20:

71:– that whatever one clearly and distinctly perceives is true: "I now seem to be able to lay it down as a general rule that whatever I perceive very clearly and distinctly is true" (AT VII 35). He goes on in the same Meditation to argue for the existence of a benevolent God, in order to defeat his skeptical argument in the first Meditation that God might be a deceiver. He then says that without his knowledge of God's existence, none of his knowledge could be certain.

199:. Frankfurt suggests that Descartes's arguments for the existence of God, and for the reliability of reason, are not intended to prove that their conclusions are true, but to show that reason leads to them. Thus, reason is validated by being shown to confirm its own validity instead of leading to a denial of its validity by being shown to be incapable of demonstrating the existence of a benevolent God.

124:

Descartes' own response to this criticism, in his "Author's

Replies to the Fourth Set of Objections", is first to give what has become known as the Memory response; he points out that in the fifth Meditation (at AT VII 69–70) he did not say that he needed God to guarantee the truth of his clear and

159:

presents the memory defense as follows: "When one is actually intuiting a given proposition, no doubt can be entertained. So any doubt there can be must be entertained when one is not intuiting the proposition." He goes on to argue: "The trouble with

Descartes's system is not that it is circular;

113:

You are not yet certain of the existence of God, and you say that you are not certain of anything. It follows from this that you do not yet clearly and distinctly know that you are a thinking thing, since, on your own admission, that knowledge depends on the clear knowledge of an existing God; and

129:

When I said that we can know nothing for certain until we are aware that God exists, I expressly declared that I was speaking only of knowledge of those conclusions which can be recalled when we are no longer attending to the arguments by means of which we deduced them. (AT VII

160:

nor that there is an illegitimate relation between the proofs of God and the clear and distinct perceptions The trouble is that the proofs of God are invalid and do not convince even when they are supposedly being intuited."

144:, but recognizes it as something self-evident by a simple intuition of the mind" (AT VII 140). Finally, he points out that the certainty of clear and distinct ideas does not depend upon God's guarantee (AT VII 145–146). The

121:

was another one of

Descartes' objectors, likewise arguing that God's existence cannot be used to prove that what one clearly and distinctly perceives is true.

164:

140:

is an inference: "When someone says 'I am thinking, therefore I am, or I exist' he does not deduce existence from thought by means of a

402:

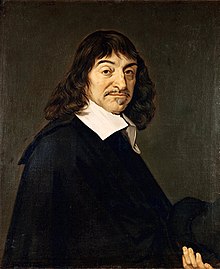

385:

Carriero, John (2008). "The

Cartesian Circle and the Foundations of Knowledge". In Broughton, Janet; Carriero, John (eds.).

78:

Descartes' proof of the reliability of clear and distinct perceptions takes as a premise God's existence as a non-deceiver.

114:

this you have not proved in the passage where you draw the conclusion that you clearly know what you are. (AT VII 124–125)

489:

375:

508:

370:. Vol. 2. Translated by John Cottingham; Robert Stoothoff; Dugald Murdoch. Cambridge University Press. 1984.

67:

287:

465:

513:

413:

187:

true and certain, that is, time-bound, and objectively possible (and does not need the guarantee of God).

85:

Many commentators, both at the time that

Descartes wrote and since, have argued that this involves a

81:

Descartes' proofs of God's existence presuppose the reliability of clear and distinct perceptions.

19:

213:

8:

433:

208:

42:

518:

485:

437:

398:

371:

86:

46:

477:

425:

390:

156:

90:

192:

136:

118:

33:

394:

191:

Another defense of

Descartes against the charge of circularity is developed by

102:

89:, as he relies upon the principle of clarity and distinctness to argue for the

39:

502:

447:

Demons, Dreamers, and Madmen: the

Defense of Reason in Descartes' Meditations

148:

in particular is self-verifying, indubitable, immune to the strongest doubt.

93:, and then claims that God is the guarantor of his clear and distinct ideas.

455:

Hatfield, Gary (2006). "The

Cartesian Circle". In Gaukroger, Stephen (ed.).

252:

429:

74:

The

Cartesian circle is a criticism of the above that takes this form:

54:

295:

141:

183:

true and certain (with the guarantee of God), while the former is

179:; both are true and cannot be contradicted, but the latter is

50:

414:"Descartes' Dualism: Correcting Some Misconceptions"

65:

Descartes argues – for example, in the third of his

171:The distinction appropriate here is that between

500:

16:Error in reasoning attributed to René Descartes

451:Reprinted by Princeton University Press, 2007.

389:. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 302–318.

125:distinct ideas, only to guarantee his memory:

457:The Blackwell Guide to Descartes' Meditations

101:The first person to raise this criticism was

411:

339:

96:

105:, in the "Second Set of Objections" to the

232:

444:

351:

134:Secondly, he explicitly denies that the

476:

454:

384:

327:

315:

275:

18:

470:The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

368:The Philosophical Writings of Descartes

501:

482:Descartes: The Project of Pure Enquiry

463:

264:

237:. Oxford University Press. p. 49.

