338:

199:

346:

forced her to drink the cup too, so they both died. According to

Wolfram, there may be some historical truth in the account of Longinus' proposal to Rosamund, as it was possible to achieve Lombard kingship by marrying the queen, but the story of the two lovers' end is not historical but legendary. The mutual murder as told by Agnellus is given a different interpretation by Joaquin Martinez Pizarro: he sees Helmichis' last action as a symbol of how the natural hierarchy of sexes is at last restored, after the queen's actions had unnaturally modified the proper equilibrium.

128:

265:"Helmegis then, upon the death of his king, attempted to usurp his kingdom, but he could not at all do this, because the Langobards, grieving greatly for the king's death, strove to make way with him. And straightway Rosemund sent word to Longinus, prefect of Ravenna, that he should quickly send a ship to fetch them. Longinus, delighted by such a message, speedily sent a ship in which Helmegis with Rosemund his wife embarked, fleeing at night."

490:, a history of the Lombard nation up to 744. The book was finished in the last two decades of the 8th century, after the Lombard Kingdom had been conquered by the Franks in 774. Because of the apparent presence in the work of many fragments preserved from Lombard oral tradition, Paul's work has been often interpreted as a tribute to a vanishing culture. Among these otherwise lost traditions stands the tale of Alboin's death. According to

85:, which made him vulnerable to the ambitions of other prominent Lombards, such as Helmichis, who was Alboin's foster-brother and arms-bearer. After Alboin's death, Helmichis attempted to gain the throne. He married Rosamund to legitimize his position as new king, but immediately faced stiff opposition from his fellow Lombards who suspected Helmichis of conniving with the Byzantines; this hostility eventually focused around the duke of

20:

353:, the Empire's capital, together with Helmichis' forces, which were to become Byzantine mercenaries. This was a common Byzantine strategy, already applied previously to the Ostrogoths, by which large national contingents were relocated to be used in other theatres. These are believed to be the same 60,000 Lombards that are attested by

246:

tradition, it would be

Helmichis who was seduced by the queen, and by sleeping with him Rosamund would pass Alboin's royal charisma magically to the king's prospective murderer. A symbol of this passage of powers is found in Paul's account of the assassin's entry: Alboin's inability to draw his sword represents here his loss of power.

56:, supported or at least did not oppose Helmichis' plan to remove the king, and after the assassination Helmichis married her. The assassination was assisted by Peredeo, the king's chamber-guard, who in some sources becomes the material executer of the murder. Helmichis is first mentioned by the contemporary chronicler

142:

The oldest author to write about

Helmichis is the contemporary chronicler Marius of Avenches. In his account he mentions that "Alboin was killed by his followers, that is Hilmaegis with the rest, his wife agreeing to it". Marius continues by adding that, after killing the king, Helmichis married his

283:

Behind the coup were almost certainly the

Byzantines, who had every interest in removing a dangerous enemy and replacing him with somebody, if not from a pro-Byzantine faction, at least less actively aggressive. Gian Piero Bognetti advances a few hypotheses about Helmichis' motivation for his coup:

345:

Once in

Ravenna, Helmichis and Rosamund rapidly became estranged. According to Paul, Longinus persuaded Rosamund to get rid of her husband so that he could marry her. To accomplish this, she made him drink a cup full of poison; before dying, however, Helmichis understood what his wife had done and

324:

to

Byzantine-held Ravenna, together with his wife, his Lombard and Gepid troops, the royal treasure and Albsuinda. Bognetti believes that Longinus may have planned to make the Lombards weaker by depriving them of any legitimate heir. In addition, because of the ongoing war, it was hard to assemble

315:

Helmichis' coup ultimately failed because it met strong opposition from the many

Lombards who wanted to continue the war against the Byzantines and to confront the regicides. Faced with the prospect of going to war at overwhelming odds, Helmichis asked for help from the Byzantines. The praetorian

