional circular form. Decorative motifs reflected not only the Graeco-Roman traditions of the Mediterranean, but eventually the rise of

595:

Vessel-forms that had been made in South Gaul continued to be produced, though as the decades passed, they evolved and changed with the normal shifts of fashion, and some new shapes were created, such as the plain bowl with a horizontal flange below the rim, Dr.38.

705:

free-thrown, rounded forms and creating relief designs with freehand slip-trailing. Fashions in fine tablewares were changing. Some East Gaulish producers made bowls and cups decorated only with rouletted or stamped decoration, and in the 3rd and 4th centuries,

229:

signatures of mouldmakers, makes it possible to build up a very detailed knowledge of the industry. Careful observation of form and fabric is therefore usually enough for an archaeologist experienced in the study of sigillata to date and identify a broken

367:

quickly began to copy the shapes of plain Arretine dishes and cups in the wares now known as Gallo-Belgic, and in South and Central Gaul, it was not long before local potters also began to emulate the mould-made decoration and the glossy red slip itself.

98:

Modern "terra sig" should be clearly distinguished from the close reproductions of Roman wares made by some potters deliberately recreating and using the Roman methods. The finish called 'terra sigillata' by studio potters can be made from most

1169:) to impress the pattern on the bowl before the clay was hard. It is also possible that it was sometimes made by holding a blade-like tool against the vessel as it turned on the wheel, allowing the tool to judder against the surface of the clay.

429:. Research on Arretine ware has continued very actively throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, for example with the publication and revision of an inventory of the known potter's stamps ("Oxé-Comfort-Kenrick") and the development of a

621:

name-stamps incorporated into the decoration, clearly acting as brand-names or advertisements. Though these vessels were very competently made, they are heavy and somewhat coarse in form and finish compared with earlier Gaulish samian ware.

167:... is a Latin term used by modern scholars to designate a class of decorated red-gloss pottery .... not all red-gloss ware was decorated, and hence the more inclusive term 'Samian ware' is sometimes used to characterize all varieties of it.

442:

1559:

Many of the Central Gaulish types were first drawn and classified in Déchelette 1904. Oswald's classification (Oswald 1936–7) is much fuller, covering South, Central and East Gaulish types, but is marred by the poor quality of the

417:'s massive encyclopedia included a chapter praising the refined Roman ware discovered in his native city, "what is perhaps the first account of an aspect of ancient art to be written since classical times". The chronicler

69:

Terra sigillata as an archaeological term refers chiefly to a specific type of plain and decorated tableware made in Italy and in Gaul (France and the Rhineland) during the Roman Empire. These vessels have glossy surface

192:(1895), is still in use (as e.g. "Dr.29"), and there have been many others, such as the classifications of Déchelette, Knorr, Hermet, Walters, Curle, Loeschcke, Ritterling, Hermet and Ludowici, and more recently, the

196:

of Arretine forms and Hayes's type-series of African Red Slip and Eastern sigillatas. These reference sometimes make it possible to date the manufacture of a broken decorated sherd to within 20 years or less.

624:

From the end of the 2nd century, the export of sigillata from Central Gaul rapidly, perhaps even abruptly, ceased. Pottery production continued, but in the 3rd century, it reverted to being a local industry.

786:

In the 1980s two primary groups of Eastern Terra Sigillata in the Eastern Mediterranean basin were distinguished as ETS-I and ETS-II based on their chemical fingerprints as shown by analysis by instrumental

200:

Most of the forms that were decorated with figures in low relief were thrown in pottery moulds, the inner surfaces of which had been decorated using fired-clay stamps or punches (usually referred to as

612:

Graufesenque and other South Gaulish centres. Figure-types and decorative details have been classified, and can often be linked to specific workshops Lezoux wares also included vases decorated with

537:

cups, especially Dr.18 (a shallow dish) and Dr.27 (a little cup with a distinctive double curve to the profile), many of which bear potters' name-stamps, and the large decorated forms 29, 30 and 37.

379:, too, tended to match the subjects and styles seen on silver plate, namely mythological and genre scenes, including erotic subjects, and small decorative details of swags, leafy wreaths and ovolo (

451:

1277:

Oswald & Pryce 1920 covers the main typologies of the early 20th century. Ettlinger 1990 is the current reference system for Arretine, and Hayes 1972 and 1980 for the late Roman material.

504:

South Gaulish samian typically has a redder slip and deeper pink fabric than Italian sigillata. The best slips, vivid red and of an almost mirror-like brilliance, were achieved during the

425:

being excavated in Germany. Dragendorff's classification was expanded by other scholars, including S. Loeschcke in his study of the Italian sigillata excavated at the early Roman site of

371:

The most recognisable decorated Arretine form is Dragendorff 11, a large, deep goblet on a high pedestal base, closely resembling some silver table vessels of the same period, such as the

1047:

temperature than normal bisque temperature of approximately 900 °C. Higher firing temperatures tend to remove the burnished effect because the clay particles start to recrystallize.

493:

in August AD 79, was a consignment of South Gaulish sigillata, still in its packing crate; like all finds from the Vesuvian sites, this hoard of pottery is invaluable as dating evidence.

91:. Closely related pottery fabrics made in the North African and Eastern provinces of the Roman Empire are not usually referred to as terra sigillata, but by more specific names, e.g.

677:, Blickweiler and other sites is of interest and importance mainly to specialists, two sources stand out because their wares are often found outside their own immediate areas, namely

815:

inland from the southern Turkish coast has been excavated since it was discovered in 1987, and its wares traced to many sites in the region. It was active from around 25 to 550 AD.

95:. All these types of pottery are significant for archaeologists: they can often be closely dated, and their distribution casts light on aspects of the ancient Roman economy.

2200:

Sciau, P., Relaix, S., Kihn, Y. & Roucau, C., "The role of Microstructure and Composition in the Brilliant Red Slip of Roman Terra Sigillata Pottery from Southern Gaul",

548:

developed its own distinctive forms and designs, and continued in production into the late Roman period, the 4th and 5th centuries AD. It was not exported to other regions.

