1422:

him on his back, tying the hands to the sides and fastening the legs ... Soon comes the sacrificing priest—and this is no small office among them—armed with a stone knife, which cuts like steel, and is as big as one of our large knives. He plunges the knife into the breast, opens it, and tears out the heart hot and palpitating. And this as quickly as one might cross himself. At this point the chief priest of the temple takes it, and anoints the mouth of the principal idol with the blood; then filling his hand with it he flings it towards the sun, or towards some star, if it be night. Then he anoints the mouths of all the other idols of wood and stone, and sprinkles blood on the cornice of the chapel of the principal idol. Afterwards they burn the heart, preserving the ashes as a great relic, and likewise they burn the body of the sacrifice, but these ashes are kept apart from those of the heart in a different vase.

1484:

continued to use these sources and claimed them as reliable. Ortiz qualifies Harner's sources as

Spanish propaganda, and states the need to critique primary sources of interactions with the Aztecs. By dehumanizing and villainizing Aztec culture, the Spaniards were able to justify their own actions for conquest. Therefore, encounters with sacrificial cannibalism were said to be grossly exaggerated and Harner used the sources to aid his argument. However, it is unlikely that the Spanish conquerors would need to invent additional cannibalism to justify their actions given that human sacrifice already existed, as attested by archeological evidence. Overall, ecological factors alone are not sufficient to account for human sacrifice and, more recently, it is posited that religious beliefs have a significant effect on motivation.

262:

385:

551:"), and the god of the north. The Aztecs believed that Tezcatlipoca created war to provide food and drink to the gods. Tezcatlipoca was known by several epithets including "the Enemy" and "the Enemy of Both Sides", which stress his affinity for discord. He was also deemed the enemy of Quetzalcoatl, but an ally of Huitzilopochtli. Tezcatlipoca had the power to forgive sins and to relieve disease, or to release a man from the fate assigned to him by his date of birth; however, nothing in Tezcatlipoca's nature compelled him to do so. He was capricious and often brought about reversals of fortune, such as bringing drought and famine. He turned himself into

1566:

brave. Then, instead of being sacrificed honorably, their lowly death paralleled their new lowly status. Where one's body traveled in the afterlife also depended on the type of death awarded to the individual. Those who died while being sacrificed or while battling in war went to the second-highest heaven, while those who died of illness were the lowest in the hierarchy. Those going through the lowest hierarchy of death were required to undergo numerous torturous trials and journeys, only to culminate in a somber underworld. Additionally, death during Flower Wars was considered much more noble than death during regular military endeavors.

1466:

population pressure and an emphasis on maize agriculture, without domesticated herbivores, led to a deficiency of essential amino acids amongst the Aztecs. As population increased and the amount of available game decreased, the Aztecs had to compete with other carnivorous mammals, such as dogs, to find food. Harner believes that although intensified agricultural practices provided the Aztec society a surplus of carbohydrates, they did not provide sufficient nutritional balance; for this reason, the cannibalistic consumption of sacrificed humans was needed to supply an appropriate amount of protein per individual. Harris, author of

471:

19:

525:

681:

573:, a young impersonator of Tezcatlipoca would be sacrificed. Throughout a year, this youth would be dressed as Tezcatlipoca and treated as a living incarnation of the god. The youth would represent Tezcatlipoca on earth; he would get four beautiful women as his companions until he was killed. In the meantime he walked through the streets of Tenochtitlan playing a flute. On the day of the sacrifice, a feast would be held in Tezcatlipoca's honor. The young man would climb the pyramid, break his flute and surrender his body to the priests. Sahagún compared it to the Christian

1272:, Juan Díaz, Bernal Díaz, Andrés de Tapia, Francisco de Aguilar, Ruy González and the Anonymous Conqueror detailed their eyewitness accounts of human sacrifice in their writings about the Conquest of the Aztec Empire. However, as the conquerors often used such accounts to portray the Aztecs in a negative light, and thus justifying their colonization, the accuracy of these sources has been called into question. Martyr d'Anghiera, Lopez de Gomara, Oviedo y Valdes and Illescas, while not in Mesoamerica, wrote their accounts based on interviews with the participants.

137:

1444:

249:

the enemy from afar. During the flower wars, warriors were expected to fight up close and exhibit their combat abilities while aiming to injure the enemy, rather than kill them. The main objective of Aztec flower warfare was to capture victims alive for later ritual execution, and offerings to the gods. Being killed in the flower wars, which was considered much more noble than dying in a regular military battle, was religiously more prestigious, as these dead were given the privilege to live in heaven with the war god, Huitzilopochtli.

377:, to be an exaggeration. Hassig states "between 10,000 and 80,400 persons" were sacrificed in the ceremony. The higher estimate would average 15 sacrifices per minute during the four-day consecration. Four tables were arranged at the top so that the victims could be jettisoned down the sides of the temple. Additionally, some historians argue that these numbers were inaccurate as most written account of Aztec sacrifices were made by Spanish sources to justify Spain's conquest. Nonetheless, according to

1493:

504:

Sun-God. The body would then be pushed down the pyramid where the

Coyolxauhqui stone could be found. The Coyolxauhqui Stone recreates the story of Coyolxauhqui, Huitzilopochtli's sister who was dismembered at the base of a mountain, just as the sacrificial victims were. The body would be carried away and either cremated or given to the warrior responsible for the capture of the victim. He would either cut the body in pieces and send them to important people as an

353:

1213:

1476:

including meat from salamanders, fowls, armadillos, and weasels. These resources were also plenty available due to their need to subsist in Lake

Texcoco, the place where the Aztecs had created their home. In addition, even if no herbivores were available to eat, the nutrients needed were found in the leaves and seeds of amaranth which also provided protein. Lastly, the Aztecs had a highly structured system in which

3575:

245:, Huexotzingo and Cholula. This form of ritual was introduced probably after the mid-1450s following droughts, as famine caused many deaths in the Mexican highlands. The droughts and damage to crops were believed to be punishment by gods who felt unappreciated and improperly honored. Therefore, the flower wars provided victims for human sacrificial offerings in a highly structured and ceremonial manner.

258:

had been captured and prepared to be sacrificed. Even enemies of the Aztecs understood their roles as sacrifices to the gods since many also practiced the same type of religion. For many rites, the victims were expected to bless children, greet and cheer passers-by, hear people's petitions to the gods, visit people in their homes, give discourses and lead sacred songs, processions and dances.

1245:. A contrast is offered in the few Aztec statues that depict sacrificial victims, which show an Aztec understanding of sacrifice. Rather than showing a preoccupation with debt repayment, they emphasize the mythological narratives that resulted in human sacrifices, and often underscore the political legitimacy of the Aztec state. For instance, the

203:

extremely malevolent supernatural force. To avoid such calamities befalling their community, those who had erred punished themselves by extreme measures such as slitting their tongues for vices of speech or their ears for vices of listening. Other methods of atoning wrongdoings included hanging themselves, or throwing themselves down precipices.

441:

society who had fallen into debt or committed some crime. Likewise, most of the earliest accounts talk of prisoners of war of diverse social status, and concur that virtually all child sacrifices were locals of noble lineage, offered by their own parents. That women and children were not excluded from potential victims is attested by a

1562:(merchants), commoners and farmers. Then the lowest level of the hierarchy consisted of slaves and indentured servants. The only way of achieving social mobility was through successful performance as a warrior. This shows how important capturing enemies for sacrifice was as it was the singular way of achieving some type of "nobility".

2810:

aquellos ídolos los abren vivos por los pechos y les sacan el corazón y las entrañas, y queman las dichas entrañas y corazones delante de los ídolos, y ofreciéndolos en sacrificio aquel humo. Esto habemos visto algunos de nosotros, y los que lo han visto dicen que es la más cruda y espantosa cosa de ver que jamás han visto.

1361:, would complain on numerous occasions to Cortés about the perennial need to supply the Aztecs with victims for human sacrifice. It is clear from his description of their fear and resentment toward the Mexicas that, in their opinion, it was no honor to surrender their kinsmen to be sacrificed by them.