253:

in Verona. The marriage was important for

Helmichis: it legitimized his rule because, judging from Lombard history, royal prerogatives could be inherited by marrying the king's widow; and the marriage was a guarantee for Helmichis of the loyalty of the Gepids in the army, who sided with the queen

245:

According to historian Paolo Delogu it may be that

Agnellus' narrative better reflects Lombard oral tradition than Paul's. In his interpretation, Paul's narrative represents a late distortion of the Germanic myths and rituals contained in the oral tradition. In a telling consistent with Germanic

241:

may have been to obtain a more straightforward and coherent narrative by reducing the number of actors in the story, beginning with

Peredeo. The disappearance of Peredeo, however, means that the role of Helmichis changes: while Paul presents him as "the efficient conspirator and killer", with

209:

By settling himself in Verona and temporarily interrupting his chain of conquests, Alboin had weakened his popular standing as a charismatic warrior king. The first to take advantage of this was Rosamund, who could count on the support of the Gepid warriors in the town in her search for an

237:, where it is added that Peredeo was Alboin's "chamber-guard", hinting that in the original version of the story Peredeo's role may just have been to let in the real assassin, who is Helmichis in Agnellus' account, as it had been in that of Marius. However, the primary intent of the

110:

to kill Helmichis in order to be free to marry him. Rosamund proceeded to poison Helmichis, but the latter, having understood what his wife had done to him, forced her to drink the cup too, so both of them died. After their deaths, Longinus dispatched Helmichis' forces to

143:

widow and tried unsuccessfully to gain the throne. His attempt failed and he was forced to escape together with his wife, the royal treasure and the troops that had sided with him in the coup. This account has strong similarities with what is told in the

186:. After the fall of Ticinum, Alboin chose Verona as his first permanent headquarters. In this town Alboin was assassinated in 572 and it is in these circumstances that Helmichis' name is first heard of. Most of the available details are in the

520:

point of view. The second was written in the 830s by a priest from Ravenna and is a history of the bishops who held the see of Ravenna through the ages. Agnellus' passage on Alboin and Rosamund is mostly derived from Paul and little else.

384:

and making the Lombards who remained in Italy more vulnerable to attacks from Franks and Byzantines. It was only when faced with the danger of annihilation by the Franks in 584 that the Lombard dukes elected a new king in the person of

216:(arms bearer) and foster brother of the king, and also head of a personal armed retinue in Verona, to take part in a plot to eliminate Alboin and replace him on the throne. Helmichis persuaded Rosamund to involve

482:

serves to consolidate the Lombards' national identity by emphasising a shared history. Apart from the origin myth, the only more detailed account is the one concerning the death of Alboin, and thus Helmichis.

166:

and captured the king's daughter Rosamund – later marrying her to guarantee the loyalty of the surviving Gepids. The following year, the Lombards migrated to Italy, a territory then held by the

329:

king, having it in mind to continue Alboin's aggressive policy. In contrast, Wolfram argues that Cleph was elected in Ticinum while Helmichis was still making his bid for the crown in Verona.

158:

The background to the assassination begins when Alboin, king of the Lombards, a Germanic people living in Pannonia (in the region of modern Hungary), went to war against the neighbouring

426:

424:, though short, to be reliable on Italian matters. The remaining sources all come from Italy and were written in later centuries. Two of them were written in the 7th century, the

456:. This is the earliest surviving work to name Rosamund, the queen of the Lombards who plays a central role in Helmichis' attested biography. The other 7th century work, the

369:

probably aimed to use her as a political tool to impose a pro-Byzantine king on the Lombards. According to Agnellus, once Longinus' actions came to the attention of emperor

416:. Because of the small distance from Aventicum to the Italian peninsula, the chronicler had easy access to information regarding northern Italy. For this reason, historian

174:(Milan), the capital of northern Italy, and by 570 he had assumed control of most of northern Italy. The Byzantine forces entrenched themselves in the strategic town of

494:, what Paul deals with is an example of how nationally vital events were personalized to make them easier to preserve in the collective memory. Even later than the

317:

107:

440:

is a chronicle written around 625 that has reached us in a single manuscript. As its name suggests, it is a continuation of the 5th century chronicle of

220:, described by Paul simply as "a very strong man", who was seduced through a trick by the Queen and forced to consent to become the actual assassin.