1100:

In 1580, a miner named Adreas Berthold traveled around Germany selling Silesian terra sigillata made from a special clay dug from the hills outside the town of Striga, now

1316:

in the early 20th century included form-classifications which are still in use for forms that were absent from Dragendorff's original list: Loeschcke 1909; Ritterling 1913

413:

In the Middle Ages, examples of the ware that were serendipitously discovered in digging foundations in Arezzo drew admiring attention as early as the 13th century, when

58:

technique supposedly inspired by ancient pottery. Usually roughly translated as 'sealed earth', the meaning of 'terra sigillata' is 'clay bearing little images' (latin

2070:

Katalog V. Stempel-Namen und Bilder römischer Töpfer, Legions-Ziegel-Stempel, Formen von Sigillata und anderen Gefäßen aus meinen Ausgrabungen in Rheinzabern 1901-1914

402:, the Po valley and at other Italian cities. By the beginning of the 1st century AD, some of them had set up branch factories in Gaul, for example at La Muette near

322:

and early Roman period. That picture must itself be seen in relation to the luxury tablewares made of silver. Centuries before Italian terra sigillata was made,

318:

Arretine ware, in spite of its very distinctive appearance, was an integral part of the wider picture of fine ceramic tablewares in the Graeco-Roman world of the

62:), not 'clay with a sealed (impervious) surface'. The archaeological term is applied, however, to plain-surfaced pots as well as those decorated with figures in

1097:, it was seen as a proof against poisoning, as well as a general cure for any bodily impurities, and it was highly prized as a medicine and medicinal component.

1152:

in the 18th century. The parallel with 'china' is the reason why the late Professor Eric Birley favoured the use of a lower-case initial for 'samian'. (Birley

771:(or Cypriot sigillata) from Cyprus, as there is still much to be learnt about this material. While eastern sigillata C is known to come from Çandarli (ancient

1749:

46:

is a term with at least three distinct meanings: as a description of medieval medicinal earth; in archaeology, as a general term for some of the fine red

949:

1922:

Names on terra sigillata: an index of makers' stamps and signatures on Gallo-Roman terra sigillata (samian ware), Vol. 1 (A to AXO), Vol.2 (B to CEROTCUS

937:

925:

961:

889:

714:

in Britain, apparently initiated by potters from the East Gaulish factories at Sinzig, a centre that was itself an offshoot of the Trier workshops.

1779:

Rankin, Alisha; Rivest, Justin (July 14, 2016). "History of Clinical Trials: Medicine, Monopoly, and the Premodern State — Early Clinical Trials".

1132:

The meaning and etymology of 'samian ware' is a somewhat complex matter, fully addressed in King 1980. There is ancient authority for the use of

75:

existing traditions of pottery manufacture, and where the clay deposits proved suitable. The products of the Italian workshops are also known as

406:

in Central Gaul. Nor were the classic wares of the Augustan period the only forms of terra sigillata made in Italy: later industries in the

1191:

1248:

1144:, 'to polish' is probably connected. However, it would be unwise to exclude all possible historical associations with the island of

858:. From about the 4th century AD, competent copies of the fabric and forms were also made in several other regions, including

398:

Italian sigillata was not made only at or near Arezzo itself: some of the important Arezzo businesses had branch factories in

2157:

2091:

1937:

1929:

913:

527:

South Gaulish bowl, Dr.37, from the late 1st century AD, with a stamp of the potter Mercato in the decoration. British Museum

2374:

2364:

1008:

re-invented the method of making terra sigillata of Roman quality and obtained patent protection for this procedure at the

217:('sprigged') techniques were sometimes used to decorate vessels of closed forms.{{|Closed forms: shapes such as vases and

901:

434:

generation asks new questions and applies new techniques (such as analysis of clays) in the attempt to find the answers.

383:) borders that may be compared with elements of Augustan architectural ornament. The deep form of the Dr.11 allowed the

2252:

2227:

2195:

2142:

2127:

2042:

2014:

1965:

1857:

1829:

1712:, Sulzbach-Rosenberg 1984; Patents in the UK, France and the US are reported in the source, yet without patent-number

225:, combined in some cases with name-stamps of workshops incorporated into the decoration, and also sometimes with the

1757:

1043:

smallest clay particles, produces terra sigillata. The remaining larger clay-particle bottom layers are discarded.

1165:'Rouletted' decoration: this is a regular, notched surface texture, created by using a tool with a toothed wheel (

2267:

1010:

1192:"Gérard Morla, céramiste, réalise des copies de poteries sigillées moulées, pour les musées et les particuliers"

469:

Sigillata vessels, both plain and decorated, were manufactured at several centres in southern France, including

2359:

1690:

Hayes 1972 and Hayes 1980 are the standard reference works: Hayes 1997, pp. 59–64 provides a succinct summary.

1675:

1817:

1632:

The summary in Hayes 1997, pages 52–59 illustrates the main forms and describes the characteristics of wares.

811:. However this classification has been criticized, and is not universally accepted. A potter's quarter at

66:, because it does not refer to the decoration but to the makers stamp impressed in the bottom of the vessel.

1679:

2291:

617:

matching cup and dish with a curved horizontal rim embellished with a stylised scroll of leaves in relief.

1085:. The latter was called "sealed" because cakes of it were pressed together and stamped with the head of

788:

172:

made in ancient Gaul. In European languages other than English, terra sigillata, or a translation (e.g.

2281:

1722:

997:

firing. Terra sigillata is also used as a brushable decorative colourant medium in higher temperature

1656:

Archaeological and historical aspects of West-European societies: album amicorum André Van Doorselaer

662:

1035:

363:

taste and technical expertise. Pottery industries in the areas we now call north-east France and

1421:

The history of sigillata manufacture in Italy is succinctly summarised in Hayes 1997, pages 41–52.

