719:. They had sought to prove that there were universal truths, entitled to be called laws of nature, from the concurrence of the testimonies of many men, peoples and ages, and through generalizing the operations of certain active principles. Cumberland admits this method to be valid, but he prefers the other, that from causes to effects, as showing more convincingly that the laws of nature carry with them a divine obligation. It shows not only that these laws are universal, but that they were intended as such; that man has been constituted as he is in order that they might be. In the prosecution of this method he expressly declines to have recourse to what he calls "the short and easy expedient of the

542:

770:

race would be an anomaly in the world had it not for end its conservation in its best estate; that benevolence of all to all is what in a rational view of the creation is alone accordant with its general plan; that various peculiarities of man's body indicate that he has been made to co-operate with his fellow men and to maintain society; and that certain faculties of his mind show the common good to be more essentially connected with his perfection than any pursuit of private advantage. The whole course of his reasoning proceeds on, and is pervaded by, the principle of final causes.

167:

554:"he was with difficulty persuaded to accept the offer, when it came to him from authority. The persuasion of his friends, particularly Sir Orlando Bridgeman, at length overcame his repugnance; and to that see, though very moderately endowed, he for ever after devoted himself, and resisted every offer of translation, though repeatedly made and earnestly recommended. To such of his friends as pressed an exchange upon him he was accustomed to reply, that Peterborough was his first espoused, and should be his only one."

250:

1074:

734:, the principal impugners of the existence of laws of nature. He cannot assume, he says, that such ideas existed from eternity in the divine mind, but must start from the data of sense and experience, and thence by search into the nature of things to discover their laws. It is only through nature that we can rise to nature's God. His attributes are not to be known by direct intuition. He, therefore, held that the ground taken up by the

65:

24:

615:. Its main design is to combat the principles which Hobbes had promulgated as to the constitution of man, the nature of morality, and the origin of society, and to prove that self-advantage is not the chief end of man, that force is not the source of personal obligation to moral conduct nor the foundation of social rights, and that the

782:. His utilitarianism is distinct from the individualism of some later utilitarians; it goes to the contrary extreme, by almost absorbing individual in universal good. To the question, "What is the foundation of rectitude?," he replies, the greatest good of the universe of rational beings. This is a version of utilitarianism.

704:

ultimate fact although it may be the statement of such a fact. And in what sense is a law of nature an "immutably true" proposition? Is it so because men always and everywhere accept and act on it, or merely because they always and everywhere ought to accept and act on it? The definition, in fact, explains nothing.

769:

His method was the deduction of the propriety of certain actions from the consideration of the character and position of rational agents in the universe. He argues that all that we see in nature is framed so as to avoid and reject what is dangerous to the integrity of its constitution; that the human

741:

His sympathies, however, were all on their side, and he would do nothing to diminish their chances of success. He would not even oppose the doctrine of innate ideas, because it looked with a friendly eye upon piety and morality. He granted that it might, perhaps, be the case that ideas were both born

691:

This definition, he says, will be admitted by all parties. Some deny that such laws exist, but they will grant that this is what ought to be understood by them. There is thus common ground for the two opposing schools of moralists to join issue. The question between them is, Do such laws exist or do

785:

Nor does it look merely to the lower pleasures, the pleasures of sense, for the constituents of good, but rises above them to include especially what tends to perfect, strengthen and expand our true nature. Existence and the extension of our powers of body and mind are held to be good for their own

549:

One day in 1691 he went, according to his custom on a post-day, to read the newspaper at a coffee-house in

Stamford, and there, to his surprise, he read that the king had nominated him to the bishopric of Peterborough. The bishop elect was scarcely known at court, and he had resorted to none of the

466:

restatement of the doctrine of the law of nature as furnishing the ground of the obligation of all the moral virtues. The work is heavy in style, and its philosophical analysis lacks thoroughness; but its insistence on the social nature of man, and its doctrine of the common good as the supreme law