452:, it blames the Romans for their inability to defend Italy from foreign invaders, and praises the Lombards for defending the country from the

325:

all the warriors to elect a new king formally. This plan was brought to nothing by the troops stationed in Ticinum, who elected their duke

1222:

Regna and Gentes: The Relationship between Late Antique and Early Medieval Peoples and Kingdoms in the Transformation of the Roman World

460:, is a brief prose history of the Lombards that is essentially an annotated king list, although it begins with a description of the

1249:

500:

233:

1350:

1320:

1281:

1258:

1241:

1180:

1112:

1452:

103:, where they were received with full honours by the authorities. Once in Ravenna, Rosamund was persuaded by the Byzantine

1427:

304:. Helmichis easily obtained the support of the Lombards in Verona, and he probably hoped to sway all the warriors and

1409:

1383:

1365:

1335:

1199:

1157:

1131:

1089:

1063:

1041:

1013:

974:

136:

498:, but possibly using earlier lost sources, are the last two primary sources to speak about Helmichis: the anonymous

1172:

1008:(in Latin and Italian). Introduzione, testo critico, commento. Roma: Herder editrice e libreria. pp. 1–22.

1462:

1401:

1312:

312:, under his control. He may also have hoped for Byzantine help in buying the dukes' loyalty economically.

1442:

1273:

1033:

1142:

The Narrators of Barbarian History (A.D. 550–800): Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede, and Paul the Deacon

1432:

1149:

1104:

432:

377:

178:(Pavia), which they took only after a long siege. Even before taking Ticinum, the Lombards crossed the

132:

1345:. Yitzhak Hen & Matthew Innes (eds.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp. 9–28.

993:

Bognetti, Gian Piero. "I rapporti etico-politici fra Oriente e Occidente dalsecolo V al secolo VIII",

1447:

1264:

Muhlberger, Steven. "War, Warlords, and Christian Historians from the Fifth to the Seventh Century",

1055:

983:

Bognetti, Gian Piero. "S. Maria Foris Portas di Castelseprio e la Storia Religiosa dei Longobardi",

380:. An important success for the Byzantines was that no king was proclaimed to succeed him, opening a

320:

enabled him to avoid a land route possibly held by hostile forces, by shipping him instead down the

78:

957:

Ausenda, Giorgio. "The Segmentary Lineage in Contemporary Anthropology and Among the Langobards",

401:

sources, there are six that mention Helmichis by name. Of these, the only contemporary one is the

389:, son of Cleph, who began the definitive consolidation and centralization of the Lombard kingdom.

250:

66:

227:, which has Peredeo acting as an instigator and not as the murderer. In a similar vein to the

1297:

1145:

341:

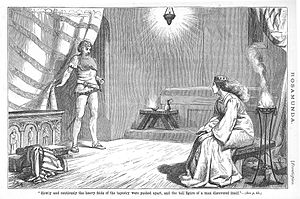

A miniature of Longinus, the Byzantine official said by Paul to be behind's Helmichis' death

210:

opportunity to avenge the death of her father. To obtain this goal she persuaded Helmichis,

1397:

1081:

441:

202:

Alboin is killed by Peredeo while Rosamund steals his sword, in a 19th-century painting by

100:

486:

For the events surrounding 572, the most exhaustive source available is Paul the Deacon's

8:

1437:

1371:

1308:

966:

962:

413:

366:

1022:

517:

449:

179:

104:

57:

1457:

1405:

1379:

1361:

1346:

1331:

1316:

1277:

1254:

1237:

1195:

1176:

1153:

1127:

1108:

1085:

1059:

1037:

1009:

970:

398:

381:

1233:

509:

249:

After the king's death on June 28, 572, Helmichis married Rosamund and claimed the

203:

167:

53:

77:

in 567 and captured the king's daughter Rosamund. Alboin then led his people into

1287:

470:

362:

354:

61:

337:

1389:

1291:

1137:

491:

350:

305:

112:

24:

1187:

373:

they were greatly praised, and the emperor gave lavish gifts to his official.