1565:

Within the system of organization based on hierarchy, there was also a social expectation contributing to the status of an individual at the time of their sacrifice. An individual was punished if unable to confidently address their own sacrifice, i.e. the person acted cowardly beforehand instead of

1536:

Posthumously, their remains were treated as actual relics of the gods which explains why victims' skulls, bones and skin were often painted, bleached, stored and displayed, or else used as ritual masks and oracles. For example, Diego Duran's informants told him that whoever wore the skin of the

1465:

Different anthropological or other sources have attempted to provide a possible ecological explanation of the need for human sacrifices to supplement overall Aztec diet. Harner's main argument lies within his claim that cannibalism is needed to assist the diet of the Aztecs. He claimed that very high

1307:

When he reached said tower the

Captain asked him why such deeds were committed there and the Indian answered that it was done as a kind of sacrifice and gave to understand that the victims were beheaded on the wide stone; that the blood was poured into the vase and that the heart was taken out of the

734:

appeared it meant that the sacrifices for this cycle had been enough. A fire was ignited on the body of a victim, and this new fire was taken to every house, city, and town. Rejoicing was general: a new cycle of 52 years was beginning and the end of the world had been postponed, at least for another

670:

According to the accounts of some, they assembled the children whom they slew in the first month, buying them from their mothers. And they went on killing them in all the feasts which followed, until the rains really began. And thus they slew some on the first month, named

Quauitleua; and some in the

1532:

victims were honored, hallowed and addressed very highly. Particularly the young man who was indoctrinated for a year to submit himself to

Tezcatlipoca's temple was the Aztec equivalent of a celebrity, being greatly revered and adored to the point of people "kissing the ground" when he passed by.

1509:

Sacrifices were ritualistic and symbolic acts accompanying huge feasts and festivals, and were a way to properly honor the gods. Victims usually died in the "center stage" amid the splendor of dancing troupes, percussion orchestras, elaborate costumes and decorations, carpets of flowers, crowds

1352:

They strike open the wretched Indian's chest with flint knives and hastily tear out the palpitating heart which, with the blood, they present to the idols ... They cut off the arms, thighs and head, eating the arms and thighs at ceremonial banquets. The head they hang up on a beam, and the body

420:

tool. The same can be said for Bernal Díaz's inflated calculations when, in a state of visual shock, he grossly miscalculated the number of skulls at one of the seven

Tenochtitlan tzompantlis. The counter argument is that both the Aztecs and Diaz were very precise in the recording of the many other

257:

Human sacrifice rituals were performed at the appropriate times each month or festival with the appropriate number of living bodies and other goods. These individuals were previously chosen to be sacrificed, as was the case for people embodying the gods themselves, or members of an enemy party which

1406:

They have a most horrid and abominable custom which truly ought to be punished and which until now we have seen in no other part, and this is that, whenever they wish to ask something of the idols, in order that their plea may find more acceptance, they take many girls and boys and even adults, and

1368:

Every day we saw sacrificed before us three, four or five

Indians whose hearts were offered to the idols and their blood plastered on the walls, and their feet, arms and legs of the victims were cut off and eaten, just as in our country we eat beef bought from the butchers. I even believe that they

456:

It is doubtful if many victims came from far afield. In 1454, the Aztec government forbade the slaying of captives from distant lands at the capital's temples. Duran's informants told him that sacrifices were consequently 'nearly always ... friends of the House' – meaning warriors from allied

436:

Every Aztec warrior would have to provide at least one prisoner for sacrifice. All the male population was trained to be warriors, but only the few who succeeded in providing captives could become full-time members of the warrior elite. Accounts also state that several young warriors could unite to

248:

This type of warfare differed from regular political warfare, as the flower wars were also an opportunity for combat training and as first exposure to combat for new soldiers. In addition, regular warfare included the use of long range weapons such as atlatl darts, stones, and sling shots to damage

202:

It is debated whether these rites functioned as a type of atonement for Aztec believers. Some scholars argue that the role of sacrifice was to assist the gods in maintaining the cosmos, and not as an act of propitiation. Aztec society viewed even the slightest tlatlacolli ('sin' or 'insult') as an

1421:

They lead him to the temple, where they dance and carry on joyously, and the man about to be sacrificed dances and carries on like the rest. At length the man who offers the sacrifice strips him naked, and leads him at once to the stairway of the tower where is the stone idol. Here they stretch

1381:

Cortes thanked them and made much of them, and we continued our march and slept in another small town, where also many sacrifices had been made, but as many readers will be tired of hearing of the great number of Indian men and women whom we found sacrificed in all the towns and roads we passed, I

440:

There is still much debate as to what social groups constituted the usual victims of these sacrifices. It is often assumed that all victims were 'disposable' commoners or foreigners. However, slaves – a major source of victims – were not a permanent class but rather persons from any level of Aztec

281:

A great deal of cosmological thought seems to have underlain each of the Aztec sacrificial rites. Most of the sacrificial rituals took more than two people to perform. In the usual procedure of the ritual, the sacrifice would be taken to the top of the temple. The sacrifice would then be laid on a

108:

A wide variety of interpretations of the Aztec practice of human sacrifice have been proposed by modern scholars. Many scholars now believe that Aztec human sacrifice, especially during troubled times like pandemic or other crises, was performed in honor of the gods. Most scholars of Pre-Columbian

2809:

Y tienen otra cosa horrible y abominable y digna de ser punida que hasta hoy no habíamos visto en ninguna parte, y es que todas las veces que alguna cosa quieren pedir a sus ídolos para que más acepten su petición, toman muchas niñas y niños y aun hombre y mujeres de mayor edad, y en presencia de

1475:

However, Bernard Ortiz

Montellano offers a counter argument and points out the faults of Harner's sources. First off, Ortiz challenges Harner's claim of the Aztecs needing to compete with other carnivorous mammals for protein packed food. Many other types of foods were available to the Aztecs,

1434:

Other human remains found in the Great Temple of

Tenochtitlan contribute to the evidence of human sacrifice through osteologic information. Indentations in the rib cage of a set of remains reveal the act of accessing the heart through the abdominal cavity, which correctly follows images from the

1483:

Ortiz's argument helps to frame and evaluate the gaps within Harner's argument. Part of the issue with Harner's reasoning for Aztec use of cannibalism was the lack of reliability of his sources. Harner recognized the numbers he used may be contradicting or conflicting with other sources, yet he

1224:

Visual accounts of Aztec sacrificial practice are principally found in codices and some Aztec statuary. Many visual renderings were created for Spanish patrons, and thus may reflect European preoccupations and prejudices. Produced during the 16th century, the most prominent codices include the

705:

dress and live as Xipe Totec. The victims were then taken to the Xipe Totec's temple where their hearts would be removed, their bodies dismembered, and their body parts divided up to be later eaten. Prior to death and dismemberment the victim's skin would be removed and worn by individuals who

503:

When the Aztecs sacrificed people to Huitzilopochtli (the god with warlike aspects) the victim would be placed on a sacrificial stone. The priest would then cut through the abdomen with an obsidian or flint blade. The heart would be torn out still beating and held towards the sky in honor to the

1549:

Politically, human sacrifice was important in Aztec culture as a way to represent a social hierarchy between their own culture and the enemies surrounding their city. Additionally, it was a way to structure the society of the Aztec culture itself. The hierarchy of cities like Tenochtitlan were

1343:

Díaz recounted that, after landing on the coast, they came across a temple dedicated to Tezcatlipoca. "That day they had sacrificed two boys, cutting open their chests and offering their blood and hearts to that accursed idol". Díaz narrates several more sacrificial descriptions on the later

515:

During the festival of Panquetzaliztli, of which Huitzilopochtli was the patron, sacrificial victims were adorned in the manner of Huitzilopochtli's costume and blue body paint, before their hearts would be sacrificially removed. Representations of Huitzilopochtli called teixiptla were also

1407:

in the presence of these idols they open their chests while they are still alive and take out their hearts and entrails and burn them before the idols, offering the smoke as sacrifice. Some of us have seen this, and they say it is the most terrible and frightful thing they have ever witnessed.

630:) rose over the mountain, a man would be sacrificed. The victim's heart would be ripped from his body and a ceremonial hearth would be lit in the hole in his chest. This flame would then be used to light all of the ceremonial fires in various temples throughout the city of Tenochtitlan.

1330:

On these altars were idols with evil looking bodies, and that every night five Indians had been sacrificed before them; their chests had been cut open, and their arms and thighs had been cut off. The walls were covered with blood. We stood greatly amazed and gave the island the name

173:(also called "Motolinía") observed that the Aztecs gladly parted with everything. Even the "stage" for human sacrifice, the massive temple-pyramids, was an offering mound: crammed with the land's finest art, treasure and victims; they were then buried underneath for the deities.