793:

and some other writers have reproduced them as necessary to its defence against charges not less serious than even inconsistency. The answer which

Cumberland gives to the question, "Whence comes our obligation to observe the laws of nature?," is that happiness flows from obedience, and misery from

699:

as means to happiness seemed to him to be such laws. They precede civil constitution, which merely perfects the obligation to practise them. He expressly denied, however, that "they carry with them an obligation to outward acts of obedience, even apart from civil laws and from any consideration of

761:

of Hobbes. Cumberland maintained that the whole-hearted pursuit of the good of all contributes to the good of each and brings personal happiness; that the opposite process involves misery to individuals including the self. Cumberland never appealed to the evidence of history, although he believed

803:

reason he means merely the power of rising to general laws of nature from particular facts of experience. It is no peculiar faculty or distinctive function of mind; it involves no original element of cognition; it begins with sense and experience; it is gradually generated and wholly derivative.

802:

Reward and punishment, supplemented by future retribution, are, in his view, the sanctions of the laws of nature, the sources of our obligation to obey them. To the other great ethical question, How are moral distinctions apprehended?, he replies that it is by means of right reason. But by right

643:

is a book about how individuals can discover the precepts of natural law and the divine obligation which lies behind it. Could, or should, natural philosophy claim to be able to reveal substantial information about the nature of God's will, and also divine obligation? For writers who accepted a

577:, 1716) he presented a copy to the bishop, who began to study the language at the age of eighty-three. "At this age," says his chaplain, "he mastered the language, and went through great part of this version, and would often give me excellent hints and remarks, as he proceeded in reading of it."

703:

Many besides Hobbes must have felt dissatisfied with the definition. It is ambiguous and obscure. In what sense is a law of nature a "proposition"? Is it as the expression of a constant relation among facts, or is it as the expression of a divine commandment? A proposition is never in itself an

851:

Sanchoniatho's

Phoenician History: Translated from the First Book of Eusebius De Praeparatione Evangelica. With a Continuation of Sanchoniatho's History by Eratosthenes Cyrenaeus's Canon, which Dicaearchus connects with the First Olympiad. These Authors are illustrated with many Historical and

685:

immutably true propositions regulative of voluntary actions as to the choice of good and the avoidance of evil, and which carry with them an obligation to outward acts of obedience, even apart from civil laws and from any considerations of compacts constituting

841:

An Essay towards the

Recovery of the Jewish Measures and Weights, comprehending their Monies; by help of ancient standards, compared with ours of England: useful also to state many of those of the Greeks and Romans, and the Eastern

831:

De legibus naturae disquisitio philosophica, in qua earum forma, summa capita, ordo, promulgatio, et obligatio e rerum natura investigantur; quin etiam elementa philosophiae

Hobbianae, cum moralis tum civilis, considerantur et

1006:

602:

Bishop

Cumberland was distinguished by his gentleness and humility. He could not be roused to anger, and spent his days in unbroken serenity. His favourite motto was that a man had better "wear out than rust out."

662:

follows Hobbes in attempting to provide a fully naturalistic account of the normative force of obligation and of the idea of a rational dictate, although he rejects Hobbes's theory that these derive entirely from

400:. In 1661 he was appointed one of the twelve preachers of the university. The Lord Keeper, who obtained his office in 1667, invited him to London, and in 1670 secured for him the rectory of

1045:

1089:

408:. In this year Cumberland married Anne Quinsey. He acquired credit by the fidelity with which he discharged his duties. In addition to his ordinary work he undertook the weekly lecture.

707:

The existence of such laws may, according to

Cumberland, be established in two ways. The inquirer may start either from effects or from causes. The former method had been taken by

580:

He died on 8 October 1718, in the eighty-seventh year of his age; he was found sitting in his library, in the attitude of one asleep, and with a book in his hand. He was buried in

623:. He endeavours, as a rule, to establish directly antagonistic propositions. He refrains, however, from denunciation, and is a fair opponent up to the measure of his insight.

