25:

850:

architecture also depict obsidian. Typically, the material's visual depiction in artwork is generally associated with autosacrifice and other types of sacrifice, including images of prismatic blades with bloody hearts on the blade's ends. Unfortunately, the majority of the material record is out of context yet the implications and interpretations that are drawn from artwork are substantial and reflect a corpus of beliefs and ideology involving obsidian.

603:(i.e., water absorbed into the material) observed indicates how long it has been since the obsidian surface was exposed (i.e., through flaking). Obsidian hydration dating is at times, however, unreliable. The rate of hydration can vary tremendously depending on annual rainfall and humidity levels, among other factors, and how these have varied since the piece was first produced (or how they vary if the piece moved from one ecological zone to another).

572:, and so on. While not as reliable as trace element analysis, and completely dependent on the experience of the researcher, visual sourcing has a number of advantages. Primarily, it is a cheap method that allows for the analysis of an entire obsidian assemblage. This is in comparison to trace element analysis which, due to high costs, allows for the analysis of only a small

932:, but these obsidian ear-spools have also been discovered in exclusively lower-status settings. Thus the value of obsidian can be considered highly variable. It was an important trade item, but is found in a variety of environments, unlike many items whose ownership was confined to the upper classes. Finally, there is no indication that obsidian was used as a

480:. Obsidian from Pachuca is notable because of its unique green-gold color and its internal purity which makes it one of the highest quality obsidian sources in Mesoamerica. It was much sought after and widely traded. Green obsidian is also found in the area of Tulancingo, but is distinct from Pachuca obsidian because of its internal

267:

139:

249:

was commonly used on larger-mass tools, such as bifaces, to prolong the tool's (and the raw material's) utility. While prismatic blades were generally not curated (in the traditional sense) due to their small size, utility of the tools may have been maintained by changing their function. In other

927:

culture obsidian was perhaps traded at a loss of human effort in transport across long distances. The profit from the trade lay in prestigious high-status items received in return. Obsidian has both been seen as a key element to

Teotihuacan's rise to power and as a side trade element that simply

649:

Obsidian was generally transported, where applicable, along coastal trade routes. Of primary importance is the circum-peninsular trade route that linked the southeast Maya area to the Gulf coast of Mexico. Examples of evidence of this include the higher quantities of obsidian found among coastal

487:

Substantial research has been carried out to decipher the

Guatemala region sources. As mentioned earlier, the Guatemalan region includes the El Chayal, Ixtepeque, and San Martin Jilotepeque sources, located in southern/southeastern Guatemala. Obsidian originating from Guatemala was widely used in

606:

Due to the nature of the geological formation of obsidian, and the impact that each unique formation incidence has on the appearance and geochemical properties of each source, the material serves as an excellent medium by which long-distance trade can be studied. In performing trace-element or

250:

words, as the edge of a blade lost its sharpness after long-term use, the blade may have been used in scraping activities, which does not require a very sharp edge, than as a cutting implement. Other curation techniques of prismatic blades involve reshaping them into other tool types, such as

849:

Most of the evidence that supports the many theories about obsidian use in

Mesoamerica comes from the artwork of the region. This artwork is seen in many forms including the aforementioned obsidian figurines, ear spools, beads, and vases. Stele and large carvings, sculpture, and murals on

235:

and 20 cm or slightly less in length, and they make it cylindrical and as thick as the calf of the leg, and they place the stone between the feet, and with a stick apply force to the edges of the stone, and at every push they give a little knife springs off with its edges like those of a

311:), has divided Mesoamerica into nine sub-regions with one or more obsidian sources in each. These subdivisions, while effective at systemizing the source characteristics and allowing for a more easily visualized distribution of sources, are still tentative. They are as follows:

630:(Andrews (1990: 13). It is unclear if trade for foreign obsidian contributed to the growth of Maya polities, or if it simply served as a mode for obtaining superior items or human labor. Generally, obsidian came into the Maya area via larger central places, such as Tikal,

294:

and their origins can be traced by their physical and geological properties. Before discussing these obsidian sources, a definition of what an obsidian source is must be established, as many of the terms used allow for different and competing interpretations.

