255:

that artists could create. Another perspective points to evidence such as the fact that "race records were distinguished by numerical series… in effect, segregated lists", to support the claim that white-owned companies aimed to maintain the racial divisions in society through race records. Media companies even implemented racial stereotypes in advertising to invoke black sentiments and sell more records. Others regard the investments as being motivated simply by profit, namely by the low cost of production resulting from the easy exploitation of black writers and musicians, combined with the ease of distribution to a highly targeted class of consumers who have little access to a fully competitive marketplace.

275:

an economic ideal for

African Americans to strive towards, proving that they could overcome social barriers and be successful. Hence, Black Swan paid fair wages and allowed artists to showcase their race records using their real names. Pace urged record companies owned by white individuals to recognize the demands of African Americans and increase the flow of race records in the future. Black Swan was eventually purchased by Paramount Records in 1924.

31:

163:, a black artist who did not fit the mold of popular white music. In 1920, Smith created her "Crazy Blues"/"It's Right Here for You" recording, which sold 75,000 copies to a majority-black audience in the first month. Okeh did not anticipate these sales and attempted to recreate their success by recruiting more black blues singers. Other big companies sought to profit from this new trend of race records.

271:. Black Swan was formed to integrate the black community into a primarily white music industry, issuing around five hundred race records per year. The creation of this company brought widespread support for race records from the African American community. However some white companies in the music industry were strongly against Black Swan and threatened the company on multiple occasions.

340:

Race' was a common term then, a self-referral used by blacks...On the other hand, 'Race

Records' didn't sit well...I came up with a handle I thought suited the music well – 'rhythm and blues.'... a label more appropriate to more enlightened times." The chart has since undergone further name changes,

274:

Pace not only issued jazz, blues, and gospel records, but he put out race records that deviated from popular

African American categories. These genres included classical, opera, and spirituals, chosen by Pace to encourage the advancement of African American culture. He intended the company to provide

286:

destroyed the race record market, leaving most

African American musicians jobless. Almost every major music company removed race records from their catalogs as the country turned to the radio. Black listenership for the radio consistently stayed below ten percent of the total black population during

254:

Perspectives on the reason white record companies invested in marketing race records vary, with some claiming it was "for the purpose of exploiting markets and expanding the capital of producers." Advocates of this philosophy emphasize the control that the companies had on the type and form of songs

250:

Companies like Okeh and

Paramount enforced their objectives in the 1920s by sending field scouts to Southern states to record black artists in a one-time deal. Scouts neglected the aspirations of many singers to continue working with their companies. Field recordings were presented to the public as

136:

in 1901, followed by black artists employed by other companies. Yet, the

African American artists that major record companies hired before the 1920s were not properly compensated or acknowledged. This was because contracts were given to black artists on the basis of a single record, so their future

247:. They carefully implemented words and images that would draw in their targeted audience. Race records ads frequently reminded readers of their shared experience, claiming the music could help African Americans who moved to the North stay connected with their Southern roots.

797:

based on sales reports from

Rainbow Music Shop, Harvard Radio Shop, Lehman Music Company, Harlem De Luxe Music Store, Ray's Music Shop and Frank's Melody Music Shop, New York." Andy Kirk and His Clouds of Joy topped the inaugural tally with "Take It and

108:

prevented most

African Americans from listening to recorded music. At the turn of the twentieth century, the cost of listening to music went down, providing a majority of Americans with the ability to afford records. The primary purpose of

302:

It has been noted that "whole areas of black vocal tradition have been overlooked, or at best have received a few tangential references." Though not studied comprehensively, race records have been preserved. Publications like

324:

published a Race

Records chart between 1945 and 1949, initially covering juke box plays and from 1948 also covering sales. This was a revised version of the Harlem Hit Parade chart, which it had introduced in 1942.