1523:

For each festival, at least one of the victims took on the paraphernalia, habits, and attributes of the god or goddess whom they were dying to honor or appease. Through this performance, it was said that the divinity had been given 'human form'—that the god now had an

339:

Those individuals who were unable to complete their ritual duties were disposed of in a much less honorary matter. This "insult to the gods" needed to be atoned, therefore the sacrifice was slain while being chastised instead of revered. The conquistadors Cortés and

647:

is the god of rain, water, and earthly fertility. The Aztecs believed that if sacrifices were not supplied for Tlaloc, rain would not come, their crops would not flourish, and leprosy and rheumatism, diseases caused by Tlaloc, would infest the village.

655:. Many of the children suffered from serious injuries before their death, they would have to have been in significant pain as Tlaloc required the tears of the young as part of the sacrifice. The priests made the children cry during their way to

1348:, they find "cages of stout wooden bars ... full of men and boys who were being fattened for the sacrifice at which their flesh would be eaten". When the conquistadors reached Tenochtitlan, Díaz described the sacrifices at the Great Pyramid:

306:. The priest would rip out the heart and it would then be placed in a bowl held by a statue of the honored god, and the body would then be thrown down the temple's stairs. The body would land on a terrace at the base of the pyramid called an

313:

Before and during the killing, priests and audience, gathered in the plaza below, stabbed, pierced and bled themselves as auto-sacrifice. Hymns, whistles, spectacular costumed dances and percussive music marked different phases of the rite.

415:

argues that a claim by Don Carlos Zumárraga of 20,000 per annum is "more plausible". Other scholars believe that, since the Aztecs often tried to intimidate their enemies, it is more likely that they could have inflated the number as a

606:, the fire god and a senior deity, the Aztecs had a ceremony where they prepared a large feast, at the end of which they would burn captives; before they died they would be taken from the fire and their hearts would be cut out.

725:

The cycle of 52 years was central to Mesoamerican cultures. The Nahua's religious beliefs were based on a great fear that the universe would collapse after each cycle if the gods were not strong enough. Every 52 years a special

489:. He was considered the primary god of the south and a manifestation of the sun, and a counterpart of the black Tezcatlipoca, the primary god of the north, "a domain associated with Mictlan, the underworld of the dead".

157:

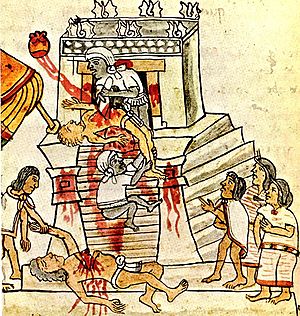

What the Aztec priests were referring to was a cardinal Mesoamerican belief: that a great and continuing sacrifice by the gods sustains the Universe. A strong sense of indebtedness was connected with this worldview. Indeed,

191:

by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún reports that in one of the creation myths, Quetzalcóatl offered blood extracted from a wound in his own penis to give life to humanity. There are several other myths in which

61:(1200–400 BC), and perhaps even throughout the early farming cultures of the region. However, the extent of human sacrifice is unknown among several Mesoamerican civilizations. What distinguished Aztec practice from

701:, in which captured warriors and slaves were sacrificed in the ceremonial center of the city of Tenochtitlan. For forty days prior to their sacrifice one victim would be chosen from each ward of the city to act as

433:(INAH), discovered a skull rack and skull towers next to the Templo Mayor complex that could have held thousands of skulls. However, as of 2020, only 603 skulls have ever been found associated with human sacrifice.

323:

or the skull rack. When the consumption of individuals was involved, the warrior who captured the enemy was given the meaty limbs while the most important flesh, the stomach and chest, were offerings to the gods.

327:

Other types of human sacrifice, which paid tribute to various deities, killed the victims differently. The victim could be shot with arrows, die in gladiatorial style fighting, be sacrificed as a result of the

671:

second, named Tlacaxipeualiztli; and some in the third, named Tocoztontli; and others in the fourth, named Ueitocoztli; so that until the rains began in abundance, in all the feasts they sacrificed children.

485:

and, as such, he represented the character of the Mexican people and was often identified with the sun at the zenith, and with warfare, who burned down towns and carried a fire-breathing serpent,

3035:

2824:

1413:

425:, fifty years before the conquest the Aztecs burnt the skulls of the former tzompantli. Archeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma has unearthed and studied some tzompantlis. In 2003, archaeologist

1364:

At the town of Cingapacigna Cortez told the chiefs that for them to become friends and brothers of the Spaniards they must end the practice of making sacrifices. According to Bernal Díaz:

610:

and Sahagún reported that the Aztecs believed that if they did not placate Huehueteotl, a plague of fire would strike their city. The sacrifice was considered an offering to the deity.

1472:, has propagated the claim originally proposed by Harner, that the flesh of the victims was a part of an aristocratic diet as a reward, since the Aztec diet was lacking in proteins.

558:

Some captives were sacrificed to Tezcatlipoca in ritual gladiatorial combat. The victim was tethered in place and given a mock weapon. He died fighting against up to four fully armed

133:

confronted the remaining Aztec priesthood and demanded, under threat of death, that they desist from this traditional practice. The Aztec priests defended themselves as follows:

97:, and other archaeological sites, have provided physical evidence of human sacrifice among the Mesoamerican peoples. As of 2020, archaeologists have found 603 human skulls at the

555:, the god of the hunt, to make fire. To the Aztecs, he was an all-knowing, all-seeing nearly all-powerful god. One of his names can be translated as "He Whose Slaves We Are".

187:

thorns, tainted with their own blood and would offer blood from their tongues, ear lobes, or genitals. Blood held a central place in Mesoamerican cultures. The 16th-century

2619:

1391:

Cortés was the Spanish conquistador whose expedition to Mexico in 1519 led to the fall of the Aztecs, and led to the conquering of vast sections of Mexico on behalf of the

1024:

Sacrifice of a decapitated young woman to Toci; she was skinned and a young man wore her skin; sacrifice of captives by hurling from a height and extraction of the heart

199:

Another theory is that human sacrifice was used to supply protein and other vital nutrients in the absence of large game animals, though this argument is controversial.

2970:

169:

Human sacrifice was in this sense the highest level of an entire panoply of offerings through which the Aztecs sought to repay their debt to the gods. Both Sahagún and

1308:

breast and burnt and offered to the said idol. The fleshy parts of the arms and legs were cut off and eaten. This was done to the enemies with whom they were at war.

1261:; it also, as Cecelia Kline has pointed out, "served to warn potential enemies of their certain fate should they try to obstruct the state's military ambitions".

429:

noted that the largest number of skulls yet found at a single tzompantli was only about a dozen. In 2015, Raùl Barrera Rodríguez, archeologist and director of the

3102:

81:

2096:

Doubleday, New York, pp. 194–195. Hanson, who accepts the 80,000+ estimate, also notes that it exceeded "the daily murder record at either Auschwitz or Dachau".

742:

and Motolinía report that the Aztecs had 18 festivities each year, one for each Aztec month. The table below shows the festivals of the 18-month year of the

381:, old Aztecs who talked with the missionaries told about a much lower figure for the reconsecration of the temple, approximately 4,000 victims in total.

1792:

403:

of the number of persons sacrificed in central Mexico in the 15th century as high as 250,000 per year, which may have been one percent of the population.

206:

What has been gleaned from all of this is that the sacrificial role entailed a great deal of social expectation and a certain degree of acquiescence.

430:

4202:

1764:

599:

For ten days preceding the festival various animals would be captured by the Aztecs, to be thrown in the hearth on the night of celebration.

3442:

65:

was the way in which it was embedded in everyday life. These cultures also notably sacrificed elements of their own population to the gods.

4417:

2923:

373:

in 1487, the Aztecs sacrificed about 80,400 prisoners over the course of four days. This number is considered by Ross Hassig, author of

153:

Life is because of the gods; with their sacrifice, they gave us life. ... They produce our sustenance ... which nourishes life.

2483:

Fernández 1992, 1996, pp. 60–63. Matos Moctezuma 1988, p.181. Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, pp. 54–55. Neumann 1976, pp. 252.

317:

The body parts would then be disposed of, the viscera fed to the animals in the zoo, and the bleeding head was placed on display in the

176:

Additionally, the sacrifice of animals was a common practice, for which the Aztecs bred dogs, eagles, jaguars and deer. The cult of

3625:

1431:

Modern excavations in Mexico City have found evidence of human sacrifice in the form of hundreds of skulls at the site of old temples.