730:

He thinks it ill-advised to build the doctrines of natural religion and morality on a hypothesis which many philosophers had rejected, and which could not be proved against

852:

Chronological

Remarks, proving them to contain a Series of Phoenician and Egyptian Chronology, from the first Man to the first Olympiad, agreeable to the Scripture Accounts

1215:

751:

422:. It is dedicated to Sir Orlando Bridgeman, and is prefaced by an "Alloquium ad Lectorem," contributed by Hezekiah Burton. It appeared during the same year as

357:

For some time he studied medicine; and although he did not adhere to this profession, he retained his knowledge of anatomy and medicine. He took the degree of

522:

1046:

http://estc.bl.uk/F/RYKIRRRM4ICBTTAB6H3K36BMSM98BEBXIBFI4NL45AME5NKPNU-40442?func=full-set-set&set_number=004944&set_entry=000008&format=999

521:

The preface contains an account by Payne of the life, character and writings of the author, published also in a separate form. A German translation by

514:. According to Parkin, Cumberland's work was in an anti-Catholic vein, accounting for its posthumous appearance. His domestic chaplain and son-in-law,

374:

82:

37:

1210:

1230:

1225:

1185:

1110:

934:

515:

196:

789:

Cumberland's views on this point were long abandoned by utilitarians as destroying the homogeneity and self-consistency of their theory; but

129:

101:

754:, the source of moral good. "No action can be morally good which does not in its own nature contribute somewhat to the happiness of men."

1094:

1205:

108:

695:

Hobbes did not deny that there were laws of nature, laws antecedent to government, laws even in a sense eternal and immutable. The

762:

that the law of universal benevolence had been accepted by all nations and generations; and he abstains from arguments founded on

1220:

115:

1180:

692:

they not? In reasoning thus

Cumberland obviously forgot what the position maintained by his principal antagonist really was.

43:

1056:

652:

understanding of the relationship between God and man (both

Cumberland and Hobbes), this was not an easy question to answer.

895:

A Brief Disquisition of the Laws of Nature according to the Principles laid down in the Rev. Dr Cumberland's Latin Treatise

347:

97:

862:

Origines gentium antiquissimae: Attempts for discovering the Times of the First Planting of Nations: in several Tracts

236:

218:

148:

51:

189:

1195:

401:

254:

1190:

794:

disobedience to them, not as the mere results of a blind necessity, but as the expressions of the divine will.

596:

561:

His charges to the clergy are described as plain and unambitious, the earnest breathings of a pious mind. When

86:

385:

378:

122:

1200:

619:

is not a state of war. The views of Hobbes seem to Cumberland utterly subversive of religion, morality and

339:

331:

311:

541:

807:

562:

550:

usual methods of advancing his temporal interest. "Being then sixty years old," says his great-grandson,

450:

558:

He discharged his new duties with energy and kept up his episcopal visitations till his eightieth year.

584:

the following day. The grave lies at the east end in a group of floor stones dedicated to the bishops.

766:, feeling that it was indispensable to establish the principles of moral right on nature as a basis.

645:

496:

179:

1062:

Bartleby - Cambridge History of English and American Literature - Hobbes and Contemporary Philosophy

467:

of morality, anticipate the direction taken by much of the ethical thought of the following century.

664:

183:

175:

318:, a group of ecclesiastical philosophers centred on Cambridge University in the mid 17th century.

430:, and was highly commended in a subsequent publication by Pufendorf. Stephen Darwall writes that

75:

1067:

Bartleby - Cambridge History of English and American Literature - Platonists and Latitudinarians

1142:

581:

480:

405:

276:

258:

200:

977:

Science, Religion and Politics in Restoration England: Richard Cumberland's De Legibus Naturae

1135:

1175:

1170:

735:

511:

455:

423:

358:

351:

315:

8:

877:

849:

588:

362:

996:

Stephen, Leslie. Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. 13. Macmillan: New York. 1888.