76:. These records were, at the time, the majority of commercial recordings of African American artists in the U.S., and few African American artists were marketed to white audiences. Race records were marketed by

120:

Mainstream records during the 1890s and the first two decades of the 1900s were mainly made by and targeted towards white, middle class, and urban

Americans. There were some exceptions, including

243:

brought competition to the record industry. To maximize exposure, record labels advertised in catalogs, brochures, and newspapers popular among African Americans, like the

167:

was the first to follow Okeh into the race records industry in 1921, while Paramount Records began selling race records in 1922 and Vocalion entered in the mid-1920s.

113:

was to spur on the sale of phonographs, which were most commonly distributed in furniture stores. The stores white and black people shopped at were separate due to

372:

965:. Music of the African Diaspora, 7. Berkeley and London: University of California Press; Chicago, Illinois: Center for Black Music Research, Columbia College.

175:

The term "race records" was coined in 1922 by Okeh Records. Such records were labeled "race records" in reference to their marketing to African Americans, but

287:

this time, as the music they enjoyed did not get airtime. The exclusion of black artists on the radio was further cemented when commercial networks like

224:. It listed the “most popular records in Harlem" and began to replace the term "race music" in the industry. The Harlem concept was replaced by R&B

573:

Roy, William (2004). ""Race Records" and "Hillbilly Music": Institutional Origins of Racial Categories in the American Commercial Recording Industry".

151:, a famous black composer, sparked a transition that displayed the potential for African American artists. Bradford persuaded the white executive of

221:

220:

began publishing charts of hit songs in 1940. Two years later, the company's list of songs popular among African Americans was created:

529:

Suisman, David (2004). "Co-Workers in the Kingdom of Culture: Black Swan Records and the Political Economy of African American Music".

114:

469:

443:

622:

Barretta, Paul (2017). "Tracing the Color Line in the American Music Market and Its Effect on Contemporary Music Marketing".

283:

193:

as "Our Race Artist". Most of the major recording companies issued "race" series of records from the mid-1920s to the 1940s.

906:"'race music' and 'race records' were terms used to categorize practically all types of African-American music in the 1940s"

780:

124:, a whistler who is widely believed to be the first black artist ever to record commercially, in 1890. Broadway stars

970:

931:

824:

212:

to refer to an African-American individual who showed pride in and support for African-American people and culture.

418:

133:

89:

200:

may seem derogatory; in the early 20th century, however, the African-American press routinely used the term

17:

1046:

299:

that rhythm and blues, a term spanning most sub-genres of race records, gained prevalence on the radio.

147:

consumed in the 1800s. Still, there were not any primarily black genres of music sold in early records.

186:

129:

121:

905:

1007:

724:

360:

225:

140:

1041:

841:

992:

350:

1015:

1056:

945:

365:

336:, the magazine changed the name of the chart to Rhythm & Blues Records. Wexler wrote, "

320:

216:

311:

list the names of race records that were commercially recorded and recorded in the field.

8:

755:

1023:

886:

669:

546:

304:

264:

156:

814:

179:

gradually began to purchase such records as well. In the 16 October 1920 issue of the

966:

927:

890:

869:

Dolan, Mark (2007). "Extra! Chicago Defender Race Records Ads Show South from Afar".

820:

473:

369:

R&B record chart, known as the Race Records chart from February 1945 to June 1949

110:

93:

49:

45:

447:

878:

661:

631:

582:

538:

408:

Oliver, Paul. "Race record". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 13 Feb. 2015.

181:

164:

85:

69:

27:

78-rpm phonograph records marketed to African Americans between the 1920s and 1940s

586:

144:

81:

1051:

355:

240:

176:

148:

1035:

810:

635:

125:

239:

Marketing race records was especially important in the late 1920s, when the

333:

296:

295:

started to hire white singers to cover black music. It was not until after

152:

77:

65:

882:

341:

becoming the Soul chart in August 1969, and the Black chart in June 1982.

251:

chance encounters to seem more genuine, yet they typically were arranged.