151:

57:, which is itself guaranteed by God.

418:Journal of the History of Philosophy

412:Christofidou, Andrea (April 2001).

13:

49:. He argued that the existence of

14:

530:

269:

45:attributed to French philosopher

68:Meditations on First Philosophy

60:

345:

333:

321:

309:

280:

258:

241:

226:

1:

360:

468:. In Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

197:Demons, Dreamers, and Madmen

7:

464:Newman, Lex (Spring 2019).

202:

10:

535:

395:10.1002/9780470696439.ch18

251:, ed. by Charles Adam and

466:"Descartes' Epistemology"

445:Frankfurt, Harry (1970).

233:Cottingham, John (1988).

97:Descartes' contemporaries

387:A Companion to Descartes

219:

509:Philosophical arguments

288:"The Cartesian Circle"

189:

132:

116:

53:is proven by reliable

24:

430:10.1353/hph.2003.0098

169:

127:

111:

22:

249:Oeuvres de Descartes

214:Ontological argument

459:. pp. 122–141.

165:Andrea Christofidou

152:Modern commentators

38:) is an example of

514:Informal fallacies

342:, pp. 219–220

209:Circular reasoning

43:circular reasoning

25:

484:. Penguin Books.

478:Williams, Bernard

404:978-0-470-69643-9

340:Christofidou 2001

87:circular argument

526:

495:

473:

460:

450:

449:. Bobbs–Merrill.

441:

408:

381:

354:

349:

343:

337:

331:

325:

319:

313:

307:

306:

304:

303:

294:. Archived from

284:

278:

273:

267:

262:

256:

245:

239:

238:

235:The Rationalists

230:

157:Bernard Williams

91:existence of God

29:Cartesian circle

534:

533:

529:

528:

527:

525:

524:

523:

499:

498:

492:

405:

378:

366:

363:

358:

357:

350:

346:

338:

334:

326:

322:

314:

310:

301:

299:

286:

285:

281:

274:

270:

263:

259:

247:"AT" refers to

246:

242:

231:

227:

222:

205:

193:Harry Frankfurt

154:

119:Antoine Arnauld

99:

63:

31:(also known as

17:

12:

11:

5:

532:

522:

521:

516:

511:

497:

496:

490:

474:

461:

452:

442:

424:(2): 215–238.

409:

403:

382:

376:

362:

359:

356:

355:

352:Frankfurt 1970

344:

332:

320:

308:

292:www.owl232.net

279:

268:

257:

240:

224:

223:

221:

218:

217:

216:

211:

204:

201:

153:

150:

103:Marin Mersenne

98:

95:

83:

82:

79:

62:

59:

47:René Descartes

23:René Descartes

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

531:

520:

517:

515:

512:

510:

507:

506:

504:

493:

491:0-14-022006-2

487:

483:

479:

475:

471:

467:

462:

458:

453:

448:

443:

439:

435:

431:

427:

423:

419:

415:

410:

406:

400:

396:

392:

388:

383:

379:

377:0-521-28808-8

373:

369:

365:

364:

353:

348:

341:

336:

330:, p. 210

329:

328:Williams 1978

324:

318:, p. 206

317:

316:Williams 1978

312:

298:on 2017-10-08

297:

293:

289:

283:

277:

276:Carriero 2008

272:

266:

261:

254:

250:

244:

236:

229:

225:

215:

212:

210:

207:

206:

200:

198:

194:

188:

186:

182:

178:

174:

168:

166:

161:

158:

149:

147:

143:

139:

138:

131:

126:

122:

120:

115:

110:

108:

104:

94:

92:

88:

80:

77:

76:

75:

72:

70:

69:

58:

56:

52:

48:

44:

41:

37:

35:

30:

21:

481:

469:

456:

446:

421:

417:

386:

367:

347:

335:

323:

311:

300:. Retrieved

296:the original

291:

282:

271:

260:

253:Paul Tannery

248:

243:

234:

228:

196:

195:in his book

190:

185:subjectively

184:

180:

176:

172:

170:

162:

155:

145:

135:

133:

128:

123:

117:

112:

106:

100:

84:

73:

66:

64:

61:The argument

32:

28:

26:

265:Newman 2019

181:objectively

107:Meditations

503:Categories

361:References

302:2017-10-09

167:explains:

55:perception

40:fallacious

438:143664433

142:syllogism

36:'s circle

519:Ontology

480:(1978).

203:See also

177:scientia

173:cognitio

34:Arnauld

488:

436:

401:

374:

146:cogito

137:cogito

434:S2CID

220:Notes

486:ISBN

399:ISBN

372:ISBN

175:and

130:140)

27:The

426:doi

391:doi

163:As

51:God

505::

432:.

422:39

420:.

416:.

397:.

290:.

109::

494:.

472:.

440:.

428::

407:.

393::

380:.

305:.

255:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.