483:, Argentina. They killed or captured hundreds of people, ransoming some captives and keeping others as slaves, and much livestock. Mbaya raids in Paraguay during the same decade resulted in the death of 500 Paraguayans and the theft of 6,000 head of livestock. However, Guaycuruan power had reached its zenith. A smallpox epidemic from 1732 to 1736 killed many, especially Mocobis; Spanish settlements were encroaching on the Chaco, and some of the Guaycuruans were adopting Spanish culture and religion. Moreover, the human pressure on the Chaco led to its environmental deterioration and it became less suitable as a habitat for the traditional hunting-gathering culture plus horse and cattle herds of the Chaco peoples.

497:, north of Santa Fe, Argentina in 1743. Several other missions were established among the various ethnic groups of the Guaycuru and the mission population reached a peak of 5,000 to 6,000 in the early 1780s. The population of the missions was unstable as many Guaycuruans returned to their nomadic ways after a residence at a mission. Many Guaycuruans were also, by this time, integrated into the Spanish economy, raising livestock, growing crops, and working for wages--although many also continued smuggling and stealing livestock and remained hostile to the Spanish.

30:

506:

376:

408:"These Indians are great warriors and valiant men, who live on venison, butter, honey, fish, and wild boar...They go daily to the chase for it is their only occupation. They are nimble and quick, so long-winded that they tire out the deer and catch them with their hands...They are kind to their wives...They are much feared by all the other tribes. They never remain more than two days in one place, but quickly remove their houses, made of matting..."

77:

63:

518:

parts of the Gran Chaco. In the independence movement of the 1810s and 1820s some

Guaycuruans served with the colonial independence armies, others resumed their raiding ways and expelled settlers from part of the Argentine Chaco. However, old animosities among the various ethnic groups making up the Guaycuruans led to internecine warfare among Tobas, Macobis, and Albipones. The Mbayas were increasingly absorbed into Brazilian society.

91:

49:

142:

529:

The still-nomadic Tobas and

Mocovis in the Argentine Chaco continued to resist the advancing frontier until 1884, when they were decisively defeated by the army; while a number of them agreed to thereafter live in reductions, thousands of Tobas retreated to isolated regions of Argentina, Paraguay and

462:

In 1542, Cabeza de Vaca responded to the request of the Guaraní to punish the hostile

Guaycuru. He dispatched a large expedition of Spaniard and Guaraní soldiers from Asunción and attacked an encampment of Mbayas, also called Eyiguayegis. The Spanish and Guaraní killed many and took 400 prisoners.

277:

The 16th century

Guaycuru appear to have been a southern band of the Mbaya rather than a separate people. The terms Mbaya and Guaycuru were synonymous to the early Spanish colonists. Guaycuru came to be the collective name applied to all the bands speaking similar languages, called Guaycuruan.

521:

Only a "small, depressed colony" of the once powerful Payaguá still survived near Asunción in 1852. The last known Payaguá, Maria

Dominga Miranda, died in the early 1940s. The Abipón became extinct in the last half of the 19th century. The Mbayas were given land by Brazil for their assistance in the

517:

By the early 19th century, when the South

American countries sought independence from Spain, the Guaycuruan peoples were divided among those who lived in missions and were at least partially integrated into Hispanic and Christian society and those who continued to live as nomads in the more isolated

424:

missions east of the

Paraguay and Parana rivers. Between raids they traded skins, wax, honey, salt, and Guaraní slaves to the Spanish en exchange for knives, hatchets, and other products. The mobility afforded by the horse facilitated Guaycuruan control over other peoples in the Chaco and made

428:

The Payaguá, inhabiting the shores of the

Paraguay River north of the city of Asunción, were an exception to the horse culture of other Guaycuruans. The Payagua plied the river in canoes, fished and gathered edible plants, and raided their agricultural neighbors, the Guaraní, to the east. The

453:

The

Guaycuruan population of the Chaco in pre-Hispanic times has been estimated to be as high as 500,000 people. Although documentation is mostly lacking, the Guaycuruans were impacted by epidemics of European diseases, but possibly less than their settled, agricultural neighbors such as the

399:

When first encountered in the 16th century, the

Guaycuru lived in the Gran Chaco, an inhospitable region for agriculture and settlement in the eyes of the Spanish colonists. They were hunter-gatherers and nomadic, moving from place to place as dictated by seasonal resources. The governor of

335:

and appear to form a linguistic and ethnic continuum. They have been placed together with the Abipón in the "Southern" division, while the Kadiweu are placed by themselves in a "Northern" division. The placement of the Payaguá in this classification is still controversial.