474:

The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21)

1126:

946:

860:

720:

811:

806:

This doctrine lies only in germ in Cumberland, but will be found in full flower in

790:

397:

343:

631:

829:

712:

616:

592:

570:

389:

366:

307:

883:

815:

779:

758:

370:

303:

292:

288:

269:

1164:

1152:

1085:

1080:

620:

566:

507:

296:

1098:. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 620–622.

502:

About this period he was apprehensive about the rise of Catholic influence.

890:

731:

708:

677:

529:(Magdeburg, 1755). The sequel to the work was likewise published by Payne:

446:

393:

335:

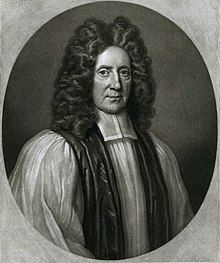

1023:

The full titles of Cumberland's works are long, and are given at the end.

757:

Cumberland's Benevolence is, deliberately, the precise antithesis to the

716:

436:

350:

in 1656, was incorporated the following year into the same degree in the

272:

1117:

1066:

1061:

435:

the Treatise was regarded as one of the three great works of the modern

763:

649:

418:

In 1672, at the age of forty, he published his earliest work, entitled

327:

882:(London, 1727), and John Towers (Dublin, 1750); French translation by

495:(1686). This work, dedicated to Pepys, obtained a copious notice from

249:

64:

724:

1079:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the

493:

An Essay towards the Recovery of the Jewish Measures and Weights

479:

English translations of the treatise were published in 1692, by

696:

627:

750:

Cumberland's ethical theory is summed up in his principle of

384:

Cumberland's first preferment, bestowed upon him in 1658 by

365:

in 1680. Among his contemporaries and intimate friends were

518:, edited it for publication soon after the bishop's death.

342:, where he obtained a fellowship. He took the degree of

742:

with us and afterwards impressed upon us from without.

545:

The grave of Richard Cumberland, Peterborough Cathedral

1118:

The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Cumberland

330:, where his father was a tailor. He was educated in

893:, published an abridgment of Cumberland's views in

527:

Cumberlands phonizische Historie des Sanchoniathons

89:. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

907:Account of the Life and Writings of R. Cumberland

279:from 1691. In 1672, he published his major work,

268:(15 July 1631 (or 1632) – 9 October 1718) was an

1162:

929:R. Cumberland als Begründer der englischen Ethik

373:, who was distinguished as a mathematician, and

188:but its sources remain unclear because it lacks

1034:The British Moralists and the Internal 'Ought'

970:The British Moralists and the Internal 'Ought'

672:

778:He may be regarded as the founder of English

657:Darwall (p. 106) writes that Cumberland

611:The philosophy of Cumberland is expounded in

1216:People educated at St Paul's School, London

575:Novum Testamentum Aegyptium, vulgo Copticum

52:Learn how and when to remove these messages

827:

326:He was born in the parish of St Ann, near

237:Learn how and when to remove this message

219:Learn how and when to remove this message

149:Learn how and when to remove this message

1084:

1005:

797:

738:could not be maintained against Hobbes.

540:

510:, was translated from the first book of

248:

1211:Fellows of Magdalene College, Cambridge

889:James Tyrrell (1642-1718), grandson of

1231:17th-century Church of England bishops

1226:18th-century Church of England bishops

1186:Alumni of Magdalene College, Cambridge

1163:

821:

606:

346:in 1653; and, having proceeded to the

944:

506:, on the author usually now known as

411:

98:"Richard Cumberland" philosopher

957:

941:, iv: 3 (1895), pp. 264 and 371

786:sakes without respect to enjoyment.

700:compacts constituting governments."