298:

Sidrys et al. (1976) stated that an obsidian source area includes several outcroppings of obsidian, limited in spatial extent, which may or may not have common chemical features and may or may not have been used by ancient humans. Michael D. Glascock, of the

857:, a broad–faced club studded along its edges by obsidian prismatic blades. These weapons are predominantly used in ritual warfare and generally date to the Postclassic period. Earlier depictions of obsidian is usually restricted to their appearance as

563:

Visual sourcing is the process by which the source of obsidian artifacts are determined by the analysis of not only their visual appearance (e.g., color, inclusions, etc.) but also their physical attributes, such as surface texture, light

742:

Obsidian was also used in a variety of non-utilitarian contexts. Objects made of obsidian were used as associated grave goods, employed in sacrifice (in whatever form), and in art. Some non-utilitarian forms include miniature human

610:

It is clear that obsidian was a critical material in

Precolumbian Mesoamerican economies; it is ubiquitous throughout the region, and found in the material record of all cultures and time periods. The low bulk of obsidian in

622:. While the Maya had access to a number of local obsidian sources more readily available and (relatively) easily obtained, including El Chayal its main source, Pachuca obsidian remained an important trade good. The

916:

period progressed, obsidian became increasingly accessible to the lower classes of Maya civilization. Nevertheless, the Maya upper classes continued to remain in possession of the more prestigious

615:, which therefore required less effort in trade, and the large quantity of useful items that could be produced from a small amount of material, greatly contributed to obsidian's widespread use.

996:

When skillfully worked, the edges of prismatic blade made from obsidian can reach the molecular level (i.e., the material has a cutting edge that is only one molecule thick). Baigent (1999).

241:

As the distribution of obsidian sources in

Mesoamerica is generally limited, many areas and sites lacked a local obsidian source or direct access to one. As a result, tool curation through

82:

688:. Items made from this material had both utilitarian and ritual use. In many areas, it was available to all households regardless of socio-economic status, and was used in

618:

One example is the presence of

Pachuca obsidian from central Mexico, where Mexico City is now, and ostensibly under the control of Teotihuacan, in the Maya area during the

841:. Its ritualized use is not, however, restricted to high-status political and religious contexts, and it was clearly used within mundane domestic and household rituals.

492:, moving via a well-developed long-distance trade network that inter-connected much of the Maya area. Newer and tentative additions to the Guatemalan source area are

638:. Obsidian artifacts and tools were then redistributed to smaller and potentially dependent centers and communities. This is indicated by a lack of production

1170:

Glascock, Michael D.; Geoffrey E. Braswell; Robert H. Cobean (1998). "A Systematic

Approach to Obsidian Source Characterization". In M. Steven Shackley (ed.).

361:

114:. Obsidian was a highly integrated part of daily and ritual life, and its widespread and varied use may be a significant contributor to Mesoamerica's lack of

896:

Obsidian was widely distributed throughout

Mesoamerica by trade. Its importance to Mesoamerican societies has been compared to the value and importance of

696:, food preparation, and for many other daily activities. Morphologically, obsidian was worked into a variety of tool forms, including knives, lance and

448:

are the best known obsidian sources in

Guatemala and were commonly exploited in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. In fact, almost all Obsidian found in

300:

789:

spines. Its association with that act of bloodletting is important, as it is argued by some researchers that obsidian was seen as a type of

437:

1312:

1317:

357:

218:

Modern attempts to redesign production techniques are heavily based on

Spanish records and accounts of witnessed obsidian knapping.

130:

and inform scholars on economy, technological organization, long-distance trade, ritual organization, and socio-cultural structure.

411:

734:. The practical use of obsidian is obvious considering that the material can be used to make some of the sharpest edges on earth.

1102:

1352:

1307:

1103:"Compositional analysis of the Huitzila and La Lobera obsidian sources in the southern Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico"

512:

source, in the southwest of Guatemala, a source that was almost forgotten during the Classic and Post Classic periods.