54:

made in specific areas of the Roman Empire; and more recently, as a description of a contemporary

2369:

1199:

839:

271:

1667:

1643:

The Provenience, Typology and Chronology of Eastern Terra Sigillata of the Eastern Mediterranean

1038:

is often added to the watery clay/water slip mixture to facilitate separation of fine particle

748:

724:

298:

1055:

Since the 18th century Samian ware pots have been found in sufficient numbers in the sea near

1843:

La céramique gallo-romaine d'Argonne du IVe siècle et la terre sigillée décorée à la molette,

824:

92:

47:

2186:

Roberts, Paul, 'Mass-production of Roman Finewares', in Ian Freestone & David Gaimster,

878:

as well. There is a great variety of monogram crosses and plain crosses amongst the stamps.

986:

603:

565:

533:

323:

104:

496:

8:

1401:

989:

of raw clay surfaces to promote glossy surface effects in low fire techniques, including

768:

760:

752:

744:

723:

Arretine plain-ware shapes quite closely. There were evidently centres of production in

641:

There were numerous potteries manufacturing terra sigillata in East Gaul, which included

573:

414:

277:

Many of the Gaulish manufacturing sites have been extensively excavated and studied. At

262:

222:

1870:

Dragendorff, Hans, 'Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der griechischen und römischen Keramik',

1641:

Gunneweg, J., 1980 Ph.D.Thesis, Hebrew University; Gunneweg, Perlman and Yellin, 1983,

1614:

Tyers 1996, pp. 136–7. The stamps have been classified in Chenet 1941 and Hübener 1968

179:

2286:

2248:

2223:

2191:

2153:

2138:

2123:

2087:

2038:

2010:

1961:

1933:

1925:

1853:

1825:

1796:

1671:

1663:

1149:

990:

780:

706:

116:

1470:

Oxé & Comfort 1968; Oxé & Comfort & Kenrick 2000; Ettlinger et al. 1990.

1977:

Hübener, W., 'Eine Studie zur spätrömischen Rädchensigillata (Argonnensigillata)',

1917:

1788:

577:

569:

505:

418:

189:

149:

128:

without further qualification normally denotes the Arretine ware of Italy, made at

1654:

Poblome, Jernen, "The Ecology of Sagalassos (Southwest Turkey) Red Slip Ware", in

83:

and have been collected and admired since the Renaissance. The wares made in the

19:

1528:

Examples of these may be found in Hermet's own type-sequence, Hermet 1934, Pl.4—5

1060:

1031:

985:, 'terra sigillata' describes only a watery refined slip used to facilitate the

829:

772:

764:

654:

500:

South Gaulish plain forms, showing standardisation of size. Millau Museum, France

447:

278:

137:

71:

51:

2084:

Die italische Terra Sigillata mit Auflagenverzierung. Katalog der Applikenmotive

1313:

1222:

1113:

1090:

1078:

1072:

556:

540:

A local industry inspired by Arretine and South Gaulish imports grew up in the

462:

457:

380:

258:

55:

693:

bowls are of very poor quality, with crude decoration and careless finishing.

523:

237:

2353:

1547:

1221:

Roberts, Paul, "Mass-production of Roman Finewares", in Freestone, Ian &

998:

736:

589:

346:

1800:

1039:

1027:

943:

Profile drawing of form Dragendorff 11. 1st century BC–early 1st century AD

875:

865:

808:

564:

The principal Central Gaulish samian potteries were situated at Lezoux and

1497:

See Tyers 1996, p. 106, fig. 90 for a map of the Gaulish production sites

710:

relief-decorated samian ware included a brief and unsuccessful venture at

633:

2120:

A Catalogue of the Signatures, Shapes and Chronology of Italian Sigillata

1792:

1094:

982:

678:

394:

Mould for an Arretine Dr.11, manufactured in the workshop of P. Cornelius

376:

319:

157:

274:', the fusion of Classical and native cultural and artistic traditions.

214:

1325:

Webster 1996, pp. 9–12 provides a useful summary. For a report on the

1056:

859:

812:

711:

470:

372:

266:

120:

A decorated Arretine vase (Form Dragendorff 11) found at Neuss, Germany

2049:

Töpfer und Fabriken verzierter Terra-sigillata des ersten Jahrhunderts

1708:

Patent No. 206 395, Class 80b, Group 23; according to: Heinl, Rudolf;

1156:, 1960s, and see also Stanfield and Simpson 1958, p.xxxi, footnote 1).

1136:

to describe pottery with a polished surface in literary usage (Pliny,

87:

factories are often referred to by English-speaking archaeologists as

2343:

994:

796:

613:

597:

478:

407:

210:

36:

31:

2234:

Un four de la Graufesenque (Aveyron): la cuisson des vases sigillés

1101:

843:

804:

776:

732:

646:

490:

482:

334:

1309:

1086:

855:

851:

847:

756:

728:

670:

658:

486:

474:

426:

390:

364:

330:

226:

2179:

Ritterling, E., 'Das frührömische Lager bei Hofheim im Taunus',

1093:. This soil's particular mineral content was such that, in the

310:

2056:

Terra-Sigillata-Gefässe des ersten Jahrhunderts mit Töpfernamen

1911:

Terra Sigillata. Ein Weltreich im Spiegel seines Luxusgeschirrs

1082:

792:

740:

682:

674:

666:

642:

585:

541:

355:

254:

218:

206:

145:

141:

129:

80:

63:

2333:

Princeton, NJ: American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

1408:

In: Ettlinger et al. 1990, pp. 4–13; von Schnurbein, Siegmar:

1587:

For a good selection of examples, see Garbsch 1982, pp. 54–74

1145:

800:

686:

650:

306:(libation bowl) with mould-made relief decoration. c. 300 BC.

231:

153:

2317:

Pottery In the Roman World: An Ethnoarchaeological Approach.

1890:

Conspectus formarum terrae sigillatae italico modo confectae

1836:

Catalogue of Italian Terra-Sigillata in the Ashmolean Museum

775:), there were likely other workshops in the wider region of

2135:

Katalog der Punzenmotive in der arretinischen Reliefkeramik

1023:

977:

In contrast to the archaeological usage, in which the term

509:

403:

399:

246:

133:

100:

84:

967:

Profile drawing of form Dragendorff 30. 1st-2nd century AD

955:

Profile drawing of form Dragendorff 37. 1st–3rd century AD

2173:

Die Bilderschüsseln der römischen Töpfer von Rheinzabern

2165:

Die Bilderschüsseln der römischen Töpfer von Rheinzabern

637:

Rheinzabern barbotine-decorated vase, form Ludowici VMe

183:

Profile drawing of form Dragendorff 29. 1st century AD.