73:

The background to the assassination begins when Alboin killed the king of the

1421:

1069:

461:

417:

95:

Rather than going to war, Helmichis, Rosamund and their followers escaped to

1360:. Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis (ed.). Leiden: Brill, 2003, pp. 89–114.

1168:

52:, in 572 and unsuccessfully attempted to usurp his throne. Alboin's queen,

1330:. Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis (ed.). Leiden: Brill, 2003, pp. 43–87.

288:, the Lombard royal dynasty that had been dispossessed by Alboin's father

198:

1225:

475:

358:

1004:

Bracciotti, Annalisa (1998). "Premessa". In Bracciotti, Annalisa (ed.).

376:

Cleph kept his throne for only 18 months before being assassinated by a

1326:

Pizarro, Joaquin Martinez. "Ethnic and National History ca. 500–1000",

1029:

321:

212:

171:

1100:

406:

370:

309:

293:

127:

1300:(translator). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1907.

285:

163:

45:

1266:

After Rome's fall: narrators and sources of early medieval history

1250:

Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire – Volume III: A.D. 527–641

1194:(in Italian). Translated by Guglielmotti, Paola. Torino: Einaudi.

1269:

405:

of Marius of Avenches, written in the 580s. Marius was bishop of

386:

349:

At this point, Longinus sent the royal treasure and Albsuinda to

217:

175:

96:

86:

40:

1229:

1077:

453:

410:

289:

183:

159:

115:, while the remaining Lombards had already found a new king in

82:

74:

60:, but the most detailed account of his endeavours derives from

49:

1376:

Early Medieval Italy: Central Power and Local Society 400–1000

1341:

Pohl, Walter. "Memory, identity and power in Lombard Italy",

1165:

Barbarian Tides: The Migration Age and the Later Roman Empire

1123:

1122:. Paolo Delogu, André Guillou & Gherardo Ortalli (eds.).

326:

301:

297:

242:

Agnellus he is a victim of a ruthless and domineering queen.

116:

89:

516:

that was made in the first decade of the 9th century from a

19:

1356:

Sot, Michel. "Local and Institutional History (300–1000)",

1305:

Writing Ravenna: the Liber pontificalis of Andreas Agnellus

162:

in 567. In a decisive battle, Alboin killed the Gepid king

223:

This story is partly in conflict with what is told by the

959:

After Empire: Towards an Ethnology of Europe's Barbarians

464:

of the Lombard nation. Giorgio Ausenda believes that the

92:, supporter of an aggressive policy towards the Empire.

512:. The first is a brief Christianizing version of the

474:, and continued to be updated till 671. According to

698:

696:

284:

his reason could have involved a family link to the

1378:. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1981 ,

693:

478:, the author's motives are mostly political: the

151:would in its turn become a direct source for the

1419:

1253:, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992,

23:Helmichis discovering himself to Rosamund from

1343:The uses of the past in the early Middle Ages

1050:Capo, Lidia. "Commento" in Paul the Deacon,

468:was written around 643 as a prologue to the

409:, a town located in the western Alps in the

392:

444:. Derived in considerable measure from the

308:to his side by having Alboin's only child,

231:is the account of Peredeo contained in the

1003:

712:

710:

708:

1394:The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples

1026:Carolingian Renewal: Sources and Heritage

987:. Milan: Giuffrè, 1948 , pp. 11–511.

686:

684:

568:

566:

747:

745:

336:

197:

126:

18:

997:. Milan: Giuffrè, 1955 , pp. 3–65.