1238:

1183:

1160:

853:

Some of the more significant portrayals of obsidian use involve blood-letting and warfare. One example includes the

68:

46:

39:

1229:(1989). "Coastal Maya Trade: Obsidian Densities at Wild Cane Cay". In Patricia A. McAnany; Barry L. Isaac (eds.).

908:, obsidian was a rare item in the lowland areas, found predominantly in high-status and ritual contexts. In many

157:

internal structure, obsidian is relatively easy to work, as it breaks in very predictable and controlled ways via

1332:

1023:

551:(XRF) are two analytical methods used to identify the types and amounts of trace elements. These data are then

500:. However, the El Chayal area is often seen as subsuming these two into one large source area. The Pre Classic

1060:

219:

1193:

Hester, Thomas R.; Robert N. Jack; Robert F. Heizer (1971). "The Obsidian of Tres Zapotes, Veracruz, Mexico".

1337:

200:

928:

augmented their already developing wealth. Obsidian forms part of many high-status items, such as valuable

1068:

Braswell, Geoffrey E.; Michael D. Glascock (1992). "A New Obsidian Source in the Highlands of Guatemala".

544:

308:

1347:

1260:

1077:

588:

445:

1279:(1991). "Obsidian Polyhedral Cores and Prismatic Blades in the Writing and Art of Ancient Mexico".

912:

excavations evidence of obsidian is likewise found most frequently in privileged settings. As the

539:

sources in Mesoamerica, as listed above. Each of these sources has a distinctive “fingerprint” of

33:

1251:(1996). "Ancient Maya Trading Ports and the Integration of Long-Distance and Regional Economies".

274:

Obsidian sources in Mesoamerica are limited in number and distribution, and are restricted to the

913:

905:

619:

473:

465:

371:

279:

304:

50:

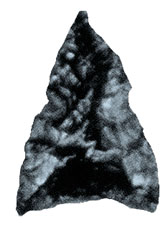

904:

provides varied evidence of the individual value placed on obsidian. For example, during the

291:

565:

429:

323:

231:

It is in this manner: First they get out a knife stone (obsidian core) which is black like

173:

122:

and contextual analysis of obsidian, including source studies, are important components of

543:

that proportionally vary due to the individual circumstances of each source's formation.

489:

161:. This contributed to its prolific use throughout Mesoamerica. It is obtained by either

8:

685:

573:

158:

1169:

865:, and it is commonly believed that the material was not associated with weapons such as

195:. The use of pecking, grinding, and carving techniques may also be employed to produce

1152:

1135:

548:

501:

343:

1357:

1234:

1231:

Research in Economic Anthropology: Prehistoric Maya Economics of Belize, Supplement 4

1179:

1156:

1089:

909:

834:

600:

509:

493:

453:

433:

242:

1139:

1342:

1288:

1264:

1248:

1226:

1125:

1117:

1081:

862:

782:

697:

678:

569:

481:

251:

208:

192:

166:

104:

86:

1175:

1057:

The Early Ceramic History of the Lowland Maya Vision and Revision in Maya Studies

1028:

1018:

818:

701:

596:

592:

347:

339:

204:

143:

119:

1207:

1192:

332:(includes the Cranzido and Partigo sources), in the central highlands of Mexico

223:

1292:

1268:

1085:

415:

266:

1326:

1093:

1047:

877:

866:

540:

270:

Map showing the locations of some of the main obsidian sources in Mesoamerica

255:

232:

108:

626:, from the Gulf coast likewise obtained its obsidian also from El Chayal in

822:

709:

643:

185:

1195:

Contributions of the University of California Archeology Research Facility

607:

visual analyses, the origins of an artifact's material can be determined.