263:

The control of white owned music companies was tested in the 1920s, when

190:

160:

673:

550:

268:

105:

53:

30:

495:

378:

34:

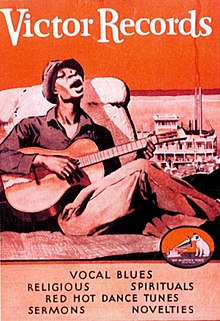

The cover of race records catalogue of Victor Talking Machine Company

665:

652:

Barlow, William (1995). "Black Music on Radio during the Jazz Age".

542:

117:, and the type of music available to white and black people varied.

496:"Watch Jazz | A Film by Ken Burns | PBS | Ken Burns"

231:

The term "rhythm and blues" fully replaced the term "race music".

781:"Weekly Chart Notes: Baauer Continues The 'Harlem' Hit Parade'"

104:

Before the rise of the record industry in America, the cost of

73:

42:

57:

61:

292:

288:

373:

List of number-one rhythm and blues hits (United States)

267:

was founded in 1921 by the African American businessman

712:. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 8–13.

56:, comprising various African-American musical genres,

52:

between the 1920s and 1940s. They primarily contained

1026:

Black and White: Crossing the Border, Closing the Gap

903:

694:. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 160.

314:

1033:

963:Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop

803:

189:, an advertisement for Okeh Records identified

924:Rhythm and the Blues: A Life in American Music

995:Mamie Smith and the Birth of the Blues Market

204:to refer to African Americans as a whole and

143:greatly influenced the popular media that

722:

809:

621:

29:

1008:St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture,

976:

946:"Black Music Charts: What's in a Name?"

833:

528:

14:

1034:

981:. University Microfilms International.

943:

839:

816:Top R&B/Hip-Hop Singles: 1942–1995

707:

689:

651:

604:. Chicago: U of Illinois P. p. 5.

599:

910:St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture

868:

864:

862:

743:The Oxford Companion to Popular Music

729:St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture

703:

701:

685:

683:

647:

645:

258:

617:

615:

613:

611:

568:

566:

564:

562:

560:

524:

522:

520:

518:

516:

404:

402:

400:

398:

396:

394:

922:Wexler, Jerry; Ritz, David (1993).

842:"The Real History of Rock and Roll"

572:

328:In June 1949, at the suggestion of

137:opportunities were not guaranteed.

24:

859:

698:

680:

642:

309:Blues and Gospel Records 1902-1943

25:

1068:

1001:

840:Menand, Louis (9 November 2015).

608:

557:

513:

391:

961:Ramsey, Guthrie P., Jr. (2003).

944:George, Nelson (June 26, 1982).

819:. Record Research. p. xii.

977:Foreman, Ronald C. Jr. (1969).

937:

916:

897:

773:

748:

735:

716:

531:The Journal of American History

96:, and several other companies.

979:Jazz and Race Records, 1920–32

904:Killmeier, Matthew A. (2002).

723:Killmeier, Matthew A. (2002).

593:

488:

462:

436:

411:

315:Transition to rhythm and blues

170:

134:Victor Talking Machine Company

90:Victor Talking Machine Company

13:

1:

926:. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

384:

986:

587:10.1016/j.poetic.2004.06.001

234:

7:

344:

10:

1073:

278:

187:African-American newspaper

99:

756:"Race Music: Chapter One"

361:Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs

636:10.1108/AAM-08-2016-0016

141:African-American culture

741:Gammond, Peter (1991).

654:African American Review

363:, for a history of the

196:In hindsight, the term

692:Seems Like Murder Here

375:(Billboard, 1942–1959)

351:African American music

35:

883:10.1353/scu.2007.0027

708:Oliver, Paul (1984).

690:Cussow, Adam (2002).

33:

710:Songsters and Saints

600:Brooks, Tim (2004).