1754:

The University of Nottingham Department of Archaeology

1662:, 1996, Ed. Marc Lodewijckx, Leuven University Press,

1077:

The oldest use for the term terra sigillata was for a

1026:

particles to separate into layers by particle size. A

895:

South Gaulish cup, form Hofheim 8, with a marbled slip

869:

African Red Slip flagons and vases, 2nd-4th century AD

607:

Central Gaulish samian jar with 'cut-glass' decoration

132:, and Gaulish samian ware manufactured first in South

1605:

Ludowici 1927; Ricken 1942; Ricken & Fischer 1963

1506:

Atkinson, D., "A hoard of Samian ware from Pompeii",

838:

centres of production were in the Roman provinces of

2019:

King, Anthony, "A graffito from La Graufesenque and

981:

refers to a whole class of pottery, in contemporary

2122:, Bonn 1968, revised by Philip Kenrick, Bonn 2000,

931:

Gaulish Dr.36, with barbotine decoration on the rim

881:

461:South Gaulish Dragendorff 29, late 1st century AD.

354:Arretine ware began to be manufactured at and near

2181:Annalen des Vereins für Nassauische Altertumskunde

1904:Die Terra-Sigillata-Manufaktur von Sinzig am Rhein

584:. 27 BC–AD 14), but it was not until the reign of

576:. Production had already begun at Lezoux in the

1623:Tyers 1996. pp. 114–116; Hull 1963; Fischer 1969.

1259:As both King and Boardman do in their main texts.

2351:

1432:The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity

1017:

833:Late Roman African Red Slip dish, 4th century AD

16:Types of pottery; also, medieval medicinal earth

2188:Pottery in the Making: World Ceramic Traditions

2167:(Tafelband), Darmstadt 1942 (= Ludowici Kat.VI)

2113:An Introduction to the study of terra sigillata

1811:

1288:An Introduction to the Study of terra sigillata

1227:Pottery in the Making: World Ceramic Traditions

1022:Modern terra sigillata is made by allowing the

783:appears as a successor to Eastern sigillata C.

1865:Les vases céramiques ornés de la Gaule romaine

1406:Die italische Produktion: Die klassische Zeit.

1374:Hayes 1997, pp.40-41: Garbsch 1982, pp. 26-30

1212:King 1983, p.253 (definition) and pp. 183–186.

551:

350:An Arretine stamp used for impressing a mould

2171:*Ricken, H. & Fischer, Charlotte,(eds.)

1778:

1660:Acta archaeologica Lovaniensia: Monographiae

437:

2326:Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.

2324:Roman Pottery In the Archaeological Record.

2150:Werkstätten der arretinischen Reliefkeramik

2099:Index of Potters' Stamps on Terra Sigillata

2082:Ohlenroth, Ludwig & Schmid, Sebastian,

1710:Die Kunsttöpferfamilie Fischer aus Sulzbach

657:regions, but while the samian pottery from

628:

1715:

795:, whereas the ETS-II was probably made in

560:Central Gaulish Dr.30, stamped by Divixtus

111:

1897:Storia degli antichi vasi fittili aretini

1569:Stanfield & Simpson 1958, pp. 263–271

1479:Porten Palange 2004; Porten Palange 2009.

1299:e.g. Knorr 1919; Knorr 1952; Hermet 1934.

1063:that local people used them for cooking.

1050:

919:Flanged bowl, Dr.38, with profile drawing

2331:Pottery of the Roman Period: Chronology.

2310:Handbook of Mediterranean Roman Pottery.

2106:Index of figure-types on Terra Sigillata

1546:The basic study remains Stanfield &

1308:The site reports on the German forts at

907:South Gaulish cup of form Dragendorff 27

864:

828:

818:

632:

602:

555:

522:

495:

456:

441:

389:

345:

309:

297:

236:

178:

115:

30:

18:

2346:- specialist site with much information

2077:The Techniques of Painted Attic Pottery

2033:King, Anthony in: Henig, Martin (ed.),

2000:The Roman potters' kilns of Colchester,

1958:Handbook of Mediterranean Roman Pottery

1750:"Workshop Three: Research Partnerships"

993:and unglazed alternative western-style

410:and elsewhere continued the tradition.

2352:

2175:(Text), Bonn 1963 (= Ludowici Kat.VI)

1741:

727:; in western Turkey, exported through

2312:Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

2207:Stanfield, J., & Simpson, Grace,

1993:Trierer Reliefsigillata: Werkstatt II

1877:Dragendorff, H. & Watzinger, C.,

1596:Huld-Zetsche 1972; Huld-Zetsche 1993

1434:(Oxford: Blackwell) 1973:13 and note.

1412:In: Ettlinger et al. 1990, pp. 17–24.

791:(INAA). ETS-I originated in Eastern

717:

452:Gallo-Roman Museum, Tongeren, Belgium

329:Glossy-slipped black pottery made in

314:A black Megarian bowl, 2nd century BC

282:were so large, the excavation of the

2118:Oxé, August & Comfort, Howard,

1986:Trierer Reliefsigillata: Werkstatt I

1772:

743:, but archaeologists often refer to

152:, and at east Gaulish sites such as

1822:The Oxford History of Classical Art

1537:Johns 1977, p. 24: Tyers 1996, 113

13:

2261:

2111:Oswald, Felix & Pryce, T.D.,

1747:

1338:Sciau, P. et al 2005, pp.006.5.1-6

1066:

446:Terra sigillata bowl, produced in

205:) and some free-hand work using a

124:In archaeological usage, the term

14:

2386:

2344:Potsherd "Atlas of Roman pottery"

2337:

2148:Porten Palange, Francesca Paola,

2133:Porten Palange, Francesca Paola,

2009:, London 1971, revised edn. 1977

1645:, QEDEM 17, Jerusalem, Ahva Press

1286:Oswald, Felix & Pryce, T.D.,

1089:. Later, it bore the seal of the

972:

544:provinces in the 1st century AD.