419:

1318:

Obsidian Tools and Weapons of the Aztecs – World Museum of Man Collection

1313:

Obsidian Tools and Weapons of the Mayans – World Museum of Man Collection

1130:

924:

917:

901:

802:

693:

682:

477:

461:

401:

212:

188:

147:

123:

111:

1067:

1276:

1121:

854:

663:

577:

552:

385:

381:

246:

138:

115:

1214:. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI)

809:

is found in many of these tombs in addition to evidence of its use in

642:, including polyhedral cores, decortical flakes, and large percussion

1149:

Ancient Mexico & Central America: Archaeology and Culture History

756:

627:

612:

529:

441:

319:

287:

394:(a number of different quarries), in the central highlands of Mexico

1174:. Advances in Archaeological and Museum Science, Vol. 3. New York:

1100:

933:

929:

806:

786:

763:

744:

639:

635:

631:

525:

275:

196:

97:

93:

1208:"The Conference on Ancient Mesoamerican Obsidian Blade Production"

814:

731:

727:

714:

689:

536:

497:

469:

181:

127:

880:

system, a curved prismatic blade represents the phonetic value

810:

798:

760:

748:

723:

719:

705:

651:

283:

177:

162:

1212:

The Foundation Granting Department: Reports Submitted to FAMSI

897:

870:

858:

838:

826:

794:

790:

623:

532:

505:

449:

154:

100:

290:. These resources, however, are still quite abundant in the

81:

775:

771:

767:

752:

226:

observer, left this account of prismatic blade production:

555:

compared to data already available for the known sources.

830:

650:

sites, such as small island occupations off the coast of

785:(blood-letting) activities, serving as a substitute for

1044:

Ancient Traces: Mysteries in Ancient and Early History

404:, one source only), in the central highlands of Mexico

350:

sources), in the south-central Gulf lowlands of Mexico

1247:

1225:

1054:

844:

797:– its use in autosacrifice is therefore especially

1172:Archaeological Obsidian Studies: Method and Theory

460:Sources in the Valley of Mexico, which fell under

1205:

1146:

801:. Objects made of obsidian were often buried in

1324:

1110:Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry

1041:

428:– which incorporates all sources located in the

374:and Malpais), in the central highlands of Mexico

805:tombs as special deposits or caches. Obsidian

1101:Darling, J. Andrew; Frances Hayashida (1995).

301:University of Missouri Research Reactor Center

488:Mesoamerica and is found as far north as the

484:(e.g., it is a more milky or clouded green).

364:sources), in the central highlands of Mexico

1275:

1233:. Greenwich CT: JAI Press. pp. 17–56.

781:Obsidian was frequently used in ritualized

211:-like technique that removed blades from a

169:form from riverbeds or fractured outcrops.

1129:

520:

215:, was ubiquitous throughout Mesoamerica.

69:Learn how and when to remove this message

265:

137:

133:

80:

32:This article includes a list of general

1308:Obsidian use in Maya and Olmec Cultures

16:Aspect of Mesoamerican material culture

1325:

599:of an obsidian sample. The degree of

418:) – largest source in west Mexico (in

884:(Taube 1991) and results in the term

515:

388:), in the central highlands of Mexico

825:have been found in association with

456:sites originates from these sources.

207:production, a technique employing a

18:

873:until later phases in Mesoamerica.

583:

13:

900:to modern civilization. However,

829:offerings and related to specific

558:

103:that was an important part of the

38:it lacks sufficient corresponding

14:

1369:

1301:

1176:Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishing

845:Representation in art and writing

730:remains, indicating their use in

681:, has been found at nearly every

654:, then at sites located in-land.

591:is a method that allows for the

322:quarries), in the south-central

23:

1024:Mirrors in Mesoamerican culture

146:fragment from the Maya site of

1061:University of New Mexico Press

999:

990:

981:

972:

959:

946:

737:

668:

1:

1055:Andrews V, E. Wyllys (1990).

1034:

1005:For example, see Evans (2004)

203:, or other types of objects.

126:studies of past Mesoamerican

978:Braswell and Glascock (1992)

646:, among rural occupations.

7:

1012:

545:Neutron activation analysis

318:(includes the Zaragoza and

309:neutron activation analysis

10:

1374:

1261:Cambridge University Press

1206:Hirth, Kenneth G. (1999).