770:

768:

766:

726:

724:

722:

705:

656:

654:

644:

642:

506:Liber Pontificalis Ecclesiae Ravennatis

1420:

1224:. Hans-Wener Goetz, Jörg Jarnut &

1186:

1118:Delogu, Paolo. "Il regno longobardo",

681:

589:

587:

563:

543:

541:

539:

537:

535:

533:

501:Historia Langobardorum codicis Gothani

292:; or he may have been related through

239:Historia Langobardorum codicis Gothani

234:Historia Langobardorum codicis Gothani

742:

619:

617:

763:

719:

651:

639:

81:, and by 572 had settled himself in

858:

584:

530:

254:since she was Cunimund's daughter.

13:

614:

14:

1474:

1358:Historiography in the Middle Ages

1328:Historiography in the Middle Ages

1173:University of Pennsylvania Press

261:

193:

1126:: UTET, 1980 , pp. 1–216.

939:

930:

921:

912:

903:

894:

885:

876:

867:

849:

840:

831:

822:

813:

804:

795:

786:

777:

754:

733:

672:

663:

427:Continuatio Havniensis Prosperi

1402:University of California Press

1095:Deliyannis, Deborah Mauskopf.

1074:Early Medieval Europe 300–1000

716:Wolfram 1997, pp. 291–292

669:Goffart 1988, pp. 391–392

626:

605:

596:

575:

572:Collins 1991, pp. 187–188

554:

1:

1268:. Alexander C. Murray (ed.).

951:

792:Bognetti 1968, pp. 28–29

760:Bognetti 1966, pp. 73–74

611:Bognetti 1968, pp. 27–28

300:, the leading dynasty of the

122:

1313:University of Michigan Press

900:Pizarro 2003, pp. 72–73

810:Wickham 1989, pp. 31–32

7:

1453:Assassins of heads of state

1303:Pizarro, Joaquin Martinez.

1274:University of Toronto Press

1247:Martindale, John R. (ed.),

1054:. Lidia Capo (ed.). Milan:

1034:Manchester University Press

751:Wolfram 1997, pp. 291 – 292

702:Delogu 2003, pp. 16–17

623:Jarnut 1995, pp. 29–30

131:Rosamund, as viewed by the

48:noble who killed his king,

10:

1479:

1428:6th-century Lombard people

1236:, 2003, pp. 409–427.

1150:Princeton University Press

1105:Cambridge University Press

1058:, 1992, pp. 369–612.

1006:Origo gentis Langobardorum

433:Origo Gentis Langobardorum

257:

1293:History of the Langobards

1097:Ravenna in Late Antiquity

969:, 1995 , pp. 15–45.

961:. Giorgio Ausenda (ed.).

393:Early Middle Ages sources

1276:, 1998, pp. 83–98.

524:

365:. As for Albsuinda, the

332:

593:Deliyannis 2010, p. 203

1120:Longobardi e Bizantini

837:Muhlberger 1998, p. 96

496:Historia Langobardorum

488:Historia Langobardorum

436:, both anonymous. The

342:

275:Historia Langobardorum

206:

188:Historia Langobardorum

153:Historia Langobardorum

139:

67:Historia Langobardorum

32:

29:Rosamunda The Princess

1463:6th-century criminals

1298:William Dudley Foulke

1192:Storia dei Longobardi

1052:Storia dei Longobardi

995:L'età longobarda – IV

985:L'età longobarda – II

581:Bullough 1991, p. 107

382:decade of interregnum

340:

201:

170:. In 569 Alboin took

130:

64:'s late 8th-century

22:

945:Pizarro 1995, p. 131

909:Wolfram 1997, p. 292

882:Braciotti 1998, p. 8

846:Goffart 1988, p. 391

828:Collins 1991, p. 187

819:Goffart 2006, p. 254

783:Pizarro 1995, p. 127

774:Bognetti 1966, p. 74

690:Pizarro 1995, p. 133

678:Pizarro 1995, p. 132

660:Pizarro 1995, p. 128

442:Prosper of Aquitaine

397:Among the surviving

1023:Bullough, Donald A.