284:The Great Depression

787:. February 22, 2013

624:Arts and the Market

1047:Gospel music media

476:on 8 February 2007

450:on 12 October 2008

265:Black Swan Records

259:Black Swan Records

46:phonograph records

36:

871:Southern Cultures

222:Harlem Hit Parade

122:George W. Johnson

94:Paramount Records

50:African Americans

16:(Redirected from

1064:

982:

954:

953:

941:

935:

920:

914:

913:

901:

895:

894:

866:

857:

856:

854:

852:

837:

831:

830:

807:

801:

800:

794:

792:

777:

771:

770:

768:

766:

752:

746:

739:

733:

732:

720:

714:

713:

705:

696:

695:

687:

678:

677:

649:

640:

639:

619:

606:

605:

597:

591:

590:

581:(3–4): 265–279.

570:

555:

554:

537:(4): 1295–1324.

526:

511:

510:

508:

506:

492:

486:

485:

483:

481:

472:. Archived from

466:

460:

459:

457:

455:

446:. Archived from

440:

434:

433:

431:

429:

415:

409:

406:

339:

245:Chicago Defender

182:Chicago Defender

165:Columbia Records

86:Vocalion Records

70:rhythm and blues

21:

1072:

1071:

1067:

1066:

1065:

1063:

1062:

1061:

1032:

1031:

1004:

989:

958:

957:

942:

938:

921:

917:

902:

898:

867:

860:

850:

848:

838:

834:

827:

808:

804:

790:

788:

779:

778:

774:

764:

762:

754:

753:

749:

740:

736:

721:

717:

706:

699:

688:

681:

666:10.2307/3042311

650:

643:

620:

609:

598:

594:

571:

558:

543:10.2307/3660349

527:

514:

504:

502:

494:

493:

489:

479:

477:

468:

467:

463:

453:

451:

442:

441:

437:

427:

425:

417:

416:

412:

407:

392:

387:

347:

337:

317:

281:

261:

237:

177:white Americans

173:

145:white Americans

102:

82:Emerson Records

28:

23:

22:

15:

12:

11:

5:

1070:

1060:

1059:

1054:

1049:

1044:

1042:Recorded music

1030:

1029:

1021:

1013:

1003:

1002:External links

1000:

999:

998:

988:

985:

984:

983:

974:

956:

955:

936:

915:

896:

877:(3): 107–110.

858:

846:The New Yorker

832:

825:

811:Whitburn, Joel

802:

772:

747:

734:

715:

697:

679:

660:(2): 325–328.

641:

607:

592:

556:

512:

487:

461:

435:

410:

389:

388:

386:

383:

382:

381:

376:

370:

358:

356:Cover versions

353:

346:

343:

316:

313:

307:and Godrich's

280:

277:

260:

257:

236:

233:

228:in June 1949.

226:chart listings

172:

169:

149:Perry Bradford

101:

98:

41:is a term for

26:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1069:

1058:

1055:

1053:

1050:

1048:

1045:

1043:

1040:

1039:

1037:

1028:

1027:

1022:

1020:

1019:

1014:

1012:

1011:

1006:

1005:

997:

996:

991:

990:

980:

975:

972:

971:0-520-21048-4

968:

964:

960:

959:

952:. p. 10.

951:

947:

940:

933:

932:0-224-03963-6

929:

925:

919:

911:

907:

900:

892:

888:

884:

880:

876:

872:

865:

863:

847:

843:

836:

828:

826:0-89820-115-2

822:

818:

817:

812:

806:

799:

786:

782:

776:

761:

757:

751:

744:

738:

730:

726:

719:

711:

704:

702:

693:

686:

684:

675:

671:

667:

663:

659:

655:

648:

646:

637:

633:

629:

625:

618:

616:

614:

612:

603:

596:

588:

584:

580:

576:

569:

567:

565:

563:

561:

552:

548:

544:

540:

536:

532:

525:

523:

521:

519:

517:

501:

497:

491:

475:

471:

465:

449:

445:

439:

424:

420:

414:

405:

403:

401:

399:

397:

395:

390:

380:

377:

374:

371:

368:

367:

362:

359:

357:

354:

352:

349:

348:

342:

335:

331:

326:

323:

322:

312:

310:

306:

300:

298:

294:

290:

285:

276:

272:

270:

266:

256:

252:

248:

246:

242:

232:

229:

227:

223:

219:

218:

213:

211:

207:

203:

199:

194:

192:

188:

184:

183:

178:

168:

166:

162:

158:

154:

150:

146:

142:

138:

135:

132:recorded for

131:

130:George Walker

127:

126:Bert Williams

123:

118:

116:

112:

107:

97:

95:

91:

87:

83:

79:

75:

71:

67:

63:

59:

55:

51:

47:

44:

40:

32:

19:

1057:Jazz culture

1025:

1018:Race records

1017:

1009:

994:

978:

962:

949:

939:

923:

918:

909:

899:

874:

870:

849:. Retrieved

845:

835:

815:

805:

796:

791:September 4,

789:. Retrieved

784:

775:

763:. Retrieved

759:

750:

742:

737:

728:

725:"Race Music"

718:

709:

691:

657:

653:

627:

623:

601:

595:

578:

574:

534:

530:

503:. Retrieved

499:

490:

478:. Retrieved

474:the original

464:

452:. Retrieved

448:the original

438:

426:. Retrieved

422:

413:

364:

334:Jerry Wexler

329:

327:

319:

318:

308:

301:

297:World War II

282:

273:

262:

253:

249:

244:

238:

230:

215:

214:

209:

205:

201:

197:

195:

180:

174:

159:, to record

153:Okeh Records

139:

119:

103:

78:Okeh Records

66:gospel music

48:marketed to

39:Race records

38:

37:

18:Race records

851:23 February

760:Ucpress.edu

602:Lost Sounds

423:Indiana.edu

332:journalist

198:race record

191:Mamie Smith

171:Terminology

161:Mamie Smith

115:segregation

106:phonographs

1036:Categories

1010:Race music

630:(2): 217.

385:References

269:Harry Pace

210:race woman

157:Fred Hager

54:race music

987:Listening

950:Billboard

891:144836496

785:Billboard

745:. p. 477.

379:Race film

366:Billboard

330:Billboard

321:Billboard

235:Marketing

217:Billboard

72:and also

813:(1996).

345:See also

206:race man

202:the Race

674:3042311

575:Poetics

551:3660349

500:Pbs.org

470:"Photo"

444:"Photo"

419:"Photo"

279:Decline

111:records

100:History

969:

930:

889:

823:

765:8 June

672:

549:

505:8 June

480:8 June

454:8 June

428:8 June

74:comedy

64:, and

43:78-rpm

1052:Blues

1024:NPR,

1016:PBS,

993:NPR,

887:S2CID

798:Git."

670:JSTOR

547:JSTOR

338:'

305:Dixon

241:radio

185:, an

58:blues

967:ISBN

928:ISBN

853:2021

821:ISBN

793:2023

767:2021

507:2021

482:2021

456:2021

430:2021

291:and

128:and

62:jazz

879:doi

662:doi

632:doi

583:doi

539:doi

293:CBS

289:NBC

208:or

1038::

948:.

908:.

885:.

875:13

873:.

861:^

844:.

795:.

783:.

758:.

727:.

700:^

682:^

668:.

658:29

656:.

644:^

626:.

610:^

579:32

577:.

559:^

545:.

535:90

533:.

515:^

498:.

421:.

393:^

155:,

92:,

88:,

84:,

80:,

68:,

60:,

973:.

934:.

912:.

893:.

881::

855:.

829:.

769:.

731:.

676:.

664::

638:.

634::

628:7

589:.

585::

553:.

541::

509:.

484:.

458:.

432:.

20:)

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.