450:, 50-85 A.D., found in Tongeren.

2329:Robinson, Henry Schroder. 1959.

2213:Les potiers de la Gaule Centrale

2211:, London 1958: revised edition,

2190:, London 1997, pp. 188–193

1951:Supplement to Late Roman Pottery

960:

948:

936:

924:

912:

900:

888:

882:Gallery of Roman terra sigillata

341:

2305:London: British School at Rome.

2245:Roman samian pottery in Britain

1702:

1693:

1684:

1648:

1635:

1626:

1617:

1608:

1599:

1590:

1581:

1572:

1563:

1553:

1540:

1531:

1522:

1513:

1500:

1491:

1482:

1473:

1464:

1455:

1446:

1437:

1424:

1415:

1395:

1386:

1377:

1368:

1359:

1350:

1341:

1332:

1319:

1302:

1293:

1280:

1247:King 1983, p.253. See also the

1159:

489:, destroyed by the eruption of

1410:Die außeritalische Produktion.

1271:

1262:

1253:

1241:

1232:

1215:

1206:

1183:

1126:

293:

253:The motifs and designs on the

1:

1018:Making modern terra sigillata

2292:Resources in other libraries

1981:168 (1968), pp. 241–298

1812:General and cited references

1488:Ohlenroth & Schmid 2024.

1176:

35:Terra sigillata beaker with

7:

2375:Types of pottery decoration

2365:History of ancient medicine

2063:Keramische Funde in Haltern

2030:11 (1980), pp. 139–143

2007:Arretine and samian pottery

1892:, Frankfurt and Bonn, 1990.

1229:, London, 1997, pp. 188–193

1198:(in French). Archived from

1107:

789:neutron activation analysis

552:Central Gaulish samian ware

27:bowl with relief decoration

10:

2391:

2204:, Vol.852, 006.5.1-6, 2005

1879:Arretinische Reliefkeramik

1070:

1004:In 1906 the German potter

822:

2322:Peña, J. Theodore. 2007.

2287:Resources in your library

2240:39 (1981), pp. 25–43

2101:, privately printed, 1931

1729:. Canterbury City Council

546:Terra sigillata hispanica

438:South Gaulish samian ware

421:also mentioned the ware.

2315:Peacock, D. P. S. 1982.

2220:Roman Pottery in Britain

1991:Huld-Zetsche, Ingeborg,

1984:Huld-Zetsche, Ingeborg,

1519:Johns 1977, p. 12, Pl.II

1508:Journal of Roman Studies

1119:

1036:sodium hexametaphosphate

739:, near Pergamon; and on

629:East Gaulish samian ware

148:and adjacent sites near

2209:Central Gaulish Potters

2152:, 2 vols., Mainz 2009,

2137:, 2 vols., Mainz 2004,

2035:A Handbook of Roman Art

1392:Oxé-Comfort 1968 / 2000

1140:35, 160), and the verb

665:, Chémery-Faulquemont,

112:Roman red gloss pottery

1884:Ettlinger, Elisabeth,

1383:Tyers 1996, pp.161–166

1365:Garbsch 1982, pp.30-33

1051:Reuse of Roman pottery

870:

834:

638:

608:

561:

528:

501:

466:

454:

395:

351:

315:

307:

250:

184:

169:

121:

93:African red slip wares

40:

28:

2360:Ancient Roman pottery

2308:Hayes, John W. 1997.

2301:Hayes, John W. 1972.

1916:Hartley, Brian &

1699:Hayes 1972, p. 19–20.

1443:Weiss 1973:13 note 4.

1356:Hayes 1997, pp. 37-40

1011:Kaiserliche Patentamt

868:

832:

825:African red slip ware

819:African red slip ware

636:

606:

559:

526:

499:

460:

445:

393:

349:

313:

301:

249:") at La Graufesenque

240:

182:

162:

119:

48:Ancient Roman pottery

34:

22:

2183:, 40, Wiesbaden 1913

1902:Fischer, Charlotte,

1863:Déchelette, Joseph,

1848:de la Bédoyère, G.,

1793:10.1056/NEJMp1605900

1402:Ettlinger, Elisabeth

1238:Boardman, pp. 276-77

1001:ceramic techniques.

854:and part of eastern

840:Africa Proconsularis

566:Les Martres-de-Veyre

50:with glossy surface

2303:Late Roman Pottery.

2202:Mater.Res.Soc.Proc.

2108:, Liverpool, 1937-7

1748:Rummel, Christoph.

1578:Johns 1977,pp.16–17

1510:4 (1914), pp. 26–64

1329:, see Vernhet 1981.

1081:from the island of

769:eastern sigillata D

761:eastern sigillata C

753:eastern sigillata B

745:eastern sigillata A

516:. AD 41–54; Nero,

512:periods (Claudius,

477:, La Graufesenque,

324:Attic painted vases

261:(ovolo) mouldings,

241:The remains of the

2086:, Wiesbaden 2024,

2075:Noble, Joseph V.,

2005:Johns, Catherine,

1944:Late Roman Pottery

1189:See, for example,

871:

850:; that is, modern

835:

718:Eastern sigillatas

639:

609:

580:period (Augustus,

562:

529:

502:

467:

455:

396:

352:

316:

308:

251:

185:

136:, particularly at

122:

41:

29:

2268:Library resources

2163:Ricken, H. (ed),

2158:978-3-88467-124-5

2092:978-3-7520-0615-5

2037:, Phaidon, 1983,

1979:Bonner Jahrbücher

1938:978-1-905670-17-8

1930:978-1-905670-16-1

1918:Dickinson, Brenda

1909:Garbsch, Jochen,

1906:, Düsseldorf 1969

1881:, Reutlingen 1948

1872:Bonner Jahrbücher

1678:, 9789061867227,

1268:Dragendorff 1895.