1147:Evans, Susan Toby (2004).

1078:Cambridge University Press

661:

261:

191:could be produced through

1353:Rock art in North America

1293:10.1017/S0956536100000377

1269:10.1017/S0956536100001280

1086:10.1017/s0956536100002285

1042:Baigent, Michael (1990).

987:See McKillop (1989; 1996)

712:. Blades have been found

589:Obsidian hydration dating

576:, preferably one that is

172:Following the removal of

939:

891:

53:more precise citations.

1333:Mesoamerican artifacts

657:

521:Trace element analysis

446:San Martín Jilotepeque

305:University of Missouri

280:Sierra Madre Mountains

271:

239:

150:

96:is a naturally formed

90:

793:originating from the

535:, comes from several

426:The Guatemalan region

292:archaeological record

269:

228:

159:conchoidal fracturing

141:

134:Production techniques

84:

1338:Mesoamerican society

1249:McKillop, Heather I.

1227:McKillop, Heather I.

430:Guatemalan highlands

282:as they run through

1281:Ancient Mesoamerica

1253:Ancient Mesoamerica

1153:Thames & Hudson

1070:Ancient Mesoamerica

774:, and as pieces of

686:archaeological site

464:control during the

326:lowlands of Mexico)

176:(when applicable),

165:source sites or in

1178:. pp. 15–65.

1122:10.1007/BF02038042

549:X-ray fluorescence

516:Analytical methods

502:Monte Alto culture

344:Guadalupe Victoria

272:

151:

91:

1348:Hardstone carving

906:Preclassic period

759:workings, carved

747:, ear spools and

698:projectile points

673:Obsidian, called

510:Tajumulco Volcano

490:Yucatán Peninsula

252:projectile points

243:edge-rejuvenation

222:, a 16th-century

79:

78:

71:

1365:

1296:

1272:

1244:

1222:

1220:

1219:

1202:

1189:

1166:

1143:

1133:

1107:

1097:

1064:

1063:. pp. 1–17.

1051:

1006:

1003:

997:

994:

988:

985:

979:

976:

970:

963:

957:

950:

936:in Mesoamerica.

920:green obsidian.

888:, as mentioned.

702:prismatic blades

679:Nahuatl language

584:Hydration dating

580:representative.

307:(which performs

209:pressure flaking

193:lithic reduction

184:, and expedient

105:material culture

87:projectile point

74:

67:

63:

60:

54:

49:this article by

40:inline citations

27:

26:

19:

1373:

1372:

1368:

1367:

1366:

1364:

1363:

1362:

1323:

1322:

1304:

1299:

1241:

1217:

1215:

1186:

1163:

1105:

1059:. Albuquerque:

1037:

1029:Prismatic blade

1019:Lithic analysis

1015:

1010:

1009:

1004:

1000:

995:

991:

986:

982:

977:

973:

964:

960:

951:

947:

942:

894:

847:

821:. For example,

740:

708:, and utilized

671:

666:

660:

597:relative dating

586:

561:

559:Visual sourcing

523:

518:

348:Las Derrumbadas

340:Pico de Orizaba

278:regions of the

264:

213:polyhedral core

205:Prismatic blade

144:prismatic blade

136:

75:

64:

58:

55:

45:Please help to

44:

28:

24:

17:

12:

11:

5:

1371:

1361:

1360:

1355:

1350:

1345:

1340:

1335:

1321:

1320:

1315:

1310:

1303:

1302:External links

1300:

1298:

1297:

1273:

1245:

1239:

1223:

1203:

1190:

1184:

1167:

1161:

1144:

1116:(2): 245–254.