730:

was performed. All fires were extinguished and at midnight a human sacrifice was made. The Aztecs then waited for the sunrise. If the

3532:

1528:(face). Duran says such victims were 'worshipped ... as the deity' or 'as though they had been gods'. Even whilst still alive,

639:

622:

617:, which occurred every 52 years, and prevented the ending of the world. During the festival priests would march to the top of the

512:. The warrior would thus ascend one step in the hierarchy of the Aztec social classes, a system that rewarded successful warriors.

4192:

404:

3481:

4422:

344:

found that some of the sacrificial victims they freed "indignantly rejected offer of release and demanded to be sacrificed".

109:

civilization see human sacrifice among the Aztecs as a part of the long cultural tradition of human sacrifice in Mesoamerica.

4523:

3454:

3412:

3364:

3290:

3245:

Ingham, John M. "Human Sacrifice at Tenochtitln." Society for Comparative Studies in Society and History 26 (1984): 379–400.

3227:

3189:

3158:

3120:

3080:

2195:"A 500-Year-Old Aztec Tower of Human Skulls Is Even More Terrifyingly Humongous Than Previously Thought, Archaeologists Find"

90:

that relate to the testimonies of native eyewitnesses. The literary accounts have been supported by archeological research.

2645:

De Montellano, Bernard R. Ortiz (1983-06-01). "Counting Skulls: Comment on the Aztec Cannibalism Theory of Harner-Harris".

500:. The Templo Mayor consisted of twin pyramids, one for Huitzilopochtli and one for the rain god Tlaloc (discussed below).

126:

3308:

Ortiz De Montellano, Bernard R. (June 1983). "Counting Skulls: Comment on the Aztec Cannibalism Theory of Harner-Harris".

516:

worshipped, the most significant being the one at the Templo Mayor which was made of dough mixed with sacrificial blood.

261:

1292:

1186:

Sacrifices of victims representing Xiuhtecuhtli and their women (each four years), and captives; hour: night; New Fire

2320:

2194:

1585:

505:

4432:

2946:

1377:

On meeting a group of inhabitants from Cempoala who gave Cortés and his men food and invited them to their village:

1480:

and tribute provided a surplus of materials and therefore ensured the Aztec were able to meet their caloric needs.

4487:

4367:

4312:

2611:

1580:

302:

was a very important religious tool used during sacrifices. The cut was made in the abdomen and went through the

270:

62:

1460:

2363:

Boone, Elizabeth. "Incarnations of the Aztec Supernatural: The Image of Huitzilopochtli in Mexico and Europe".

1900:

607:

170:

1264:

In addition to the accounts provided by Sahagún and Durán, there are other important texts to be considered.

4407:

3525:

384:

370:

94:

3282:

2349:

2179:

1510:

of thousands of commoners, and all the assembled elite. Aztec texts frequently refer to human sacrifice as

286:, by four priests, and their abdomen would be sliced open by a fifth priest with a ceremonial knife made of

3258:

3219:

3150:

694:, known as "Our Lord the Flayed One", is the god of rebirth, agriculture, the seasons, and craftsmen.

57:

performed sacrifices as well and from archaeological evidence, it probably existed since the time of the

799:

Sacrifice of captives; gladiatorial fighters; dances of the priest wearing the skin of the flayed victims

474:

Techcatl — Mesoamerican sacrifice altar. Mexica room of the National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City).

4462:

3434:

3400:

548:

426:

3098:

77:

4267:

4227:

825:

Type of sacrifice: extraction of the heart; burying of the flayed human skins; sacrifices of children

4437:

2781:

2767:

2753:

2739:

1834:

1318:

1234:

378:

80:, who participated in the Cortés expedition, made frequent mention of human sacrifice in his memoir

18:

4307:

4282:

2804:

2717:

Historia verdadera de la conquista de Nueva España (Introducción y notas de Joaquín Ramírez Cabañas)

1273:

229:'s History of the Indies of New Spain (and a few other sources that are believed to be based on the

4528:

3518:

3404:

3356:

2821:

1604:

1345:

290:. The most common form of human sacrifice was heart-extraction. The Aztec believed that the heart (

4342:

3712:

3382:

2285:

1064:-Napatecuhtli, Matlalcueye, Xochitécatl, Mayáhuel, Milnáhuatl, Napatecuhtli, Chicomecóatl,

995:, Ixcozauhqui, Otontecuhtli, Chiconquiáhitl, Cuahtlaxayauh, Coyolintáhuatl, Chalmecacíhuatl

543:

was generally considered the most powerful god, the god of night, sorcery and destiny (the name

437:

capture a single prisoner, which suggests that capturing prisoners for sacrifice was challenging.

163:

141:

4151:

3310:

3274:

3039:

1735:

524:

470:

148:

and reuniting it with the Sun: the victim's transformed heart flies Sun-ward on a trail of blood.

3595:

3250:

3043:

1969:

4518:

4327:

4012:

4007:

2902:

1793:"Feeding the gods: Hundreds of skulls reveal massive scale of human sacrifice in Aztec capital"

1299:

before 1520, in which he describes the aftermath of a sacrifice on an island off the coast of

739:

242:

4387:

3559:

2107:

680:

4467:

3821:

3390:

2126:

1291:

was one of the first Spaniards to explore Mexico and traveled on his expedition in 1518 with

627:

329:

273:. This altar-like stone vessel was used to hold the hearts of sacrificial victims. See also

238:

4352:

3563:

2797:

1747:

1541:(Our Lord the Flayed One) felt he was wearing a holy relic. He considered himself 'divine'.

4497:

4477:

4457:

4447:

4442:

4377:

4357:

4337:

4322:

4317:

4292:

4197:

4172:

4002:

3257:. Civilization of the American Indian series, #67. Translated by Jack Emory Davis. Norman:

1684:

1637:

1238:

529:

42:

2827:, México, Chapter XV, written by a Companion of Hernán Cortés, The Anonymous Conquistador.

2534:

651:

Archaeologists have found the remains of at least 42 children sacrificed to Tlaloc at the

46:

8:

4382:

4297:

4146:

3729:

3702:

3653:

1468:

412:

408:

3663:

3149:. Civilization of the American Indian series, #210. Translated by Doris Heyden. Norman:

2249:

1641:

125:", all the gods sacrificed themselves so that mankind could live. Some years after the

4237:

3966:

3826:

3806:

3633:

3583:

3349:

3335:

3212:

2878:

2670:

2510:

1938:

1703:

1653:

1269:

1070:

Sacrifices of children, two noble women, extraction of the heart and flaying; ritual

421:

details of Aztec life, and inflation or propaganda would be unlikely. According to the

303:

69:

1443:

706:

traveled throughout the city fighting battles and collecting gifts from the citizens.

4482:

4287:

4118:

3946:

3901:

3801:

3761:

3460:

3450:

3418:

3408:

3386:

3370:

3360:

3339:

3327:

3296:

3286:

3262:

3233:

3223:

3195:

3185:

3164:

3154:

3126:

3116:

3086:

3076:

3049:

2952:

2942:

2870:

2674:

2662:

2514:

2326:

2316:

1896:

1707:

1071:

943:

727:

614:

509:

341:

136:

3786:

3493:

2882:

1942:

86:. There are a number of second-hand accounts of human sacrifices written by Spanish

4452:

4272:

4212:

4182:

4177:

4108:

3871:

3831:

3751:

3692:

3680:

3446:

3394:

3319:

2862:

2697:

2654:

2502:

1930:

1693:

1645:

1501:

1392:

1288:

1265:

1242:

936:

422:

188:

38:

4397:

4113:

3323:

2866:

2701:

2658:

1628:

Diaz de Castillo, Bernal (1917). "The True History of the Conquest of New Spain".

411:, estimated that one in five children of the Mexica subjects was killed annually.

76:

and made observations of and wrote reports about the practice of human sacrifice.

4347:

4277:

4242:

4063:

3836:

3771:

3658:

3643:

3541:

3045:

Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitan, México

2313:

Quetzalcoatl and the irony of empire: myths and prophecies in the Aztec tradition

1698:

1679:

1112:

1105:

973:

965:

911:

871:

793:

478:

184:

26:

3956:

3791:

2493:

Carrasco, David (1995). "Give Me Some Skin: The Charisma of the Aztec Warrior".