1150:Chinese porcelain

781:Phocaean red slip

532:relief-decorated

302:A Campanian ware

2382:

2319:London: Longman.

2243:Webster, Peter,

2222:, London 1996

2079:, New York, 1965

2058:, Stuttgart 1952

2051:, Stuttgart 1919

2025:

1956:Hayes, John W.,

1949:Hayes, John W.,

1942:Hayes, John W.,

1805:

1804:

1776:

1770:

1769:

1767:

1765:

1756:. Archived from

1745:

1739:

1738:

1736:

1734:

1727:Visit Canterbury

1719:

1713:

1706:

1700:

1697:

1691:

1688:

1682:

1652:

1646:

1639:

1633:

1630:

1624:

1621:

1615:

1612:

1606:

1603:

1597:

1594:

1588:

1585:

1579:

1576:

1570:

1567:

1561:

1557:

1551:

1544:

1538:

1535:

1529:

1526:

1520:

1517:

1511:

1504:

1498:

1495:

1489:

1486:

1480:

1477:

1471:

1468:

1462:

1459:

1453:

1450:

1444:

1441:

1435:

1430:Weiss, Roberto,

1428:

1422:

1419:

1413:

1399:

1393:

1390:

1384:

1381:

1375:

1372:

1366:

1363:

1357:

1354:

1348:

1345:

1339:

1336:

1330:

1323:

1317:

1306:

1300:

1297:

1291:

1284:

1278:

1275:

1269:

1266:

1260:

1257:

1251:

1245:

1239:

1236:

1230:

1219:

1213:

1210:

1204:

1203:

1202:on 21 July 2011.

1187:

1170:

1163:

1157:

1130:

964:

952:

940:

928:

916:

904:

892:

570:Clermont-Ferrand

419:Giovanni Villani

415:Restoro d'Arezzo

190:Hans Dragendorff

150:Clermont-Ferrand

23:Roman red gloss

2390:

2389:

2385:

2384:

2383:

2381:

2380:

2379:

2350:

2349:

2340:

2298:

2297:

2296:

2276:

2275:

2273:Terra sigillata

2271:

2264:

2262:Further reading

2258:

2215:, Gonfaron 1990

2176:

2104:Oswald, Felix,

2097:Oswald, Felix,

2072:. Jockgrim 1927

2061:Loeschcke, S.,

2047:Knorr, Robert,

2023:

1972:La Graufesenque

1814:

1809:

1808:

1777:

1773:

1763:

1761:

1760:on 8 March 2016

1746:

1742:

1732:

1730:

1723:"Roman pottery"

1721:

1720:

1716:

1707:

1703:

1698:

1694:

1689:

1685:

1653:

1649:

1640:

1636:

1631:

1627:

1622:

1618:

1613:

1609:

1604:

1600:

1595:

1591:

1586:

1582:

1577:

1573:

1568:

1564:

1558:

1554:

1545:

1541:

1536:

1532:

1527:

1523:

1518:

1514:

1505:

1501:

1496:

1492:

1487:

1483:

1478:

1474:

1469:

1465:

1460:

1456:

1451:

1447:

1442:

1438:

1429:

1425:

1420:

1416:

1400:

1396:

1391:

1387:

1382:

1378:

1373:

1369:

1364:

1360:

1355:

1351:

1346:

1342:

1337:

1333:

1324:

1320:

1307:

1303:

1298:

1294:

1285:

1281:

1276:

1272:

1267:

1263:

1258:

1254:

1246:

1242:

1237:

1233:

1223:Gaimster, David

1220:

1216:

1211:

1207:

1190:

1188:

1184:

1179:

1174:

1173:

1164:

1160:

1131:

1127:

1122:

1110:

1075:

1069:

1067:Medicinal earth

1053:

1032:sodium silicate

1020:

979:terra sigillata

975:

968:

965:

956:

953:

944:

941:

932:

929:

920:

917:

908:

905:

896:

893:

884:

827:

821:

759:in Asia Minor,

720:

631:

568:, not far from

554:

448:La Graufesenque

440:

344:

296:

279:La Graufesenque

165:Terra sigillata

144:, and later at

138:La Graufesenque

126:terra sigillata

114:

44:Terra sigillata

25:terra sigillata

17:

12:

11:

5:

2388:

2378:

2377:

2372:

2370:Medicinal clay

2367:

2362:

2348:

2347:

2339:

2338:External links

2336:

2335:

2334:

2327:

2320:

2313:

2306:

2295:

2294:

2289:

2284:

2278:

2277:

2266:

2265:

2263:

2260:

2256:

2255:

2241:

2230:

2216:

2205:

2198:

2184:

2170:

2169:

2168:

2161:

2146:

2131:

2116:

2109:

2102:

2095:

2080:

2073:

2068:Ludowici, W.,

2066:

2065:, Münster 1909

2059:

2052:

2045:

2031:

2017:

2003:

1996:

1989:

1982:

1975:

1968:

1954:

1947:

1940:

1914:

1913:, München 1982

1907:

1900:

1893:

1882:

1875:

1868:

1861:

1846:

1839:

1838:, Oxford 1968.

1832:

1818:Boardman, John

1813:

1810:

1807:

1806:

1787:(2): 106–109.