463:

In the aftermath of the battle, however, the Guaycuruans retained their control of the Chaco and gradually acquired horses, a taste for Spanish beef, and iron weapons and tools. In the 17th century, Guaycuruan raids forced the abandonment of

395:

The Guaycuru people consisted of many bands making up distinct ethnic groups with different but similar languages. The Guaycuruans were never politically united and were often hostile to each other as well as to other peoples.

258:, meaning "savage" or "barbarian", which later was extended to the whole group. It has also been used in the past to include other peoples of the Chaco region, but is now restricted to those speaking a Guaicuruan language.

475:

and other nearby Argentine provinces. Their raids forced the Spanish to abandon some frontier areas. Frequent Spanish military expeditions against the Guaycuruans were only temporarily successful if at all.

471:. In retaliation, in 1677, the Spanish massacred 300 Mbayan traders who were camped near Asunsción. By the early 1700s, bands of up to 400 Guaycuruan warriors were attacking Spanish settlements in

450:) pods which were used to produce a fermented alcoholic beverage. The reunions were used to designate leaders, reinforce relations among the bands, and facilitate courtships and marriages.

549:

In the 1968 census 16,548 Tobas and 1,202 of the closely related Pilagás were counted in Argentina. 2,600 Tobas were living in Bolivia. 3,000 to 6,000 Mocovis lived in Argentina in 1968.

615:, Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 3-5. Anthropologists have resisted calling the Guaycuruan ethnic groups "tribes" as no tribal government or distinct tribal territories existed.

542:, Argentina, but was quickly squelched when 500 of them were repulsed after an attack on the town. In 1924, Argentine police and military killed 400 Toba in what was called the

356:

367:

language family, but it is not clear yet whether the similarities between the vocabularies of the two families are due to a common origin or to borrowing.

429:

Payaguá also became great traders, both with the Spanish and other Guaycuruans. The Payaguá menaced Spanish travel on the Paraguay river for 200 years.

412:

The Abipón Guaycuruans acquired horses from the Spanish in the late 16th century and within 50 years developed a horse culture similar to that of the

344:

340:

790:

628:

New York: Verso, pp 49-50. It is unclear what Cabeza de Vaca meant by "butter" as the Guaycuru had no livestock in the 16th century.

805:

800:

261:

First encountered by the Spanish in the 16th century, the Guaycuru peoples strongly resisted Spanish control and the efforts of

810:

795:

531:

164:

401:

646:

Saegar, pp. 18-19. The Payaguá may also have given their name to the Paraguay River and the country of Paraguay.

493:

among the Guaycuruans in the early 1600s. Their first successful mission was established among the Mocobis at

364:

416:

of North America. They and other Guaycuruans acquired horses and cattle by raiding Spanish haciendas and

726:

Ganson, Barbara (2017), "The Evueví of Paraguay: Adaptive Strategies and Responses to Colonialism",

464:

686:

Seager, pp. 21-25. There are notable similarities between the defeats of the Guaycuruans and the

440:. The bands only united on ceremonial occasions, especially during the harvest period for wild

583:

539:

494:

433:

176:

109:

8:

468:

388:

241:

543:

472:

655:

Citro, Silvia (2009), "Los indigenas chaqueños en la mirada de los jesuitas germanos,"

360:

29:

479:

The Guaycuruans largest raid came in 1735 when 1,000 Mocobis and Tobas descended upon

753:

188:

454:

Guaraní, The Guaycuruan population in the mid 17th century is estimated at 40,000.

417:

322:

133:

510:

352:

348:

266:

219:

183:

explorers and colonists, the Guaycuru people lived in the present-day countries of

311:

296:

285:

150:

316:

251:

687:

602:, Smithsonian Institution, Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., p. 215

523:

480:

413:

384:

301:

262:

255:

180:

582:. Suplemento Antropológico, volume 41 issue 2, pp. 7–132. Asunción, Paraguay.

530:

Bolivia and retained some level of autonomy into the 20th century. In 1904, a

784:

505:

172:

380:

740:

535:

291:

626:

Land without Evil: Utopian Journeys across the South American Watershed,

526:(1864-1870), but survive only as the Kadiweu, numbering 1,400 in 2014..

307:

Other Guaycuru groups have become extinguished over the last 500 years:

490:

425:

raiding the Spaniards and their Indian allies a profitable enterprise.