1514:, "the desire to be regarded as a god". These members of the society became an

1065:

1040:

4392:

4222:

3856:

1575:

1448:

1411:

The Anonymous Conquistador was an unknown travel companion of Cortés who wrote

886:

743:

715:

656:

588:

is the god of fire and heat and in many cases is considered to be an aspect of

563:

559:

392:

4262:

4187:

4037:

3911:

3138:

2971:

Aztec human sacrifice: Cross-cultural assessments of the ecological hypothesis

1921:

Isaac, Barry L (1983). "The Aztec "Flowery War": A Geopolitical Explanation".

1447:

Aztec or Mixtec sacrificial knife, probably for ceremonial use only, in the

1323:

226:

4512:

4257:

4032:

3851:

3846:

3816:

3811:

3776:

3766:

3555:

3445:(photographer) (2nd paperback, reprint with corrections ed.). New York:

3181:

3130:

3112:

2903:"Human Sacrifice and Mortuary Treatments in the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan"

2666:

1934:

1357:

According to Bernal Díaz, the chiefs of the surrounding towns, for example

1153:

918:

834:

536:(sword/club) is covered with what appears to be feathers instead of obsidian.

400:

193:

4412:

3951:

3697:

3464:

3396:

Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, 13 vols. in 12

3374:

3300:

3237:

3199:

3168:

3090:

3069:

City of Sacrifice: The Aztec Empire and the Role of Violence in Civilization

2956:

1866:

1398:

Cortés wrote of Aztec sacrifice on numerous occasions, one of which in his

1226:

1163:

Sacrifice of a woman by extraction of the heart and decapitation afterwards

4492:

4472:

4332:

4217:

4207:

4083:

4047:

3976:

3916:

3906:

3717:

3685:

3605:

3600:

3430:

3331:

3142:

3072:

3053:

2874:

2330:

1492:

1250:

1246:

1230:

1217:

1180:

1157:

992:

969:

958:

897:

867:

846:

652:

585:

540:

497:

493:

450:

446:

431:

Urban Archaeology Program at National Institute of Anthropology and History

266:

177:

118:

102:

73:

54:

3422:

3266:

1558:) next who managed the land owned by the emperor. Then the warriors, the

1280:

but had access to direct testimony, especially of the indigenous people.

230:

166:

reported, it was said that the victim was someone who "gave his service".

162:(debt-payment) was a commonly used metaphor for human sacrifice, and, as

4427:

4402:

4372:

4362:

4252:

4247:

4232:

4167:

4123:

4103:

4078:

3981:

3961:

3921:

3707:

3504:

3207:

3108:

2838:

Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitan

2825:

Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitan

1414:

Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitan

1054:

1007:

808:

603:

595:

Both Xiuhtecuhtli and Huehueteotl were worshipped during the festival of

589:

363:

220:

130:

30:

4017:

3722:

3638:

3178:

One Cosmos under God: The Unification of Matter, Life, Mind & Spirit

294:) was both the seat of the individual and a fragment of the Sun's heat (

4302:

4098:

4073:

4042:

4022:

3997:

3781:

3610:

2404:

López Austin 1998, p.10. Sahagún 1577, 1989, p.48 (Book I, Chapter XIII

1657:

1538:

1201:

Five ominous days at the end of the year, no ritual, general fasting

922:

691:

684:

533:

442:

417:

358:

319:

234:

98:

4088:

144:, Folio 70. Heart-extraction was viewed as a means of liberating the

4141:

4027:

3941:

3936:

3841:

1516:

1277:

1258:

1254:

1194:

1126:

1117:

Massive sacrifices of captives and slaves by extraction of the heart

1090:

1082:

1018:

815:

659:: a good omen that Tlaloc would wet the earth in the raining season.

496:, which was the primary religious structure of the Aztec capital of

486:

122:

4068:

3675:

2533:(1997). Wired humanities project. Retrieved September 2, 2012, from

2082:. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University.

1649:

1133:

1096:

Sacrifice by bludgeoning, decapitation and extraction of the heart

1061:

893:

772:

352:

3896:

3881:

3876:

3861:

3756:

3746:

3648:

3614:

3048:. Translated by Marshall H. Saville. New York: The Cortes Society.

2506:

1765:"The Aztecs Constructed This Tower Out of Hundreds of Human Skulls"

1417:

which details Aztec sacrifices. The Anonymous Conquistador wrote,

1358:

1300:

1253:

commemorates the mythic slaying of Huitzilopochli's sister for the

1212:

1033:

552:

274:

3510:

3500:

3926:

3886:

3866:

3796:

3741:

1172:

949:

Sacrifice by decapitation of a woman and extraction of her heart

860:

618:

570:

369:

Some post-conquest sources report that at the re-consecration of

333:

2853:

Wade, Lizzie (2018). "Aztec Human Sacrifice: Feeding the Gods".

3971:

3891:

3574:

3346:

3307:

3218:. Civilization of the American Indian series, no. 188. Norman:

1386:

842:

819:

644:

574:

482:

58:

50:

34:

3429:

3255:

Aztec Thought and Culture: A Study of the Ancient Náhuatl Mind

1967:

Hassig, Ross (2003). "El sacrificio y las guerras floridas".

1426:

1382:

shall go on with my story without saying any more about them.

697:

Xipe Totec was worshipped extensively during the festival of

287:

87:

2437:

Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain

2108:"Human Sacrifice: Why the Aztecs Practiced This Gory Ritual"

347:

3931:

1014:

93:

Since the late 1970s, excavations of the offerings in the

2612:"Fighting with Femininity: Gender and War in Aztec Mexico"

746:

and the deities with which the festivals were associated.

3381:

3097:

2382:

2380:

2378:

731:

183:

Self-sacrifice was also quite common; people would offer

3273:

1496:

A ceremonial offering of Aztec sacrificial knife blades

778:

Sacrifice of children and captives to the water deities

180:

required the sacrifice of butterflies and hummingbirds.

3214:

Aztec Warfare: Imperial Expansion and Political Control

1850:

Atrocities: The 100 Deadliest Episodes in Human History

755:

Name of the Mexican month and its Gregorian equivalent

2375:

2250:"Aztec tower of human skulls uncovered in Mexico City"

1435:

codices in the pictorial representation of sacrifice.

3249:

1673:

1671:

1669:

1667:

1505:

at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City

112:

2688:

Nuttall, Zelia (1910). "The Island of Sacrificios".

3034:

2450:

The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya

1520:—that is, a god's representative, image or idol.

998:Sacrifices to the fire gods by burning the victims

3348:

3211:

2939:Cannibals and kings : the origins of cultures

2796:

2365:Transactions of the American Philosophical Society

1895:. University of Michigan: Zone. pp. 367–385.

1664:

1138:Sacrifices of children and slaves by decapitation

902:Sacrifice by drowning and extraction of the heart

3175:

3111:(6th printing ed.). Harmondsworth, England:

1819:Ingham, John M. "Human Sacrifice at Tenochtitlan"

1283:

946:, Quilaztli-Cihacóatl, Ehécatl, Chicomelcóatl

877:Sacrifice of captives by extraction of the heart

738:Sacrifices were made on specific days. Sahagún,

528:Victim of sacrificial gladiatorial combat, from

362:, or skull rack, as shown in the post-Conquest

4510:

3399:. vols. I-XII. Santa Fe, NM and Salt Lake City:

2415:Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España

2290:Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España

1748:"Grisly Sacrifices Found in Pyramid of the Moon"

1627:

532:. Note that he is tied to a large stone and his

3066:

2900:

2564:Motolinia's History of the Indians of New Spain

2173:

1720:

3439:Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art

1987:

1093:, Izquitécatl, Yoztlamiyáhual, Huitznahuas

1017:, Teteoinan, Chimelcóatl-Chalchiuhcíhuatl,

460:

3526:

2644:

2452:. Thames and Hudson Inc. p. 166-167, 142–143.

2346:La flor letal: economía del sacrificio azteca

2269:

2267:

2118:

2073:

2071:

1554:(emperor) on the top, the remaining nobles (

626:and when the constellation "the fire drill" (

3479:

3206:

3137:

1815:

1813:

1387:Hernán Cortés and the Anonymous Conquistador

1045:Sacrifices by fire; extraction of the heart

978:Sacrifice by starvation in a cave or temple

613:Xiuhtecuhtli was also worshipped during the

45:. Other Mesoamerican cultures, such as the

3021:Peregrine, Peter N, and Melvin Ember. 2002.