634:. According to Parkin (p. 141)

160:

87:adding citations to reliable sources

58:

17:

949:A History of English Utilitarianism

591:, who married Johanna (daughter of

13:

961:Richard Cumberland and Natural Law

499:, and was translated into French.

14:

1242:

1206:17th-century English philosophers

1104:

1090:Cumberland, Richard (philosopher)

773:

745:

597:Richard Cumberland, the dramatist

504:Sanchoniatho's Phoenician History

253:Richard Cumberland, engraving by

33:This article has multiple issues.

1072:

1057:Bartleby - Columbia - Cumberland

1007:"Cumberland, Richard (CMRT649R)"

879:A Treatise of the Laws of Nature

306:movement, along with his friend

165:

63:

22:

338:was a friend, and from 1649 at

302:Cumberland was a member of the

74:needs additional citations for

41:or discuss these issues on the

1221:People from the City of London

1039:

1026:

1017:

999:

990:

901:For biographical details see:

870:

595:), and his great-grandson was

531:Origines gentium antiquissimae

486:

1:

1181:17th-century writers in Latin

983:

945:Albee, Ernest (1902). "1/2".

909:(London, 1720); Cumberland's

536:

483:, and 1727, by John Maxwell.

461:. It has been described as a

379:Lord Keeper of the Great Seal

321:

828:Cumberland, Richard (1672).

525:appeared under the title of

340:Magdalene College, Cambridge

314:and closely allied with the

312:Magdalene College, Cambridge

7:

1011:A Cambridge Alumni Database

673:Laws of nature/natural laws

451:On the Law of War and Peace

10:

1247:

1013:. University of Cambridge.

876:John Maxwell (translator)

428:De jure naturae et gentium

1149:

1140:

1132:

1125:

964:. Cambridge, James Clark.

923:For his philosophy, see:

1127:Church of England titles

897:(London, 1692; ed. 1701)

665:instrumental rationality

174:This article includes a

1196:Bishops of Peterborough

1095:Encyclopædia Britannica

727:of the laws of nature.

203:more precise citations.

1143:Bishop of Peterborough

689:

680:are defined by him as

670:

655:

582:Peterborough Cathedral

556:

546:

491:Cumberland next wrote

470:

443:

277:Bishop of Peterborough

262:

1191:Anglican philosophers

798:Reward and punishment

752:universal benevolence

723:," the assumption of

682:

659:

636:

552:

544:

463:

432:

392:, was the rectory of

252:

958:Kirk, Linda (1987).

939:Philosophical Review

736:Cambridge Platonists

361:in 1663 and that of

352:University of Oxford

316:Cambridge Platonists

83:improve this article

1201:Doctors of Divinity

822:Works (full titles)

607:Philosophical views

523:Johan Philip Cassel

641:De legibus naturae

613:De legibus naturae

589:Denison Cumberland

547:

420:De legibus naturae

413:De legibus naturae

371:Sir Samuel Morland

281:De legibus naturae

266:Richard Cumberland

263:

176:list of references

1159:

1158:

1150:Succeeded by

1032:Stephen Darwall,

972:(1995), Chapter 4

968:Stephen Darwall,

927:F. E. Spaulding,

891:Archbishop Ussher

886:(Amsterdam, 1744)

626:The basis of his

587:His grandson was

445:the others being

375:Orlando Bridgeman

291:and opposing the

247:

246:

239:

229:

228:

221:

159:

158:

151:

133:

56:

1238:

1147:1691–1718

1133:Preceded by

1123:

1122:

1099:

1078:

1076:

1075:

1048:

1043:

1037:

1030:

1024:

1021:

1015:

1014:

1003:

997:

994:

965:

954:

866:

856:

845:

836:

791:John Stuart Mill

398:Northamptonshire

386:Sir John Norwich

332:St Paul's School

242:

235:

224:

217:

213:

210:

204:

199:this article by

190:inline citations

169:

168:

161:

154:

147:

143:

140:

134:

132:

91:

67:

59:

48:

26:

25:

18:

1246:

1245:

1241:

1240:

1239:

1237:

1236:

1235:

1161:

1160:

1155:

1146:

1138:

1107:

1102:

1088:, ed. (1911). "

1073:

1071:

1052:

1051:

1044:

1040:

1031:

1027:

1022:

1018:

1004:

1000:

995:

991:

986:

931:(Leipzig, 1894)

873:

865:. London. 1724.