375:

168:

200:

269:

them. They were not fully pacified until the early 20th century.

184:

82:

446:

192:

68:

489:

missionaries made unsuccessful attempts to establish missions or

437:

121:

96:

16:

Family of ethnic groups of the Gran Chaco, central South America

486:

421:

196:

54:

441:

432:

The bands and family groups making up the Guaycuruans were

34:

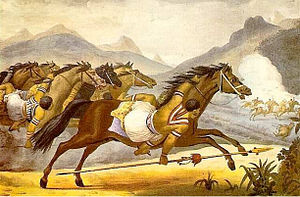

Debret's depiction of the Guaycuru cavalry during an attack

141:

730:, Vol 74, Issue 52, p. 463. Downloaded from Project Muse.

538:

in the North American West, erupted among the Mocovis of

250:). It was originally an offensive epithet given to the

179:. In the 16th century, the time of first contact with

613:

The Chaco Mission Frontier: The Guaycuruan Experience

754:https://pib.socioambiental.org/en/povo/kadiweu/260

782:

281:The major extant branches of the Guaycuru are:

379:The Guaycuru peoples lived mostly west of the

391:in Argentina northward to Brazil and Bolivia.

329:The Mocoví, Toba, and Pilagá call themselves

163:is a generic term for several ethnic groups

73:

404:, said in the 1540s of the Guaycuru :

59:

87:

580:Los pueblos del Gran Chaco y sus lenguas

504:

374:

140:

45:

741:https://www.britannica.com/topic/Abipon

570:

568:

566:

564:

562:

783:

756:, accessed 21 Nov 2017; Saegar, p. 178

752:"Kadiweu", Povos Indigenas no Brasil,

791:Indigenous peoples of the Gran Chaco

559:

40:Regions with significant populations

359:, have joined the Guaycuru and the

13:

596:Handbook of South American Indians

467:, Argentina and the relocation of

14:

822:

611:Saegar, James Schofield (2000),

594:Steward, Julian H., ed. (1946),

325:, also known as Evueví or Evebe.

89:

75:

61:

47:

28:

806:Indigenous peoples in Argentina

768:

759:

746:

733:

720:

711:

702:

693:

680:

801:Indigenous peoples in Paraguay

671:

662:

649:

640:

631:

618:

605:

588:

1:

811:Indigenous peoples in Bolivia

552:

796:Indigenous peoples in Brazil

272:

7:

10:

827:

585:, accessed on 15 Nov 2017.

500:

457:

402:Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca

370:

319:(ancestral to the Kadiweu)

254:people of Paraguay by the

148:

534:, similar to that of the

145:Guaycuru nomads by Debret

132:

127:

120:

115:

108:

103:

44:

39:

27:

149:Not to be confused with

743:, accessed 21 Nov 2017

624:Gott, Richard (1993),

514:

465:Concepción del Bermejo

410:

392:

339:Some authors, such as

146:

508:

406:

378:

144:

128:Related ethnic groups

574:Alain Fabre (2006),

540:San Javier, Santa Fe

532:millenarian movement

206:The name is written

177:Guaicuruan languages

110:Guaicuruan languages

774:Saegar, pp. 178-179

765:Saegar, pp. 176-177

708:Saegar, pp. 166-169

600:The Marginal Tribes

469:Santa Fe, Argentina

175:, speaking related

24:

515:

513:, Argentina, 1892.

393:

361:Mataguay languages

147:

22:

690:of North America.

659:, Vol 104, p. 399

189:Santa Fe Province

139:

138:

818:

775:

772:

766:

763:

757:

750:

744:

737:

731:

724:

718:

715:

709:

706:

700:

699:Saegar, p. 29-40

697:

691:

684:

678:

677:Saeger, pp. 5-13

675:

669:

666:

660:

653:

647:

644:

638:

635:

629:

622:

616:

609:

603:

592:

586:

572:

544:Napalpí massacre

511:Formosa Province

420:settlements and

265:missionaries to

99:

95:

93:

92:

85:

81:

79:

78:

71:

67:

65:

64:

57:

53:

51:

50:

32:

25:

21:

826:

825:

821:

820:

819:

817:

816:

815:

781:

780:

779:

778:

773:

769:

764:

760:

751:

747:

738:

734:

725:

721:

717:Gott, pp. 58-59

716:

712:

707:

703:

698:

694:

685:

681:

676:

672:

667:

663:

654:

650:

645:

641:

637:Saegar, pp. 5-9

636:

632:

623:

619:

610:

606:

593:

589:

573:

560:

555:

503:

460:

444:and algarroba (

385:Paraguay Rivers

373:

365:Mataco–Guaycuru

275:

195:, Bolivia, and

154:

151:Guaycura people

90:

88:

76:

74:

62:

60:

48:

46:

35:

20:

17:

12:

11:

5:

824:

814:

813:

808:

803:

798:

793:

777:

776:

767:

758:

745:

732:

719:

710:

701:

692:

688:Plains Indians

679:

670:

661:

648:

639:

630:

617:

604:

587:

557:

556:

554:

551:

524:Paraguayan War

502:

499:

481:Salta Province

459:

456:

414:Plains Indians

372:

369:

363:into a larger

327:

326:

320:

314:

305:

304:

299:

294:

289:

274:

271:

137:

136:

130:

129:

125:

124:

118:

117:

113:

112:

106:

105:

101:

100:

42:

41:

37:

36:

33:

18:

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

823:

812:

809:

807:

804:

802:

799:

797:

794:

792:

789:

788:

786:

771:

762:

755:

749:

742:

736:

729:

723:

714:

705:

696:

689:

683:

674:

665:

658:

652:

643:

634:

627:

621:

614:

608:

601:

597:

591:

584:

581:

577:

571:

569:

567:

565:

563:

558:

550:

547:

545:

541:

537:

533:

527:

525:

519:

512:

507:

498:

496:

492:

488:

484:

482:

477:

474:

470:

466:

455:

451:

449:

448:

443:

439:

435:

430:

426:

423:

419:

415:

409:

405:

403:

397:

390:

386:

382:

377:

368:

366:

362:

358:

357:Viegas Barros

354:

350:

346:

342:

337:

334:

333:

324:

321:

318:

315:

313:

310:

309:

308:

303:

300:

298:

295:

293:

290:

287:

284:

283:

282:

279:

270:

268:

264:

259:

257:

253:

249:

248:

243:

239:

238:

233:

232:

227:

226:

221:

217:

216:

211:

210:

204:

202:

198:

194:

190:

186:

182:

178:

174:

173:South America

170:

166:

162:

158:

152:

143:

135:

131:

126:

123:

119:

114:

111:

107:

102:

98:

84:

70:

56:

43:

38:

31:

26:

770:

761:

748:

735:

728:The Americas

727:

722:

713:

704:

695:

682:

673:

668:Saeger, p. 6

664:

656:

651:

642:

633:

625:

620:

612:

607:

599:

595:

590:

579:

578:, Part 3 of

576:Los guaykurú

575:

548:

528:

520:

516:

485:

478:

461:

452:

445:

431:

427:

411:

407:

398:

394:

338:

331:

330:

328:

306:

280:

276:

267:Christianize

260:

246:

245:

236:

235:

230:

229:

224:

223:

214:

213:

208:

207:

205:

160:

156:

155:

19:Ethnic group

536:Ghost Dance

785:Categories

739:"Abipón",

598:, Vol. 1,

553:References

495:San Javier

491:reductions

434:matrilocal

400:Paraguay,

242:Portuguese

231:guaicurúes

225:guaycurúes

199:(south of

187:(north of

171:region of

169:Gran Chaco

165:indigenous

657:Anthropos

509:Tobas in

438:exogamous

353:Greenberg

273:Divisions

247:guaicurus

185:Argentina

104:Languages

83:Argentina

447:Prosopis

389:Santa Fe

288:(Mocobi)

263:Catholic

244:(plural

237:guaicuru

222:(plural

215:guaicurú

209:guaycurú

193:Paraguay

161:Guaykuru

157:Guaycuru

116:Religion

69:Paraguay

23:Guaycuru

501:Decline

473:Tucuman

458:History

418:Guaraní

371:Culture

341:Quevedo

323:Payaguá

302:Kadiweu

256:Guarani

234:), and

220:Spanish

201:Corumbá

181:Spanish

167:to the

134:Guarani

122:Animism

97:Uruguay

487:Jesuit

422:Jesuit

381:Parana

312:Abipón

297:Pilagá

286:Mocoví

197:Brazil

94:

80:

66:

55:Brazil

52:

442:honey

387:from

349:Mason

317:Mbayá

252:Mbayá

546:.

436:and

383:and

355:and

345:Hunt

292:Toba

332:qom

240:in

228:or

218:in

212:or

203:).

191:),

159:or

787::

561:^

351:,

347:,

343:,

153:.

86:,

72:,

58:,

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.