2080:State and Cosmos in the Art of Tenochtitlan

580:

3533:

3519:

3281:(in Spanish) (3rd ed.). México D.F.:

3012:Peregrine, Peter N, and Melvin Ember. 2002

2546:

2465:. Fondo de cultura económica. pp. 128–129.

2264:

2068:

1736:"Evidence May Back Human Sacrifice Claims"

1680:"The Ecological Basis for Aztec Sacrifice"

1427:Archaeological evidence of human sacrifice

664:General History of the Things of New Spain

2963:

2561:

2002:Sahagun Bk 5: 8; Bk 2: 5:9; Bk 2:24:68–69

1828:

1810:

1697:

1461:Cannibalism in the Americas § Aztecs

1454:

1021:, Atlauhaco, Chiconquiáuitl, Cintéotl

640:Child sacrifice in pre-Columbian cultures

592:, the "Old God" and another fire deity.

348:Scope of human sacrifice in Aztec culture

196:gods offer their blood to help humanity.

83:True History of the Conquest of New Spain

3347:Ortiz De Montellano, Bernard R. (1990).

2492:

2343:

2315:. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

2310:

2077:

1890:

1831:(in) Handbook of Middle American Indians

1544:

1491:

1487:

1442:

1438:

1211:

709:

679:

662:In the Florentine Codex, also known as

523:

469:

407:, a Mexica descendant and the author of

383:

351:

260:

135:

17:

4418:Romances de los señores de Nueva España

2687:

2192:

1852:. W.W. Norton and Company. p. 158.

22:Prisoners for sacrifice were decorated.

4511:

3147:The History of the Indies of New Spain

2936:

2848:

2846:

2794:

2526:

2524:

2244:

2242:

2124:

1966:

1677:

1500:

492:Huitzilopochtli was worshipped at the

209:

33:, so the rite was nothing new to the

3514:

3482:"El sacrificio humano en Mesoamérica"

3351:Aztec Medicine, Health, and Nutrition

2896:

2894:

2892:

2640:

2638:

2636:

2634:

2609:

2590:

2588:

2042:

2040:

2038:

2036:

2034:

2032:

2030:

2028:

2026:

2010:

2008:

1962:

1960:

1958:

1956:

1954:

1952:

1920:

1916:

1914:

1912:

1861:

1859:

1847:

1786:

1784:

1758:

1756:

927:Sacrifice by extraction of the heart

851:Sacrifice of a maid; of boy and girl

405:Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxochitl

336:after being sacrificed, or drowned.

2852:

2803:. México: Editorial Porrúa. p.

2714:

2435:Sahagun, Fray Bernardino de (1569).

1037:(from September 10 to September 29)

127:Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire

3540:

2843:

2594:

2576:

2521:

2239:

1990:Handbook to Life in the Aztec World

1923:Journal of Anthropological Research

1762:

1353:is ... given to the beasts of prey.

252:

13:

3107:. Penguin Classics. Translated by

2889:

2631:

2585:

2570:

2226:

2217:

2023:

2005:

1949:

1909:

1856:

1781:

1753:

1586:Human trophy taking in Mesoamerica

1326:corroborates Juan Díaz's history:

1207:

1130:(from November 29 to December 18)

1058:(from September 30 to October 19)

465:

237:were a ritual among the cities of

113:Role of sacrifice in Aztec culture

41:, nor was it something unique to

14:

4540:

4313:Lienzo de Coixtlahuaca I & II

3558:: Ometēcuthli and Omecihuātl (or

3473:

2362:

2174:Matos-Moctezuma, Eduardo (2005).

2017:The Aztecs: History of the Indies

2014:

1721:Matos-Moctezuma, Eduardo (1986).

1183:, Cihuatontli, Nancotlaceuhqui

1109:(from November 9 to November 28)

769:(from February 2 to February 21)

101:in the archeological zone of the

3573:

3279:Vida y muerte en el Templo Mayor

2901:Chavez Balderas, Ximena (2007).

2105:

2059:

1790:

1723:Vida y muerte en el Templo Mayor

1198:(from January 28 to February 1)

1149:(from December 19 to January 7)

1086:(from October 20 to November 8)

1011:(from August 21 to September 9)

720:

508:, or use the pieces for ritual

140:Human sacrifice as shown in the

117:Sacrifice was a common theme in

4488:Codex Vindobonensis Mexicanus I

4368:Oztoticpac Lands Map of Texcoco

4318:Lienzo de Santa María Nativitas

3027:

3015:

3006:

2993:

2980:

2930:

2924:"Website of the British Museum"

2916:

2830:

2815:

2788:

2774:

2760:

2746:

2732:

2723:

2719:. Editorial Porrúa. p. 24.

2708:

2681:

2603:

2555:

2549:Relación de Juan Bautista Pomar

2540:

2486:

2477:

2468:

2455:

2442:

2429:

2420:

2407:

2398:

2389:

2356:

2337:

2304:

2295:

2279:

2211:

2186:

2167:

2158:

2149:

2127:"The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice"

2099:

2086:

2053:

1996:

1992:. New York: Facts on File, Inc.

1988:Aguilar-Moreno, Manuel (2006).

1981:

1884:

1841:

1822:

1581:Human sacrifice in Maya culture

1344:Cortés expedition. Arriving at

1249:stone found at the foot of the

1176:(from January 8 to January 27)

789:(from February 22 to March 13)

519:

271:National Museum of Anthropology

72:conquered the Aztec capital of

4328:Lienzo de Zacatepec I & II

1741:

1729:

1714:

1621:

1597:

1312:

1284:Juan de Grijalva and Juan Díaz

214:

1:

3501:" The Custom of Aztec Burial"

3324:10.1525/aa.1983.85.2.02a00130

2977:Vol 37 No. 3 1998 pp. 285–298

2867:10.1126/science.360.6395.1288

2702:10.1525/aa.1910.12.2.02a00070

2659:10.1525/aa.1983.85.2.02a00130

2193:Cascone, Sarah (2020-12-16).

1725:. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

1537:victim who had portrayed god

1276:and Sahagún arrived later to

989:(from August 1 to August 20)

758:Deities and human sacrifices

675:

653:Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan

547:means "smoking mirror", or "

397:The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice

371:Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan

95:Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan

4524:Aztec mythology and religion

3259:University of Oklahoma Press

3220:University of Oklahoma Press

3151:University of Oklahoma Press

2461:Duverger, Christian (2005).

2344:Duverger, Christian (2005).

2092:Victor Davis Hanson (2000),

1891:Duverger, Christian (1989).

1829:Nicholson, Henry B. (1971).

1699:10.1525/ae.1977.4.1.02a00070

1591:

874:, Tlacahuepan, Cuexcotzin

841:Cintéotl, Chicomecacóatl,

481:was the tribal deity of the

29:was common in many parts of

7:

4463:Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca

4323:Lienzo de Santiago Ihuitlan

3492:(63): 16–21. Archived from

3401:School of American Research

3042:; Alec Christensen (eds.).

2620:Estudios de Cultura Nahuatl

2164:Duverger (op. cit), 174–177

2048:Book of the Gods and Rites,

1569:

1373:as they call their markets.

838:(from April 3 to April 22)

812:(from March 14 to April 2)

775:, Chalchitlicue, Ehécatl

569:During the 20-day month of

461:Sacrifices to specific gods

68:In 1519, explorers such as

10:

4545:

4423:Codex Santa Maria Asunción

4203:Boban Aztec Calendar Wheel

3283:Fondo de Cultura Económica

3176:Godwin, Robert W. (2004).

2988:Book of the Gods and Rites

2562:Andros Foster, Elizabeth.

2350:Fondo de Cultura Económica

2275:Book of the Gods and Rites

2180:Fondo de Cultura Económica

2176:Muerte a filo de obsidiana

2078:Townsend, Richard (1979).

1458:

1316:

962:(from July 12 to July 31)

940:(from June 22 to July 11)

864:(from April 23 to May 12)

713:

637:

218:

4438:Codex Telleriano-Remensis

4228:Mapas de Cuauhtinchan 1-4

4198:Codices Becker I & II

4160:

4132:

4056:

3990:

3624:

3582:

3571:

3548:

3104:The Conquest of New Spain

3099:Díaz del Castillo, Bernal

2782:The Conquest of New Spain

2768:The Conquest of New Spain

2754:The Conquest of New Spain

2740:The Conquest of New Spain

2386:Olivier (2003) pp. 14–15.