891:Pizarro 2003, p. 70

864:Ausenda 2003, p. 34

414:Kingdom of Burgundy

367:Byzantine diplomacy

361:in 575 against the

357:as being active in

1443:Medieval assassins

1220:of the Lombards",

1163:Goffart, Walter.

730:Jarnut 1995, p. 32

648:Delogu 2003, p. 16

602:Jarnut 1995, p. 22

450:Isidore of Seville

343:

277:, Book II, Ch. 29

207:

140:

58:Marius of Avenches

33:

1433:Italian regicides

1351:978-0-521-63998-9

1321:978-0-472-10606-6

1282:978-0-8020-0779-7

1259:978-0-521-20160-5

1242:978-90-04-12524-7

1181:978-0-8122-3939-3

1113:978-0-521-83672-2

918:Capo 1992, p. 452

801:Capo 1992, p. 454

632:Martindale 1992,

560:Paul 1907, p. 83n

547:Martindale 1992,

399:Early Middle Ages

281:

280:

99:, the capital of

1470:

1448:Lombard warriors

1208:Jarnut, Jörg. "

1205:

1049:

1019:

1002:

992:

982:

946:

943:

937:

936:Sot 2003, p. 104

934:

928:

927:Pohl 2000, p. 21

925:

919:

916:

910:

907:

901:

898:

892:

889:

883:

880:

874:

873:Pohl 2000, p. 16

871:

865:

862:

856:

855:Pohl 2000, p. 15

853:

847:

844:

838:

835:

829:

826:

820:

817:

811:

808:

802:

799:

793:

790:

784:

781:

775:

772:

761:

758:

752:

749:

740:

739:Paul 1907, p. 84

737:

731:

728:

717:

714:

703:

700:

691:

688:

679:

676:

670:

667:

661:

658:

649:

646:

637:

636:, pp. 38–40

630:

624:

621:

612:

609:

603:

600:

594:

591:

582:

579:

573:

570:

561:

558:

552:

545:

510:Andreas Agnellus

262:

204:Charles Landseer

168:Byzantine Empire

137:Frederick Sandys

16:Italian regicide

1478:

1477:

1473:

1472:

1471:

1469:

1468:

1467:

1418:

1417:

1390:Wolfram, Herwig

1288:Paul the Deacon

1202:

1138:Goffart, Walter

1047:

1016:

1000:

990:

980:

954:

949:

944:

940:

935:

931:

926:

922:

917:

913:

908:

904:

899:

895:

890:

886:

881:

877:

872:

868:

863:

859:

854:

850:

845:

841:

836:

832:

827:

823:

818:

814:

809:

805:

800:

796:

791:

787:

782:

778:

773:

764:

759:

755:

750:

743:

738:

734:

729:

720:

715:

706:

701:

694:

689:

682:

677:

673:

668:

664:

659:

652:

647:

640:

631:

627:

622:

615:

610:

606:

601:

597:

592:

585:

580:

576:

571:

564:

559:

555:

546:

531:

527:

471:Edictum Rothari

446:Chronica Majora

395:

355:John of Ephesus

335:

273:

271:Paul the Deacon

260:

196:

125:

101:Byzantine Italy

62:Paul the Deacon

27:'s publication

17:

12:

11:

5:

1476:

1466:

1465:

1460:

1455:

1450:

1445:

1440:

1435:

1430:

1414:

1413:

1387:

1372:Wickham, Chris

1369:

1354:

1339:

1324:

1301:

1285:

1262:

1245:

1206:

1200:

1184:

1161:

1135:

1116:

1093:

1070:Collins, Roger

1067:

1045:

1020:

1014:

998:

988:

978:

953:

950:

948:

947:

938:

929:

920:

911:

902:

893:

884:

875:

866:

857:

848:

839:

830:

821:

812:

803:

794:

785:

776:

762:

753:

741:

732:

718:

704:

692:

680:

671:

662:

650:

638:

625:

613:

604:

595:

583:

574:

562:

553:

528:

526:

523:

492:Herwig Wolfram

420:considers the

394:

391:

351:Constantinople

334:

331:

279:

278:

267:

266:

259:

256:

251:Lombard throne

195:

192:

133:Pre-Raphaelite

124:

121:

113:Constantinople

25:Anna Kingsford

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1475:

1464:

1461:

1459:

1456:

1454:

1451:

1449:

1446:

1444:

1441:

1439:

1436:

1434:

1431:

1429:

1426:

1425:

1423:

1416:

1411:

1410:0-520-24490-7

1407:

1403:

1399:

1395:

1391:

1388:

1385:

1384:0-472-08099-7

1381:

1377:

1373:

1370:

1367:

1366:90-04-11881-0

1363:

1359:

1355:

1352:

1348:

1344:

1340:

1337:

1336:90-04-11881-0

1333:

1329:

1325:

1322:

1318:

1314:

1310:

1306:

1302:

1299:

1295:

1294:

1289:

1286:

1283:

1279:

1275:

1271:

1267:

1263:

1260:

1256:

1252:

1251:

1246:

1243:

1239:

1235:

1231:

1227:

1223:

1219:

1215:

1211:

1207:

1203:

1201:88-06-13658-5

1197:

1193:

1189:

1185:

1182:

1178:

1174:

1170:

1166:

1162:

1159:

1158:0-691-05514-9

1155:

1151:

1147:

1143:

1139:

1136:

1133:

1132:88-02-03510-5

1129:

1125:

1121:

1117:

1114:

1110:

1106:

1102:

1098:

1094:

1091:

1090:0-333-36825-8

1087:

1083:

1079:

1075:

1071:

1068:

1065:

1064:88-04-33010-4

1061:

1057:

1053:

1046:

1043:

1042:0-7190-3354-3

1039:

1035:

1031:

1027:

1024:

1021:

1017:

1015:88-85876-32-3

1011:

1007:

999:

996:

989:

986:

979:

976:

975:0-85115-853-6

972:

968:

964:

960:

956:

955:

942:

933:

924:

915:

906:

897:

888:

879:

870:

861:

852:

843:

834:

825:

816:

807:

798:

789:

780:

771:

769:

767:

757:

748:

746:

736:

727:

725:

723:

713:

711:

709:

699:

697:

687:

685:

675:

666:

657:

655:

645:

643:

635:

629:

620:

618:

608:

599:

590:

588:

578:

569:

567:

557:

550:

549:s.v. Hilmegis

544:

542:

540:

538:

536:

534:

529:

522:

519:

515:

511:

507:

503:

502:

497:

493:

489:

484:

481:

477:

473:

472:

467:

463:

462:founding myth

459:

455:

451:

447:

443:

439:

435:

434:

429:

428:

423:

419:

418:Roger Collins

415:

412:

408:

404:

400:

390:

388:

383:

379:

374:

372:

368:

364:

360:

356:

352:

347:

339:

330:

328:

323:

319:

313:

311:

307:

306:Lombard dukes

303:

299:

295:

291:

287:

276:

272:

269:

268:

264:

263:

255:

252:

247:

243:

240:

236:

235:

230:

226:

221:

219:

215:

214:

205:

200:

194:Assassination

191:

189:

185:

181:

177:

173:

169:

165:

161:

156:

154:

150:

146:

138:

134:

129:

120:

118:

114:

109:

106:

102:

98:

93:

91:

88:

84:

80:

76:

71:

69:

68:

63:

59:

55:

51:

47:

43:

42:

37:

30:

26:

21:

1415:

1393:

1375:

1357:

1342:

1327:

1304:

1292:

1265:

1248:

1221:

1217:

1213:

1209:

1191:

1188:Jarnut, Jörg

1169:Philadelphia

1164:

1141:

1119:

1096:

1073:

1051:

1048:(in Italian)

1025:

1005:

1001:(in Italian)

994:

991:(in Italian)

984:

981:(in Italian)

958:

941:

932:

923:

914:

905:

896:

887:

878:

869:

860:

851:

842:

833:

824:

815:

806:

797:

788:

779:

756:

735:

674:

665:

633:

628:

607:

598:

577:

556:

548:

513:

505:

499:

495:

487:

485:

479:

469:

465:

457:

445:

437:

431:

425:

421:

402:

396:

375:

348:

344:

314:

282:

274:

270:

248:

244:

238:

232:

228:

224:

222:

211:

208:

187:

182:and invaded

157:

152:

148:

144:

141:

94:

72:

65:

39:

35:

34:

28:

1226:Walter Pohl

634:s.v. Alboin

518:Carolingian

508:written by

476:Walter Pohl

438:Continuatio

44:572) was a

1438:572 deaths

1422:Categories

1030:Manchester

963:Woodbridge

952:References

213:spatharius

172:Mediolanum

123:Background

1404:, 1990 ,

1309:Ann Arbor

1190:(1995) .

1146:Princeton

1101:Cambridge

1082:Macmillan

1056:Mondadori

407:Aventicum

371:Justin II

310:Albsuinda

294:Amalafrid

180:Apennines

36:Helmichis

1458:Usurpers

1398:Berkeley

1315:, 1995,

1228:(eds.).

1175:, 2006,

1152:, 1988,

1107:, 2010,

1084:, 1991,

1036:, 1991,

551:, p. 599

504:and the

430:and the

422:Chronica

411:Frankish

403:Chronica

363:Persians

318:Longinus

316:prefect

286:Lethings

164:Cunimund

108:Longinus

54:Rosamund

1270:Toronto

967:Boydell

387:Authari

296:to the

258:Failure

218:Peredeo

176:Ticinum

135:artist

105:prefect

97:Ravenna

87:Ticinum

46:Lombard

1408:

1382:

1364:

1349:

1334:

1319:

1280:

1257:

1240:

1230:Leiden

1218:regnum

1198:

1179:

1156:

1130:

1111:

1088:

1078:London

1062:

1040:

1012:

973:

454:Franks

290:Audoin

184:Tuscia

160:Gepids

147:. The

83:Verona

75:Gepids

50:Alboin

31:(1875)

1234:Brill

1124:Turin

525:Notes

514:Origo

480:Origo

466:Origo

458:Origo

378:slave

359:Syria

333:Death

327:Cleph

302:Goths

298:Amali

229:Origo

225:Origo

149:Origo

145:Origo

117:Cleph

90:Cleph

79:Italy

1406:ISBN

1380:ISBN

1362:ISBN

1347:ISBN

1332:ISBN

1317:ISBN

1278:ISBN

1255:ISBN

1238:ISBN

1216:and

1210:Gens

1196:ISBN

1177:ISBN

1154:ISBN

1128:ISBN

1109:ISBN

1086:ISBN

1060:ISBN

1038:ISBN

1010:ISBN

971:ISBN

1214:rex

448:of

41:fl.

1424::

1400::

1396:.

1392:.

1374:.

1311::

1307:.

1296:.

1290:.

1272::

1232::

1212:,

1171::

1167:.

1148::

1144:.

1140:.

1103::

1099:.

1080::

1076:.

1072:.

1032::

1028:.

965::

765:^

744:^

721:^

707:^

695:^

683:^

653:^

641:^

616:^

586:^

565:^

532:^

322:Po

190:.

155:.

119:.

70:.

1412:.

1386:.

1368:.

1353:.

1338:.

1323:.

1284:.

1261:.

1244:.

1204:.

1183:.

1160:.

1134:.

1115:.

1092:.

1066:.

1044:.

1018:.

977:.

38:(

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.