1098:

1065:

1052:

1038:

1036:

1033:

1032:

1031:

1026:

1021:

1014:

1011:

1008:

1007:

998:

989:

980:

971:

958:

944:

943:

941:

938:

893:

890:

846:

843:

739:

736:

706:bifacial tools

670:

667:

659:

656:

585:

582:

560:

557:

541:trace elements

522:

519:

517:

514:

508:also used the

458:

457:

423:

405:

395:

389:

375:

365:

351:

338:(includes the

333:

327:

263:

260:

135:

132:

124:archaeological

77:

76:

31:

29:

22:

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1370:

1359:

1356:

1354:

1351:

1349:

1346:

1344:

1341:

1339:

1336:

1334:

1331:

1330:

1328:

1319:

1316:

1314:

1311:

1309:

1306:

1305:

1294:

1290:

1286:

1282:

1278:

1274:

1270:

1266:

1262:

1258:

1254:

1250:

1246:

1242:

1240:1-55938-051-9

1236:

1232:

1228:

1224:

1213:

1209:

1204:

1200:

1196:

1191:

1187:

1185:0-306-45804-7

1181:

1177:

1173:

1168:

1164:

1162:0-500-28440-7

1158:

1154:

1150:

1145:

1141:

1137:

1132:

1131:2027.42/43123

1127:

1123:

1119:

1115:

1111:

1104:

1099:

1095:

1091:

1087:

1083:

1079:

1075:

1071:

1066:

1062:

1058:

1053:

1049:

1045:

1040:

1039:

1030:

1027:

1025:

1022:

1020:

1017:

1016:

1002:

993:

984:

975:

968:

962:

955:

949:

945:

937:

935:

931:

926:

921:

919:

915:

911:

907:

903:

899:

889:

887:

883:

879:

878:Aztec writing

874:

872:

868:

864:

860:

856:

851:

842:

840:

836:

832:

828:

824:

820:

816:

813:dedications,

812:

808:

804:

800:

796:

792:

788:

784:

783:autosacrifice

779:

777:

773:

769:

765:

762:

758:

754:

750:

746:

735:

733:

729:

725:

721:

717:

716:

711:

707:

703:

699:

695:

691:

687:

684:

680:

676:

665:

655:

653:

647:

645:

641:

637:

633:

629:

625:

621:

620:Early Classic

616:

614:

608:

604:

602:

598:

594:

590:

581:

579:

578:statistically

575:

571:

567:

556:

554:

553:statistically

550:

546:

542:

538:

534:

531:

527:

513:

511:

507:

503:

499:

495:

491:

485:

483:

479:

475:

471:

467:

466:Early Classic

463:

455:

451:

447:

443:

439:

435:

431:

427:

424:

421:

417:

413:

409:

406:

403:

399:

396:

393:

390:

387:

383:

379:

376:

373:

369:

366:

363:

359:

355:

352:

349:

345:

341:

337:

334:

331:

328:

325:

321:

317:

314:

313:

312:

310:

306:

302:

296:

293:

289:

285:

281:

277:

268:

259:

257:

253:

248:

244:

238:

237:

234:

227:

225:

221:

216:

214:

210:

206:

202:

198:

194:

190:

187:

183:

179:

175:

170:

168:

164:

160:

156:

149:

145:

140:

131:

129:

125:

121:

117:

113:

110:

109:Pre-Columbian

106:

102:

99:

95:

88:

83:

73:

70:

62:

52:

48:

42:

41:

35:

30:

21:

20:

1284:

1280:

1256:

1252:

1230:

1216:. Retrieved

1211:

1198:

1194:

1171:

1148:

1113:

1109:

1073:

1069:

1056:

1043:

1001:

992:

983:

974:

966:

961:

953:

948:

922:

914:Late Classic

895:

885:

881:

875:

852:

848:

780:

741:

713:

683:Mesoamerican

674:

672:

648:

617:

609:

605:

587:

562:

524:

486:

459:

425:

407:

397:

391:

377:

367:

353:

335:

329:

315:

297:

273:

240:

230:

229:

217:

171:

152:

142:An obsidian

92:

65:

56:

37:

1277:Taube, Karl

925:Teotihuacan

918:Teotihuacan

902:archaeology

803:upper class

738:Ideological

694:agriculture

669:Utilitarian

568:, internal

478:Chicoloapan

462:Teotihuacan

416:Zinapécuaro

402:Zacualtipan

398:Zacualtipan

362:Santa Elena

199:, jewelry,

189:stone tools

153:Due to its

148:Chunchucmil

112:Mesoamerica

51:introducing

1327:Categories

1218:2007-03-30

1151:. London:

1046:. London:

1035:References

930:ear-spools

855:macuahuitl

815:potlaching

704:, general

664:Macuahuitl

662:See also:

566:reflection

547:(NAA) and

537:geological

386:Tepalcingo

382:Tulancingo

378:Tulancingo

247:sharpening

201:eccentrics

116:metallurgy

34:references

1287:: 61–70.

1263:: 49–62.

1201:: 65–131.

1094:0956-5361

1080:: 47–49.

965:Glascock

819:offerings

764:figurines

757:turquoise

628:Guatemala

613:transport

601:hydration

442:Ixtepeque

438:El Chayal

434:Tajumulco

420:Michoacán

320:Altotonga

288:Guatemala

245:and/or re

220:Motolinia

197:figurines

182:unifacial

163:quarrying

85:Obsidian

59:June 2017

1358:Obsidian

1140:97598146

1013:See also

934:currency

837:site of

807:debitage

799:symbolic

787:stingray

745:effigies

732:butchery

640:debitage

636:Palenque

632:Uaxactun

593:absolute

530:volcanic

526:Obsidian

504:and the

316:Zaragoza

276:volcanic

178:bifacial

128:cultures

98:volcanic

94:Obsidian

1343:Lithics

1048:Penguin

952:Hester

923:In the

876:In the

863:lancets

833:at the

749:labrets

728:mollusk

715:in situ

690:hunting

677:in the

570:opacity

498:Sansare

482:opacity

470:Pachuca

468:, were

392:Pachuca

358:Paredon

354:Paredon

336:Orizaba

303:at the

262:Sources

236:razor."

224:Spanish

47:improve

1237:

1182:

1159:

1138:

1092:

969:(1998)

967:et al.

956:(1971)

954:et al.

886:itztli

871:spears

859:razors

827:stelae

823:flakes

811:temple

761:animal

726:, and

724:rodent

720:rabbit

710:flakes

675:itztli

652:Belize

644:flakes

634:, and

574:sample

506:Olmecs

494:Jalapa

476:, and

474:Otumba

444:, and

412:Ucareo

408:Ucareo

372:Otumba

368:Otumba

346:, and

330:Bazoli

284:Mexico

174:cortex

167:nodule

155:glassy

120:Lithic

36:, but

1136:S2CID

1106:(PDF)

940:Notes

898:steel

892:Value

867:clubs

839:Tikal

817:, or

795:earth

791:blood

776:masks

772:vases

768:beads

751:with

718:with

624:Olmec

533:glass

450:Olmec

186:flake

101:glass

1235:ISBN

1180:ISBN

1157:ISBN

1090:ISSN

910:Maya

835:Maya

831:gods

755:and

753:gold

528:, a

496:and

454:Maya

452:and

414:and

384:and

360:and

324:Gulf

286:and

256:awls

254:and

1289:doi

1265:doi

1126:hdl

1118:doi

1114:196

1082:doi

882:itz

869:or

861:or

658:Use

595:or

233:jet

107:of

1329::

1283:.

1259:.

1255:.

1210:.

1199:13

1197:.

1155:.

1134:.

1124:.

1112:.

1108:.

1088:.

1076:.

1072:.

778:.

770:,

766:,

722:,

700:,

692:,

472:,

440:,

436:,

432:.

422:).

342:,

258:.

180:,

118:.

1295:.

1291::

1285:2

1271:.

1267::

1257:7

1243:.

1221:.

1188:.

1165:.

1142:.

1128::

1120::

1096:.

1084::

1074:3

1050:.

410:(

400:(

380:(

370:(

356:(

89:.

72:)

66:(

61:)

57:(

43:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.