2062:The Conquest of New Spain

1835:University of Texas Press

1502:[tekpat͡ɬiʃˈkawa]

1369:sell it by retain in the

1341:The Conquest of New Spain

1319:The Conquest of New Spain

1200:

1089:Mixcóatl-Tlamatzincatl,

915:(from June 2 to June 21)

757:

633:

379:Codex Telleriano-Remensis

37:when they arrived at the

4378:Plano en papel de maguey

4188:Codices Azoyú I & II

3405:University of Utah Press

3357:Rutgers University Press

3275:Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo

3067:Carrasco, David (1999).

2836:Anonymous Conquistador.

2795:Cortés, Hernán (2005) .

2395:Sahagún, Op. cit., p. 79

2311:Carrasco, David (1982).

2125:Harner, Michael (1977).

1935:10.1086/jar.39.4.3629865

1893:The Meaning of Sacrifice

1678:Harner, Michael (1977).

1630:The Geographical Journal

890:(from May 13 to June 1)

822:, Chalchitlicue, Tona

581:Huehueteotl/Xiuhtecuhtli

78:Bernal Díaz del Castillo

4173:Aubin Manuscript no. 20

3311:American Anthropologist

2937:Harris, Marvin (1978).

2729:Díaz (op. cit.), p. 150

2690:American Anthropologist

2647:American Anthropologist

2610:Klein, Cecelia (1994).

2413:Bernardino de Sahagún,

2252:. BBC News. 2 July 2017

1848:White, Matthew (2012).

399:, cited an estimate by

395:, in his 1977 article

388:Decapitated ball player

123:Legend of the Five Suns

121:culture. In the Aztec "

4308:Lienzo Antonio de León

3383:Sahagún, Bernardino de

2715:Díaz, Bernal (2005) .

2547:Bautista Pomar, Juan.

1605:"Fall of Tenochtitlan"

1506:

1455:Ecological explanation

1451:

1424:

1409:

1384:

1375:

1355:

1337:

1310:

1297:Itinerario de Grijalva

1274:Bartolomé de las Casas

1221:

796:, Tequitzin-Mayáhuel

740:Juan Bautista de Pomar

688:

673:

537:

475:

389:

366:

278:

155:

149:

23:

4468:Codex Totomixtlahuaca

4408:Relación de Michoacán

4358:Códice Maya de México

4343:Matrícula de Tributos

4268:Codex Fejérváry-Mayer

3713:Tlāhuizcalpantecuhtli

3355:. New Brunswick, NJ:

3251:León-Portilla, Miguel

2969:Winkelman, Michael. "

2448:Miller, Mary (1993).

2286:Bernardino de Sahagún

2234:History of the Indies

1750:By LiveScience Staff.

1545:Political explanation

1495:

1488:Religious explanation

1446:

1439:Proposed explanations

1419:

1404:

1379:

1366:

1350:

1333:isleta de Sacrificios

1328:

1305:

1215:

710:Calendar of sacrifice

683:

668:

527:

473:

449:in the Aztec capital

387:

355:

330:Mesoamerican ballgame

264:

239:Aztec Triple Alliance

164:Bernardino de Sahagún

151:

139:

21:

4498:Codex Zouche-Nuttall

4448:Anales de Tlatelolco

4338:Codex Magliabechiano

3588:(Four Tezcatlipocas)

3486:Arqueología Mexicana

3391:Arthur J.O. Anderson

2595:Sahagún, Bernadino.

2495:History of Religions

2094:Carnage and Culture,

2019:. pp. 141, 198.

1970:Arqueología Mexicana

1769:Smithsonian Magazine

1685:American Ethnologist

530:Codex Magliabechiano

171:Toribio de Benavente

142:Codex Magliabechiano

63:Maya human sacrifice

43:pre-Columbian Mexico

4388:Codex Porfirio Díaz

4383:Primeros Memoriales

4298:Codex Ixtlilxochitl

4293:Humboldt fragment 1

4283:Códice de Huichapan

4193:Badianus Manuscript

4147:The Stinking Corpse

3040:Marshall H. Saville

3036:Anonymous Conqueror

2861:(6395): 1288–1292.

2579:Primeros Memoriales

2531:Nahuatl dictionary.

2182:. pp. 111–124.

1642:1917GeogJ..49...61T

1469:Cannibals and Kings

1235:Telleriano-Remensis

413:Victor Davis Hanson

409:Codex Ixtlilxochitl

210:Holistic assessment

4353:Crónica Mexicayotl

4238:Codex Chimalpopoca

3827:Itzpapalotlcihuatl

3807:Huitztlampaehecatl

3668:Tezcatlipoca (see

3634:Lords of the Night

3480:Graulich, Michel.

3180:. Saint Paul, MN:

3062:– via FAMSI.

2799:Cartas de relación

1507:

1452:

1222:

1160:, Huitzilncuátec

1152:Tona-Cozcamiauh,

787:Tlacaxipehualiztli

699:Tlacaxipehualiztli

689:

666:, Sahagún wrote:

538:

476:

390:

367:

279:

150:

24:

4506:

4505:

4483:Codex Vaticanus B

4443:Tira de Tepechpan

4288:Codex Huexotzinco

4233:Codex Chimalpahin

4152:Use of entheogens

4119:Tlillan-Tlapallan

4013:Centzon Tōtōchtin

4008:Centzonhuītznāhua

3734:Acuecueyotl (see

3589:

3503:is a part of the

3456:978-0-8076-1278-1

3435:Mary Ellen Miller

3414:978-0-87480-082-1

3387:Charles E. Dibble

3366:978-0-8135-1562-5

3292:978-968-16-5712-3

3229:978-0-8061-2121-5

3191:978-1-55778-836-8

3160:978-0-8061-2649-4

3122:978-0-14-044123-9

3082:978-0-8070-4642-5

3003:, op. cit, p. 104

2417:(op. cit.), p. 83

2352:. pp. 83–93.

2292:(op. cit.), p. 76

1738:By Mark Stevenson

1241:, and Sahagún's

1205:

1204:

728:New Fire ceremony

615:New Fire Ceremony

445:found in 2015 at

129:, a body of the

4536:

4453:Codex Tlatelolco

4273:Codex Florentine

4213:Codex Borbonicus

4183:Codex Azcatitlan

4178:Aubin Tonalamatl

4109:Thirteen Heavens

3872:Mictlanpachecatl

3832:Itzpapalotltotec

3752:Chalchiuhtotolin

3693:Lords of the Day

3587:

3577:

3535:

3528:

3521:

3512:

3511:

3507:from around 1585

3497:

3468:

3447:George Braziller

3426:

3378:

3354:

3343:

3304:

3270:

3241:

3217:

3203:

3172:

3134:

3094:

3063:

3061:

3060:

3022:

3019:

3013:

3010:

3004:

3001:Historia general

2997:

2991:

2984:

2978:

2967:

2961:

2960:

2934:

2928:

2927:

2920:

2914:

2913:

2907:

2898:

2887:

2886:

2850:

2841:

2834:

2828:

2819:

2813:

2812:

2802:

2792:

2786:

2778:

2772:

2764:

2758:

2750:

2744:

2736:

2730:

2727:

2721:

2720:

2712:

2706:

2705:

2685:

2679:

2678:

2642:

2629:

2628:

2616:

2607:

2601:

2600:

2597:Florentine Codex

2592:

2583:

2582:

2574:

2568:

2567:

2559:

2553:

2552:

2544:

2538:

2528:

2519:

2518:

2490:

2484:

2481:

2475:

2472:

2466:

2459:

2453:

2446:

2440:

2433:

2427:

2426:Roy 2005, p. 316

2424:

2418:

2411:

2405:

2402:

2396:

2393:

2387:

2384:

2373:

2372:

2360:

2354:

2353:

2341:

2335:

2334:

2308:

2302:

2299:

2293:

2283:

2277:

2271:

2262:

2261:

2259:

2257:

2246:

2237:

2230:

2224:

2223:

2215:

2209:

2208:

2206:

2205:

2190:

2184:

2183:

2171:

2165:

2162:

2156:

2153:

2147:

2146:

2144:

2142:

2122:

2116:

2115:

2103:

2097:

2090:

2084:

2083:

2075:

2066:

2065:

2057:

2051:

2044:

2021:

2020:

2012:

2003:

2000:

1994:

1993:

1985:

1979:

1978:

1964:

1947:

1946:

1918:

1907:

1906:

1888:

1882:

1881:

1879:

1877:

1863:

1854:

1853:

1845:

1839:

1838:

1826:

1820:

1817:

1808:

1807:

1805:

1803:

1788:

1779:

1778:

1776:

1775:

1763:Gershon, Livia.