859:

855:. London. 1720.

848:

844:. London. 1686.

839:

824:

816:associationists

800:

776:

748:

713:Robert Sharrock

675:

617:state of nature

609:

593:Richard Bentley

539:

489:

459:De jure naturae

416:

390:Rump Parliament

367:Hezekiah Burton

324:

308:Hezekiah Burton

287:), propounding

285:On natural laws

243:

232:

231:

230:

225:

214:

208:

205:

194:

180:related reading

170:

166:

155:

144:

138:

135:

92:

90:

80:

68:

27:

23:

12:

11:

5:

1244:

1234:

1233:

1228:

1223:

1218:

1213:

1208:

1203:

1198:

1193:

1188:

1183:

1178:

1173:

1157:

1156:

1151:

1148:

1139:

1134:

1130:

1129:

1121:

1120:

1115:

1106:

1105:External links

1103:

1101:

1100:

1086:Chisholm, Hugh

1069:

1064:

1059:

1053:

1050:

1049:

1038:

1025:

1016:

998:

988:

987:

985:

982:

981:

980:

973:

966:

955:

942:

932:

921:

920:

914:

913:(1807), i. 3-6

905:Squier Payne,

899:

898:

887:

884:Jean Barbeyrac

872:

869:

868:

867:

857:

846:

837:

823:

820:

799:

796:

780:utilitarianism

775:

774:Utilitarianism

772:

747:

746:Ethical theory

744:

678:Laws of nature

674:

671:

608:

605:

565:published the

538:

535:

488:

485:

415:

410:

323:

320:

304:Latitudinarian

289:utilitarianism

245:

244:

227:

226:

184:external links

173:

171:

164:

157:

156:

71:

69:

62:

57:

31:

30:

28:

21:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1243:

1232:

1229:

1227:

1224:

1222:

1219:

1217:

1214:

1212:

1209:

1207:

1204:

1202:

1199:

1197:

1194:

1192:

1189:

1187:

1184:

1182:

1179:

1177:

1174:

1172:

1169:

1168:

1166:

1154:

1153:White Kennett

1145:

1144:

1137:

1131:

1128:

1124:

1119:

1116:

1114:

1113:

1112:EpistemeLinks

1109:

1108:

1097:

1096:

1091:

1087:

1082:

1081:public domain

1070:

1068:

1065:

1063:

1060:

1058:

1055:

1054:

1047:

1042:

1036:(1995), p. 81

1035:

1029:

1020:

1012:

1008:

1002:

993:

989:

978:

974:

971:

967:

963:

960:

956:

952:

951:

948:

943:

940:

936:

933:

930:

926:

925:

924:

919:

915:

912:

908:

904:

903:

902:

896:

892:

888:

885:

881:

880:

875:

874:

864:

863:

858:

854:

853:

847:

843:

838:

834:

833:

826:

825:

819:

817:

813:

809:

804:

795:

792:

787:

783:

781:

771:

767:

765:

760:

755:

753:

743:

739:

737:

733:

728:

726:

722:

718:

714:

710:

705:

701:

698:

693:

688:

687:

681:

679:

669:

668:

666:

658:

654:

653:

651:

647:

640:

635:

633:

629:

624:

622:

621:civil society

618:

614:

604:

600:

598:

594:

590:

585:

583:

578:

576:

572:

568:

567:New Testament

564:

563:David Wilkins

559:

555:

551:

543:

534:

532:

528:

524:

519:

517:

513:

509:

508:Sanchuniathon

505:

500:

498:

494:

484:

482:

481:James Tyrrell

477:

475:

469:

468:

462:

460:

457:

453:

452:

448:

442:

440:

438:

431:

429:

425:

421:

414:

409:

407:

403:

399:

395:

391:

387:

382:

380:

377:, who became

376:

372:

368:

364:

360:

355:

353:

349:

345:

341:

337:

333:

329:

319:

317:

313:

309:

305:

300:

298:

297:Thomas Hobbes

294:

290:

286:

282:

278:

274:

271:

267:

260:

259:Thomas Murray

256:

251:

241:

238:

223:

220:

212:

202:

198:

192:

191:

185:

181:

177:

172:

163:

162:

153:

150:

142:

131:

128:

124:

121:

117:

114:

110:

107:

103:

100: –

99:

95:

94:Find sources:

88:

84:

78:

77:

72:This article

70:

66:

61:

60:

55:

53:

46:

45:

40:

39:

34:

29:

20:

19:

16:

1141:

1136:Thomas White

1111:

1093:

1041:

1033:

1028:

1019:

1010:

1001:

992:

976:

975:Jon Parkin,

969:

962:

959:

950:

947:

938:

935:Ernest Albee

928:

922:

917:

910:

906:

900:

894:

878:

861:

850:

840:

830:

805:

801:

788:

784:

777:

768:

756:

749:

740:

729:

725:innate ideas

709:Hugo Grotius

706:

702:

694:

690:

684:

683:

676:

661:

660:

656:

642:

638:

637:

625:

612:

610:

601:

586:

579:

574:

560:

557:

553:

548:

530:

526:

520:

516:Squier Payne

503:

501:

497:Jean Leclerc

492:

490:

478:

473:

471:

465:

464:

458:

449:

444:

434:

433:

427:

419:

417:

412:

394:Brampton Ash

383:

356:

336:Samuel Pepys

325:

301:

284:

280:

265:

264:

233:

215:

206:

195:Please help

187:

145:

136:

126:

119:

112:

105:

93:

81:Please help

76:verification

73:

49:

42:

36:

35:Please help

32:

15:

1176:1718 deaths

1171:1631 births

871:Authorities

717:John Selden

686:government.

646:voluntarist

632:benevolence

487:Other works

456:Pufendorf's

437:natural law

273:philosopher

201:introducing

1165:Categories

984:References

832:refutantur

814:and later

812:Mackintosh

764:revelation

732:Epicureans

721:Platonists

650:nominalist

630:theory is

537:Later life

402:All Saints

328:Aldersgate

322:Early life

295:ethics of

255:John Smith

109:newspapers

38:improve it

835:. London.

447:Grotius's

439:tradition

424:Pufendorf

44:talk page

916:Pepys's

533:(1724).

512:Eusebius

406:Stamford

334:, where

293:egoistic

209:May 2024

139:May 2024

1083::

911:Memoirs

842:Nations

808:Hartley

697:virtues

628:ethical

388:of the

270:English

197:improve

123:scholar

1077:

979:(1999)

759:egoism

571:Coptic

472:(From

454:, and

275:, and

257:after

125:

118:

111:

104:

96:

918:Diary

182:, or

130:JSTOR

116:books

715:and

648:and

639:The

102:news

1092:".

569:in

476:.)

426:'s

404:at

396:in

310:of

299:.

85:by

1167::

1009:.

937:,

818:.

810:,

711:,

599:.

381:.

369:,

363:DD

359:BD

354:.

348:MA

344:BA

186:,

178:,

47:.

953:.

667:.

573:(

441:,

283:(

261:.

240:)

234:(

222:)

216:(

211:)

207:(

193:.

152:)

146:(

141:)

137:(

127:·

120:·

113:·

106:·

79:.

54:)

50:(

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.