1771:

1740:

1714:

1701:

1692:

1683:

1647:

1634:

1625:

1616:

1607:

1598:

1589:

1580:

1571:

1562:

1552:

1539:

1530:

1521:

1512:

1499:

1490:

1481:

1472:

1463:

1461:Loeschcke 1909

1454:

1445:

1436:

1423:

1414:

1394:

1385:

1376:

1367:

1358:

1349:

1340:

1331:

1318:

1301:

1292:

1290:, London, 1920

1279:

1270:

1261:

1252:

1249:British Museum

1240:

1231:

1214:

1205:

1181:

1180:

1178:

1175:

1172:

1171:

1158:

1124:

1123:

1121:

1118:

1117:

1116:

1114:Cimolian earth

1109:

1106:

1091:Ottoman sultan

1079:medicinal clay

1073:Medicinal clay

1071:Main article:

1068:

1065:

1052:

1049:

1019:

1016:

974:

973:Modern pottery

971:

970:

969:

966:

959:

957:

954:

947:

945:

942:

935:

933:

930:

923:

921:

918:

911:

909:

906:

899:

897:

894:

887:

883:

880:

823:Main article:

820:

817:

747:from Northern

719:

716:

630:

627:

553:

550:

463:British Museum

439:

436:

381:egg-and-tongue

343:

340:

295:

292:

259:egg-and-tongue

174:terre sigillée

113:

110:

56:studio pottery

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

2387:

2376:

2373:

2371:

2368:

2366:

2363:

2361:

2358:

2357:

2355:

2345:

2342:

2341:

2332:

2328:

2325:

2321:

2318:

2314:

2311:

2307:

2304:

2300:

2299:

2293:

2290:

2288:

2285:

2283:

2280:

2279:

2274:

2269:

2259:

2254:

2253:1-872414-56-7

2250:

2247:, York 1996

2246:

2242:

2239:

2235:

2232:Vernhet, A.,

2231:

2229:

2228:0-7134-7412-2

2225:

2221:

2218:Tyers, Paul,

2217:

2214:

2210:

2206:

2203:

2199:

2197:

2196:0-7141-1782-X

2193:

2189:

2185:

2182:

2178:

2177:

2174:

2166:

2162:

2159:

2155:

2151:

2147:

2144:

2143:3-88467-088-3

2140:

2136:

2132:

2129:

2128:3-7749-3029-5

2125:

2121:

2117:

2115:, London 1920

2114:

2110:

2107:

2103:

2100:

2096:

2093:

2089:

2085:

2081:

2078:

2074:

2071:

2067:

2064:

2060:

2057:

2053:

2050:

2046:

2044:

2043:0-7148-2214-0

2040:

2036:

2032:

2029:

2022:

2018:

2016:

2015:0-7141-1361-1

2012:

2008:

2004:

2001:

1998:Hull, M. R.,

1997:

1994:

1990:

1987:

1983:

1980:

1976:

1973:

1969:

1967:

1966:0-7141-2216-5

1963:

1959:

1955:

1953:, London 1980

1952:

1948:

1946:, London 1972

1945:

1941:

1939:

1935:

1931:

1927:

1923:

1919:

1915:

1912:

1908:

1905:

1901:

1899:, Arezzo 1841

1898:

1895:Fabroni, A.,

1894:

1891:

1887:

1883:

1880:

1876:

1873:

1869:

1866:

1862:

1859:

1858:0-85263-930-9

1855:

1851:

1847:

1844:

1840:

1837:

1834:Brown, A. C.

1833:

1831:

1830:0-19-814386-9

1827:

1824:, 1993, OUP,

1823:

1819:

1816:

1815:

1802:

1798:

1794:

1790:

1786:

1782:

1775:

1759:

1755:

1751:

1744:

1728:

1724:

1718:

1711:

1705:

1696:

1687:

1681:

1677:

1673:

1669:

1665:

1661:

1658:, Issue 8 of

1657:

1651:

1644:

1638:

1629:

1620:

1611:

1602:

1593:

1584:

1575:

1566:

1556:

1549:

1543:

1534:

1525:

1516:

1509:

1503:

1494:

1485:

1476:

1467:

1458:

1449:

1440:

1433:

1427:

1418:

1411:

1407:

1403:

1398:

1389:

1380:

1371:

1362:

1353:

1344:

1335:

1328:

1322:

1315:

1311:

1305:

1296:

1289:

1283:

1274:

1265:

1256:

1250:

1244:

1235:

1228:

1224:

1218:

1209:

1201:

1197:

1193:

1186:

1182:

1168:

1162:

1155:

1151:

1147:

1143:

1139:

1135:

1129:

1125:

1115:

1112:

1111:

1105:

1103:

1098:

1096:

1092:

1088:

1084:

1080:

1074:

1064:

1062:

1058:

1048:

1044:

1041:

1037:

1033:

1029:

1025:

1015:

1013:

1012:

1007:

1002:

1000:

996:

992:

988:

984:

980:

963:

958:

951:

946:

939:

934:

927:

922:

915:

910:

903:

898:

891:

886:

885:

879:

877:

867:

863:

861:

857:

853:

849:

845:

841:

831:

826:

816:

814:

810:

806:

802:

798:

794:

790:

784:

782:

778:

774:

770:

766:

763:from ancient

762:

758:

754:

750:

746:

742:

738:

734:

730:

726:

715:

713:

708:

702:

700:

694:

690:

688:

684:

680:

676:

672:

668:

664:

660:

656:

652:

648:

644:

635:

626:

622:

618:

615:

605:

601:

599:

593:

591:

587:

583:

579:

575:

571:

567:

558:

549:

547:

543:

538:

535:

525:

521:

519:

515:

511:

507:

498:

494:

492:

488:

484:

480:

476:

472:

464:

459:

453:

449:

444:

435:

432:

428:

422:

420:

416:

411:

409:

405:

401:

392:

388:

386:

382:

378:

374:

369:

366:

361:

357:

348:

342:Arretine ware

339:

336:

332:

327:

325:

321:

312:

305:

300:

291:

287:

285:

280:

275:

273:

268:

264:

260:

256:

248:

244:

239:

235:

233:

228:

224:

220:

216:

212:

208:

204:

198:

195:

191:

181:

177:

175:

168:

166:

161:

159:

156:, Sinzig and

155:

151:

147:

143:

139:

135:

131:

127:

118:

109:

106:

102:

96:

94:

90:

86:

82:

78:

73:

67:

65:

61:

57:

53:

49:

45:

38:

33:

26:

21:

2330:

2323:

2316:

2309:

2302:

2282:Online books

2272:

2257:

2244:

2237:

2233:

2219:

2212:

2208:

2201:

2187:

2180:

2172:

2164:

2149:

2134:

2119:

2112:

2105:

2098:

2083:

2076:

2069:

2062:

2055:

2048:

2034:

2027:

2020:

2006:

1999:

1995:. Bonn 1993

1992:

1988:. Bonn 1972

1985:

1978:

1974:, Paris 1934

1971:

1970:Hermet, F.,

1957:

1950:

1943:

1921:

1910:

1903:

1896:

1889:

1885:

1878:

1871:

1867:, Paris 1904

1864:

1849:

1842:

1841:Chenet, G.,

1835:

1821:

1784:

1781:N Engl J Med

1780:

1774:

1762:. Retrieved

1758:the original

1753:

1743:

1731:. Retrieved

1726:

1717:

1709:

1704:

1695:

1686:

1680:google books

1659:

1655:

1650:

1642:

1637:

1628:

1619:

1610:

1601:

1592:

1583:

1574:

1565:

1555:

1542:

1533:

1524:

1515:

1507:

1502:

1493:

1484:

1475:

1466:

1457:

1452:Fabroni 1841

1448:

1439:

1431:

1426:

1417:

1409:

1405:

1397:

1388:

1379:

1370:

1361:

1352:

1343:

1334:

1326:

1321:

1304:

1295:

1287:

1282:

1273:

1264:

1255:

1243:

1234:

1226:

1217:

1208:

1200:the original

1196:Gérard Morla

1195:

1185:

1166:

1161:

1153:

1141:

1137:

1133:

1128:

1099:

1076:

1054:

1045:

1028:deflocculant

1021:

1009:

1006:Karl Fischer

1005:

1003:

978:

976:

876:Christianity

872:

836:

785:

721:

703:

698:

695:

691:

663:La Madeleine

640:

623:

619:

610:

594:

581:

563:

545:

539:

530:

517:

513:

503:

468:

430:

423:

412:

397:

384:

370:

359:

353:

328:

317:

303:

288:

283:

276:

272:romanisation

252:

242:

202:

199:

193:

186:

173:

170:

164:

163:

125:

123:

97:

88:

77:Aretine ware

76:

68:

59:

43:

42:

24:

2054:Knorr, R.,

2002:Oxford 1963

1850:Samian Ware

1764:15 December

1733:15 December

1550:1958 / 1990

1095:Renaissance

1014:in Berlin.

983:ceramic art

679:Rheinzabern

377:iconography

320:Hellenistic

294:Forerunners

158:Rheinzabern

89:samian ware

2354:Categories

2021:samia vasa

1845:Mâcon 1941

1676:9061867223

1347:Noble 1965

1327:grand four

1138:Nat. Hist.

1134:samia vasa

1057:Whitstable

987:burnishing

860:Asia Minor

813:Sagalassos

712:Colchester

649:, and the

508:and early

431:Conspectus

373:Warren Cup

284:grand four

243:grand four

194:Conspectus

105:burnishing

39:decoration

2028:Britannia

1874:96 (1895)

1668:0776-2984

1560:drawings.

1225:, (eds.)

1177:Citations

1154:pers.comm

1061:Herne Bay

991:primitive

797:Pamphylia

614:barbotine

479:Le Rozier

408:Po Valley

265:and vine

211:Barbotine

37:barbotine

1960:, 1997,

1852:, 1988,

1801:27410921

1167:roulette

1108:See also

1102:Strzegom

1030:such as

844:Byzacena

805:Aspendos

777:Pergamon

737:Çandarlı

733:Pergamon

701:(dish).

647:Saarland

598:Mortaria

578:Augustan

574:Auvergne

510:Neronian

506:Claudian

491:Vesuvius

483:Banassac

465:, London

385:poinçons

335:Campania

263:acanthus

215:appliqué

203:poinçons

1548:Simpson

1314:Hofheim

1310:Haltern

1142:samiare

1087:Artemis

856:Algeria

852:Tunisia

848:Numidia

757:Tralles

729:Ephesos

707:Argonne

681:, near

671:Remagen

659:Luxeuil

590:Britain

572:in the

542:Iberian

534:beakers

487:Pompeii

475:Montans

427:Haltern

375:. The

365:Belgium

331:Etruria

267:scrolls

227:cursive

219:flagons

140:, near

85:Gaulish

60:sigilla

2270:about

2251:

2238:Gallia

2226:

2194:

2156:

2141:

2126:

2090:

2041:

2013:

1964:

1936:

1928:

1886:et al.

1856:

1828:

1799:

1674:

1666:

1083:Lemnos

999:glazed

793:Cyprus

773:Pitane

767:, and

765:Pitane

741:Cyprus

699:Teller

685:, and

683:Speyer

675:Sinzig

667:Lavoye

645:, the

643:Alsace

586:Trajan

356:Arezzo

304:phiale

255:relief

245:("big

223:motifs

207:stylus

146:Lezoux

142:Millau

130:Arezzo

81:Arezzo

64:relief

1924:2008

1820:ed.,

1146:Samos

1120:Notes

1040:flocs

801:Perge

799:, at

755:from

749:Syria

725:Syria

687:Trier

655:Mosel

651:Rhine

232:sherd

154:Trier

101:clays

79:from

72:slips

52:slips

2249:ISBN

2224:ISBN

2192:ISBN

2154:ISBN

2139:ISBN

2124:ISBN

2088:ISBN

2039:ISBN

2011:ISBN

1962:ISBN

1934:ISBN

1932:and

1926:ISBN

1854:ISBN

1826:ISBN

1797:PMID

1766:2015

1735:2015

1672:ISBN

1664:ISSN

1312:and

1059:and

1024:clay

995:Raku

846:and

809:Side

807:and

653:and

481:and

471:Bram

404:Lyon

400:Pisa

360:reg.

333:and

247:kiln

213:and

134:Gaul

1789:doi

1785:375

1034:or

582:reg

518:reg

514:reg

2356::

2236:,

2026:|

1920:,

1888:,

1795:.

1783:.

1752:.

1725:.

1670:,

1404::

1194:.

842:,

803:,

751:,

735:;

731:;

689:.

673:,

669:,

661:,

473:,

2160:.

2145:.

2130:.

2094:.

2024:"

1860:.

1803:.

1791::

1768:.

1737:.

270:'

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.