1760:

1751:

1745:

1739:

1733:

1727:

1726:

1718:

1712:

1711:

1701:

1675:

1662:

1661:

1625:

1619:

1618:

1617:

1616:

1601:

1550:tiered with the

1512:neteotoquiliztli

1504:

1393:Crown of Castile

1289:Juan de Grijalva

1266:Juan de Grijalva

749:

748:

427:Elizabeth Graham

423:Florentine Codex

265:A jaguar-shaped

253:Sacrifice ritual

189:Florentine Codex

99:Hueyi Tzompantli

39:Valley of Mexico

4544:

4543:

4539:

4538:

4537:

4535:

4534:

4533:

4529:Human sacrifice

4509:

4508:

4507:

4502:

4348:Codex Mexicanus

4278:Codex Huamantla

4253:Codex Cozcatzin

4243:Codex Colombino

4156:

4134:

4128:

4052:

4003:Centzonmīmixcōa

3986:

3837:Itztlacoliuhqui

3736:Chalchiuhtlicue

3659:Piltzintecuhtli

3644:Chalchiuhtlicue

3620:

3596:Huītzilōpōchtli

3586:

3578:

3569:

3544:

3542:Aztec mythology

3539:

3476:

3471:

3457:

3415:

3367:

3293:

3230:

3192:

3161:

3123:

3083:

3058:

3056:

3030:

3025:

3020:

3016:

3011:

3007:

2998:

2994:

2990:, p. 177 Note 4

2985:

2981:

2968:

2964:

2949:

2935:

2931:

2922:

2921:

2917:

2905:

2899:

2890:

2851:

2844:

2835:

2831:

2820:

2816:

2793:

2789:

2779:

2775:

2765:

2761:

2751:

2747:

2737:

2733:

2728:

2724:

2713:

2709:

2686:

2682:

2643:

2632:

2614:

2608:

2604:

2593:

2586:

2575:

2571:

2560:

2556:

2545:

2541:

2529:

2522:

2491:

2487:

2482:

2478:

2474:Sahagun Bk 2: 4

2473:

2469:

2460:

2456:

2447:

2443:

2434:

2430:

2425:

2421:

2412:

2408:

2403:

2399:

2394:

2390:

2385:

2376:

2361:

2357:

2342:

2338:

2323:

2309:

2305:

2300:

2296:

2284:

2280:

2272:

2265:

2255:

2253:

2248:

2247:

2240:

2231:

2227:

2216:

2212:

2203:

2201:

2191:

2187:

2172:

2168:

2163:

2159:

2155:Hanson, p. 195.

2154:

2150:

2140:

2138:

2131:Natural History

2123:

2119:

2104:

2100:

2091:

2087:

2076:

2069:

2058:

2054:

2045:

2024:

2013:

2006:

2001:

1997:

1986:

1982:

1965:

1950:

1919:

1910:

1903:

1889:

1885:

1875:

1873:

1865:

1864:

1857:

1846:

1842:

1827:

1823:

1818:

1811:

1801:

1799:

1789:

1782:

1773:

1771:

1761:

1754:

1746:

1742:

1734:

1730:

1719:

1715:

1676:

1665:

1650:10.2307/1779784

1626:

1622:

1614:

1612:

1603:

1602:

1598:

1594:

1572:

1547:

1498:tecpatlixquahua

1490:

1463:

1457:

1441:

1429:

1389:

1321:

1315:

1286:

1210:

1208:Primary sources

1113:Huitzilopochtli

1106:Panquetzaliztli

974:Mictlantecuhtli

966:Huitzilopochtli

912:Tecuilhuitontli

872:Huitzilopochtli

794:Huitzilopochtli

735:52-year cycle.

723:

718:

712:

678:

642:

636:

583:

522:

479:Huitzilopochtli

468:

466:Huitzilopochtli

463:

350:

255:

223:

217:

212:

115:

27:Human sacrifice

12:

11:

5:

4542:

4532:

4531:

4526:

4521:

4504:

4503:

4501:

4500:

4495:

4490:

4485:

4480:

4478:Anales de Tula

4475:

4470:

4465:

4460:

4455:

4450:

4445:

4440:

4435:

4430:

4425:

4420:

4415:

4410:

4405:

4400:

4395:

4393:Mapa Quinatzin

4390:

4385:

4380:

4375:

4370:

4365:

4360:

4355:

4350:

4345:

4340:

4335:

4330:

4325:

4320:

4315:

4310:

4305:

4300:

4295:

4290:

4285:

4280:

4275:

4270:

4265:

4260:

4255:

4250:

4245:

4240:

4235:

4230:

4225:

4223:Codex Boturini

4220:

4215:

4210:

4205:

4200:

4195:

4190:

4185:

4180:

4175:

4170:

4164:

4162:

4158:

4157:

4155:

4154:

4149:

4144:

4138:

4136:

4130:

4129:

4127:

4126:

4121:

4116:

4111:

4106:

4101:

4096:

4086:

4084:Huēyi Teōcalli

4081:

4076:

4071:

4066:

4060:

4058:

4054:

4053:

4051:

4050:

4045:

4040:

4035:

4030:

4025:

4020:

4015:

4010:

4005:

4000:

3994:

3992:

3988:

3987:

3985:

3984:

3979:

3974:

3969:

3964:

3959:

3954:

3949:

3944:

3939:

3934:

3929:

3924:

3919:

3914:

3909:

3904:

3899:

3894:

3889:

3884:

3879:

3874:

3869:

3864:

3859:

3857:Malinalxochitl

3854:

3849:

3844:

3839:

3834:

3829:

3824:

3819:

3814:

3809:

3804:

3799:

3794:

3789:

3784:

3779:

3774:

3769:

3764:

3759:

3754:

3749:

3744:

3739:

3732:

3727:

3726:

3725:

3720:

3715:

3710:

3705:

3703:Mictēcacihuātl

3700:

3690:

3689:

3688:

3683:

3678:

3673:

3666:

3661:

3656:

3654:Mictlāntēcutli

3651:

3646:

3641:

3630:

3628:

3622:

3621:

3619:

3618:

3608:

3603:

3598:

3592:

3590:

3580:

3579:

3572:

3570:

3568:

3567:

3560:Tōnacātēcuhtli

3552:

3550:

3546:

3545:

3538:

3537:

3530:

3523:

3515:

3509:

3508:

3498:

3496:on 2010-03-14.

3488:(in Spanish).

3475:

3474:External links

3472:

3470:

3469:

3455:

3427:

3413:

3379:

3365:

3344:

3318:(2): 403–406.

3305:

3291:

3271:

3243:

3242:

3228:

3204:

3190:

3173:

3159:

3135:

3121:

3095:

3081:

3071:. Boston, MA:

3064:

3031:

3029:

3026:

3024:

3023:

3014:

3005:

2992:

2979:

2962:

2947:

2929:

2915:

2888:

2842:

2829:

2814:

2787:

2773:

2759:

2745:

2731:

2722:

2707:

2696:(2): 257–295.

2680:

2653:(2): 403–406.

2630:

2602:

2584:

2569:

2554:

2539:

2520:

2507:10.1086/463405

2485:

2476:

2467:

2454:

2441:

2428:

2419:

2406:

2397:

2388:

2374:

2355:

2336:

2322:978-0226094878

2321:

2303:

2301:Sahagún, Ibid.

2294:

2278:

2263:

2238:

2225:

2210:

2185:

2166:

2157:

2148:

2117:

2098:

2085:

2067:

2064:. p. 159.

2060:Diaz, Bernal.

2052:

2022:

2004:

1995:

1980:

1948:

1929:(4): 415–432.

1908:

1901:

1883:

1855:

1840:

1837:. p. 402.

1821:

1809:

1797:Sciencemag.org

1791:Wade, Lizzie.

1780:

1752:

1740:

1728:

1713:

1692:(1): 117–135.

1663:

1620:

1595:

1593:

1590:

1589:

1588:

1583:

1578:

1576:Aztec religion

1571:

1568:

1546:

1543:

1489:

1486:

1459:Main article:

1456:

1453:

1449:British Museum

1440:

1437:

1428:

1425:

1388:

1385:

1317:Main article:

1314:

1311:

1285:

1282:

1239:Magliabechiano

1209:

1206:

1203:

1202:

1199:

1191:

1188:

1187:

1184:

1177:

1169:

1165: