151:

29:

100:

331:, who produced a variety of Cauliflower, Pineapple, Fruit Basket and other popular wares. There was considerable inventiveness of form and the use of moulds allowed both greater complexity and ease of mass-production. Several creamware types used moulds originally produced for the earlier salt-glazed stoneware goods, such as the typical plates illustrated opposite. Combined with increasingly sophisticated decorative techniques, creamware quickly became established as the preferred ware for the dinner table amongst both middle and upper classes.

271:

210:

340:

434:

374:

169:. and to the United States. One contemporary writer and friend of Wedgwood claimed it was ubiquitous. This led to local industries developing throughout Europe to meet demand. There was also a strong export market to the United States. The success of creamware had killed the demand for tin-glazed earthenware and pewter vessels alike and the spread of cheap, good-quality, mass-produced creamware to Europe had a similar impact on Continental tin-glazed

454:

In addition, factories usually sent out their wares to outside specialist enamellers or transfer-printers for decoration – decoration in-house was only gradually adopted. For this reason, several manufacturers usually shared the same decorator or printer and tended to use the same or very similar patterns.

453:

Attribution of pieces to particular factories has always been difficult because virtually no creamware was marked prior to Josiah

Wedgwood's manufacture of it in Burslem. At the time manufacturers frequently supplied wares to one another to supplement stocks and ideas were often exchanged or copied.

424:

By 1760 creamware was often enamelled for decoration, using a technique adopted from the early porcelain industry. This consisted of painting overglaze on the ware with pigments made from finely powdered coloured glass and then firing again to fuse the enamel to the ware. The varied enamel colours

400:

was prepared and rubbed with oil. The surplus oil was wiped off and an impression was taken onto thin paper. The oily print was then transferred to the glazed earthenware surface which was then dusted with finely ground pigment in the chosen colour. Excess powder was then removed and the ware was

355:

The early process of using lead-powder produced a brilliant, transparent glaze of a rich cream colour. Small stamped motifs similar to those used at the time on salt-glaze wares and redware were sometimes applied to the ware for decoration. Dry crystals of metallic oxides such as copper, iron and

230:, mixed with a certain amount of ground calcined flint, was dusted on the ware, which was then given its one and only firing. This early method was unsatisfactory because the use of lead componds resulted in lead poisoning among the potters, and the dry grinding of calcined flint caused a form of

364:

The early lead-powder process led directly to the development of the tortoiseshell method and other coloured glazes which were used with the new fluid glazes. Here, patches of colour were sponged or painted onto the biscuit surface before a clear glaze was applied to the whole and then fired.

449:

Whilst

Staffordshire had taken the lead, creamware came to be developed in a number of large potting centres where stoneware was already being produced, eventually replacing stoneware entirely. These included Derbyshire, Liverpool, Yorkshire (including the Leeds pottery) and Swansea.

457:

Collectors, dealers and curators alike were frustrated in their efforts to ascribe pots to individual factories: it is frequently impossible to do so. Archaeological excavations of pottery sites in

Staffordshire and elsewhere have helped provide some better-established

494:

The heyday of creamware ran from about 1770 to the rise of painted pearlwares, white wares and stone chinas in the period around 1810 to 1825. Although creamware continued to be produced during the later period, it was no longer pre-eminent in the markets.

412:

that could be laid on the workbench whilst a globular pot was carefully rolled over it. Glue-bats allowed more subtle engraving techniques to be used. Underglaze transfer printing was also sometimes used, directly onto the porous biscuit body.

282:

into both the body and glaze and so was able to produce creamware of a much paler colour, lighter and stronger and more delicately worked, perfecting the ware by about 1770. His superior creamware, known as 'Queen's ware', was supplied to

241:

in which the ingredients were mixed and ground in water was invented, possibly by Enoch Booth of

Tunstall, Staffordshire, according to one early historian, although this is disputed. The method involved first firing the ware to a

201:

to form a cream-coloured earthenware. The white clays ensured a white colour after firing and the addition of calcined flint improved its thermal shock resistance, whilst the calcined flint in the glazes helped prevent

445:

There were approximately 130 potteries in North

Staffordshire during the 1750s, rising to around 150 by 1763 and employing up to 7,000 people – a large number of these potteries would have been producing creamware.

264:

was in partnership with Thomas

Whieldon from 1754 to 1759 and after Wedgwood had left to set up independently at Ivy House, he immediately directed his efforts to the development of creamware.

274:

Fragment of moulded 18th-century creamware found on Thames foreshore, central London, August 2017. Showing typical patterns of border decoration. Staffordshire, c. 1760–1780. Courtesy C Hobey.

257:. Although he has become popularly associated almost exclusively with tortoiseshell creamware, in fact he produced a wide variety of creamware. He first mentions 'Cream Colour' in 1749.

416:

Transfer-printing was specialist and so generally outsourced in the early years: Sadler & Green of

Liverpool were exclusive printers to Josiah Wedgwood by 1763, for example.

267:

Wedgwood rebelled against the use of coloured glazes, declaring as early as 1766 that he was clearing his warehouse of coloured ware as he was 'heartily sick of the commodity'.

150:

311:

amongst the growing middle classes of the time. By around 1808 a fully whitened version of creamware (known as White Ware) was introduced to meet changing market demand.

307:

and a body somewhat modified to produce a ware that was slightly greyish in appearance. Pearlware was developed in order to meet demand for substitutes for

Chinese

291:

and later became hugely popular. There were few changes to creamware after about 1770 and the

Wedgwood formula was gradually adopted by most manufacturers.

303:, of which there was an increase around 1779. Pearlware is distinct from creamware in having a blue-tinged glaze produced by the use of

343:

An early tortoiseshell-decorated creamware plate. Perhaps from the factory of Thomas

Whieldon, but not attributable. Private collection

598:

The Chemistry of the several natural and artificial heterogeneous compounds used in manufacturing porcelain, glass, and pottery, etc..

327:

from 1754 to 1759, moulded creamware in a variety of forms was developed, especially in collaboration with the talented block-cutter

1032:

A R Mountford, "Thomas Whieldon's Manufactory at Fenton Vivian," Transactions of the English Ceramic Circle, Vol. 8 pt. 2 (1972)

583:

Osborne, 140; Creamware for the American market is the subject of Patricia A. Halfpenny, Robert S. Teitelman and Ronald Fuchs,

1151:

1120:

1095:

1050:

1020:

999:

978:

931:

910:

824:

798:

738:

706:

685:

618:

639:

162:

Wedgwood and his English competitors sold creamware throughout Europe, sparking local industries, that largely replaced

284:

115:, who perfected the ware, beginning during his partnership with Thomas Whieldon. Wedgwood supplied his creamware to

197:, but it is fired to a lower temperature (around 800 °C as opposed to 1,100 to 1,200 °C) and glazed with

84:

Variations of creamware were known as "tortoiseshell ware" or "Whieldon ware" were developed by the master potter

1188:

1134:

1071:

1090:

The Fifth Exhibition from the Northern Ceramic Society. Stoke-on-Trent City Museum & Art Gallery (1986).

1015:

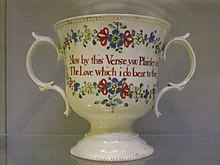

The Fifth Exhibition from the Northern Ceramic Society. Stoke-on-Trent City Museum & Art Gallery (1986).

926:

The Fifth Exhibition from the Northern Ceramic Society. Stoke-on-Trent City Museum & Art Gallery (1986).

905:

The Fifth Exhibition from the Northern Ceramic Society. Stoke-on-Trent City Museum & Art Gallery (1986).

701:

The Fifth Exhibition from the Northern Ceramic Society. Stoke-on-Trent City Museum & Art Gallery (1986).

793:

The Fifth Exhibition from the Northern Ceramic Society. Stoke-on-Trent City Museum &Art Gallery (1986).

1183:

425:

did not fuse at the same temperature so several firings were generally needed, adding to the expense.

217:. Burslem, about 1771–1775. Printed by Guy Green, Liverpool. On display at the British Museum, London.

93:

1163:

408:

This method could be varied by transferring the oily print onto a 'glue-bat' – a slab of flexible

377:

Jug, c. 1765 by the Pont-aux-Choux factory near Paris, one of the first and best French makers of

365:

Coloured decoration could help disguise imperfections that might arise during the firing process.

250:

405:

to soften the glaze, burn off the oil and leave the printed image firmly bonded to the surface.

1139:

554:

482:("earthenware in the English manner"). They were produced in many factories, including by the

459:

397:

356:

manganese were then dusted onto the ware to form patches of coloured decoration during firing.

1075:

173:

factories. By the 1780s Josiah Wedgwood was exporting as much as 80% of his output to Europe.

697:

Gordon Elliot, "The Technical Characteristics of Creamware and Pearl-Glazed Earthenware," in

28:

1178:

514:

393:

89:

632:

Success to America: Creamware for the American Market. Woodbridge: Antiquw Collectors Club

131:. Later, around 1779, he was able to lighten the cream colour to a bluish white by using

8:

288:

120:

20:

328:

99:

70:

270:

88:

with coloured stains under the glaze. It served as an inexpensive substitute for the

1147:

1130:

1116:

1091:

1067:

1046:

1016:

995:

974:

927:

906:

820:

794:

734:

702:

681:

635:

614:

385:

214:

203:

92:

being developed by contemporary English manufactories, initially in competition with

209:

483:

243:

33:

339:

324:

320:

261:

254:

116:

112:

85:

517:

and the Triumph of Art and Industry (Bard Graduate Center, New York), Glossary,

36:

in purple enamel by Guy Green of Liverpool. Victoria & Albert Museum, London

901:

P Holdway, "Techniques of Transfer-printing on Cream Coloured Earthenware," in

402:

922:

N Stretton, "On-glaze Transfer-printing on Creamware: The first fifty Years,"

226:

Creamware was first produced some time before 1740. Originally lead powder or

1172:

238:

144:

96:. It was often made in the same fashionable and refined styles as porcelain.

62:

124:

433:

44:

373:

389:

104:

78:

74:

347:

Creamware during the 18th century was decorated in a variety of ways:

49:

16:

Cream-coloured, refined earthenware with a lead glaze over a pale body

308:

279:

231:

194:

163:

136:

388:

of pottery was developed in the 1750s. There were two main methods,

1064:

Italian Ceramics: Catalogue of the J. Paul Getty Museum Collections

409:

77:, which proved so ideal for domestic ware that it supplanted white

170:

166:

66:

304:

227:

182:

147:(producing "Leedsware") was another very successful producer.

132:

1086:

Terrence A Lockett, "The Later Creamwares and Pearlwares," in

73:

towards a finer, thinner, whiter body with a brilliant glassy

190:

186:

139:. Wedgwood sold this more desirable product under the name

630:

Patricia A Halfpenny, Robert S Teitelman and Ronald Fuchs,

198:

1062:

Hess, Catherine, with Marietta Cambereri on this entry,

853:, London: Victoria & Albert Museum (2005) pp. 91-93

47:

with a lead glaze over a pale body, known in France as

958:

The Pottery Trade and North Staffordshire 1660 – 1760.

585:

Success to America: Creamware for the American Market

193:. This body is the same as that used for salt-glazed

81:

wares by about 1780. It was popular until the 1840s.

947:, London: Victoria & Albert Museum (2005) p. 224

879:, London: Victoria & Albert Museum (2005) p. 228

866:, London: Victoria & Albert Museum (2005) p. 227

892:, London: Victoria & Albert Museum (2005) p. 86

840:, London: Victoria & Albert Museum (2005) p. 88

780:, London: Victoria & Albert Museum (2005) p. 80

767:, London: Victoria & Albert Museum (2005) p. 82

667:, London: Victoria & Albert Museum (2005) p. 93

1011:Terrence A Lockett, "Problems of Attribution," in

32:Josiah Wedgwood: Tea and coffee service, c. 1775.

213:Josiah Wedgwood: Four creamware plates depicting

1170:

1045:, Stoke-on-Trent: City Museum & Art Gallery

428:

61:. It was created about 1750 by the potters of

1115:, London: Victoria & Albert Museum (2005)

540:

538:

536:

534:

532:

69:, who refined the materials and techniques of

789:Pat Halfpenny, "Early Creamware to 1770," in

754:, Hanley, Printed for the author (1829), p 18

249:Foremost of the pioneers of creamware in the

472:Italian versions of creamware were known as

1164:Creamware at the Victoria and Albert Museum

1127:The Oxford Companion to the Decorative Arts

529:

278:Wedgwood improved creamware by introducing

176:

111:The most notable producer of creamware was

1066:, 2003, p. 244, note 1Getty Publications,

246:state, and then glazing and re-firing it.

158:) in three parts, 1770–1775, Queen's ware

960:Manchester University Press (1971), p. 5

432:

372:

338:

269:

208:

181:Creamware is made from white clays from

149:

98:

27:

521:"Creamware: "In France it was known as

359:

1171:

752:History of the Staffordshire Potteries

396:. For overglaze printing, an engraved

299:One important ware of note however is

811:

809:

807:

725:

723:

721:

719:

717:

715:

600:London: for the author (1837), p. 465

368:

234:colloquially known as potter's rot.

189:combined with an amount of calcined

1146:, London: Faber & Faber (1978)

994:, London: Faber & Faber (1978)

819:, London: Faber & Faber (1978)

733:, London: Faber & Faber (1978)

680:, London: Faber & Faber (1978)

613:, London: Faber & Faber (1978)

462:to enable progress in attribution.

13:

1105:

804:

712:

513:The Sėvres Porcelain Manufactory:

14:

1200:

1157:

19:For the synthesizer company, see

1041:David Barker and Pat Halfpenny,

1080:

1056:

1035:

1026:

1005:

984:

963:

950:

937:

916:

895:

882:

869:

856:

843:

830:

783:

770:

757:

744:

691:

670:

657:

319:During the partnership between

644:

624:

603:

590:

577:

564:

547:

505:

350:

221:

1:

511:Tamara Préaud, curator. 1997.

498:

429:Manufacturers and attribution

419:

334:

465:

294:

43:is a cream-coloured refined

7:

1113:English Pottery 1620 – 1840

973:. London: Macmillan (1992)

945:English Pottery 1620 – 1840

890:English Pottery 1620 – 1840

877:English Pottery 1620 – 1840

864:English Pottery 1620 – 1840

851:English Pottery 1620 – 1840

838:English Pottery 1620 – 1840

778:English Pottery 1620 – 1840

765:English Pottery 1620 – 1840

665:English Pottery 1620 – 1840

10:

1205:

971:Josiah Wedgwood, 1730-1795

553:The standard monograph is

489:

401:given a short firing in a

127:) and used the trade name

18:

381:, as creamware was known.

94:Chinese export porcelains

1088:Creamware and Pearlware.

1043:Unearthing Staffordshire

1013:Creamware and Pearlware.

924:Creamware and Pearlware.

903:Creamware and Pearlware.

791:Creamware and Pearlware.

699:Creamware and Pearlware.

561:(Faber & Faber) 1978

314:

177:Materials and production

53:, in the Netherlands as

251:Staffordshire Potteries

71:salt-glazed earthenware

1125:Osborne, Harold (ed),

442:

382:

344:

275:

218:

159:

108:

37:

1189:Staffordshire pottery

654:London: Hamlyn (1989)

480:creta all'uso inglese

436:

376:

342:

273:

212:

154:Wedgwood ice-bucket (

153:

102:

90:soft-paste porcelains

31:

515:Alexandre Brongniart

360:Tortoiseshell method

237:Around 1740 a fluid

652:European Creamware.

437:Le Nove (Venetian)

289:Catherine the Great

121:Catherine the Great

21:Creamware (company)

1184:English inventions

1111:Hildyard, Robin,

572:European Creamware

443:

383:

345:

329:William Greatbatch

276:

219:

160:

109:

57:, and in Italy as

38:

1074:, 9780892366705,

386:Transfer-printing

369:Transfer-printing

59:terraglia inglese

1196:

1099:

1084:

1078:

1060:

1054:

1039:

1033:

1030:

1024:

1009:

1003:

988:

982:

967:

961:

954:

948:

943:Robin Hildyard,

941:

935:

920:

914:

899:

893:

888:Robin Hildyard,

886:

880:

875:Robin Hildyard,

873:

867:

862:Robin Hildyard,

860:

854:

849:Robin Hildyard,

847:

841:

836:Robin Hildyard,

834:

828:

813:

802:

787:

781:

776:Robin Hildyard,

774:

768:

763:Robin Hildyard,

761:

755:

748:

742:

727:

710:

695:

689:

674:

668:

663:Robin Hildyard,

661:

655:

648:

642:

628:

622:

607:

601:

594:

588:

581:

575:

568:

562:

555:Donald C. Towner

551:

545:

542:

527:

509:

484:Naples porcelain

55:Engels porselein

34:Transfer-printed

1204:

1203:

1199:

1198:

1197:

1195:

1194:

1193:

1169:

1168:

1160:

1108:

1106:Further reading

1103:

1102:

1085:

1081:

1061:

1057:

1040:

1036:

1031:

1027:

1010:

1006:

990:Donald Towner,

989:

985:

968:

964:

956:L. Weatherill,

955:

951:

942:

938:

921:

917:

900:

896:

887:

883:

874:

870:

861:

857:

848:

844:

835:

831:

815:Donald Towner,

814:

805:

788:

784:

775:

771:

762:

758:

749:

745:

729:Donald Towner,

728:

713:

696:

692:

676:Donald Towner,

675:

671:

662:

658:

650:Jana Kybalova,

649:

645:

629:

625:

609:Donald Towner,

608:

604:

595:

591:

582:

578:

570:Jana Kybalova,

569:

565:

552:

548:

543:

530:

510:

506:

501:

492:

470:

431:

422:

371:

362:

353:

337:

325:Josiah Wedgwood

321:Thomas Whieldon

317:

297:

285:Queen Charlotte

262:Josiah Wedgwood

255:Thomas Whieldon

224:

179:

123:(in the famous

117:Queen Charlotte

113:Josiah Wedgwood

86:Thomas Whieldon

24:

17:

12:

11:

5:

1202:

1192:

1191:

1186:

1181:

1167:

1166:

1159:

1158:External links

1156:

1155:

1154:

1140:Towner, Donald

1137:

1123:

1107:

1104:

1101:

1100:

1079:

1055:

1034:

1025:

1004:

983:

969:Robin Reilly,

962:

949:

936:

915:

894:

881:

868:

855:

842:

829:

803:

782:

769:

756:

743:

711:

690:

669:

656:

643:

640:978 1851496310

623:

602:

589:

576:

563:

546:

528:

503:

502:

500:

497:

491:

488:

469:

464:

441:group, c. 1786

430:

427:

421:

418:

370:

367:

361:

358:

352:

349:

336:

333:

316:

313:

296:

293:

223:

220:

215:Aesop's Fables

178:

175:

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

1201:

1190:

1187:

1185:

1182:

1180:

1177:

1176:

1174:

1165:

1162:

1161:

1153:

1152:0 571 04964 8

1149:

1145:

1141:

1138:

1136:

1132:

1129:, 1975, OUP,

1128:

1124:

1122:

1121:1 85177 442 4

1118:

1114:

1110:

1109:

1097:

1096:0 905080 64 5

1093:

1089:

1083:

1077:

1073:

1069:

1065:

1059:

1052:

1051:0 905080 89 0

1048:

1044:

1038:

1029:

1022:

1021:0 905080 64 5

1018:

1014:

1008:

1001:

1000:0 571 04964 8

997:

993:

987:

980:

979:0 333 51041 0

976:

972:

966:

959:

953:

946:

940:

933:

932:0 905080 64 5

929:

925:

919:

912:

911:0 905080 64 5

908:

904:

898:

891:

885:

878:

872:

865:

859:

852:

846:

839:

833:

826:

825:0 571 04964 8

822:

818:

812:

810:

808:

800:

799:0 905080 64 5

796:

792:

786:

779:

773:

766:

760:

753:

750:Simeon Shaw,

747:

740:

739:0 571 04964 8

736:

732:

726:

724:

722:

720:

718:

716:

708:

707:0 905080 64 5

704:

700:

694:

687:

686:0 571 04964 8

683:

679:

673:

666:

660:

653:

647:

641:

637:

633:

627:

620:

619:0 571 04964 8

616:

612:

606:

599:

596:Simeon Shaw,

593:

586:

580:

573:

567:

560:

556:

550:

541:

539:

537:

535:

533:

526:

522:

518:

516:

508:

504:

496:

487:

485:

481:

477:

476:

468:

463:

461:

455:

451:

447:

440:

435:

426:

417:

414:

411:

406:

404:

399:

395:

392:printing and

391:

387:

380:

375:

366:

357:

348:

341:

332:

330:

326:

322:

312:

310:

306:

302:

292:

290:

286:

281:

272:

268:

265:

263:

258:

256:

252:

247:

245:

240:

235:

233:

229:

216:

211:

207:

205:

200:

196:

192:

188:

184:

174:

172:

168:

165:

157:

152:

148:

146:

145:Leeds Pottery

142:

138:

134:

130:

126:

122:

118:

114:

106:

101:

97:

95:

91:

87:

82:

80:

76:

72:

68:

64:

63:Staffordshire

60:

56:

52:

51:

46:

42:

35:

30:

26:

22:

1143:

1126:

1112:

1087:

1082:

1076:google books

1063:

1058:

1042:

1037:

1028:

1012:

1007:

991:

986:

970:

965:

957:

952:

944:

939:

934:, pp. 24-29.

923:

918:

902:

897:

889:

884:

876:

871:

863:

858:

850:

845:

837:

832:

816:

790:

785:

777:

772:

764:

759:

751:

746:

730:

698:

693:

677:

672:

664:

659:

651:

646:

631:

626:

621:, Chapter 10

610:

605:

597:

592:

584:

579:

571:

566:

558:

549:

544:Osborne, 140

524:

523:faïence fine

520:

512:

507:

493:

479:

474:

473:

471:

466:

456:

452:

448:

444:

438:

423:

415:

407:

398:copper plate

384:

379:faience fine

378:

363:

354:

346:

318:

300:

298:

277:

266:

259:

248:

236:

225:

180:

161:

155:

140:

135:in the lead

129:Queen's ware

128:

125:Frog Service

110:

83:

58:

54:

50:faïence fine

48:

40:

39:

25:

1179:British art

403:muffle kiln

351:Lead-powder

222:Development

45:earthenware

1173:Categories

1135:0198661134

1072:0892366702

801:pp. 14-19.

499:References

420:Enamelling

390:underglaze

335:Decoration

280:china clay

260:The young

164:tin-glazed

141:pearl ware

105:loving-cup

79:salt-glaze

75:lead glaze

1144:Creamware

1098:pp. 44–51

1023:pp. 52-58

992:Creamware

913:pp. 20-23

817:Creamware

731:Creamware

709:pp. 9-13.

678:Creamware

611:Creamware

559:Creamware

486:factory.

475:terraglia

467:Terraglia

439:terraglia

394:overglaze

309:porcelain

301:pearlware

295:Pearlware

232:silicosis

195:stoneware

137:overglaze

41:Creamware

460:typology

410:gelatine

103:English

1002:, p. 22

827:, p. 21

741:, p. 20

688:, p. 19

634:(2010)

574:. 1989/

490:Decline

244:biscuit

204:crazing

171:faience

167:faience

156:glacier

67:England

1150:

1133:

1119:

1094:

1070:

1053:(1990)

1049:

1019:

998:

977:

930:

909:

823:

797:

737:

705:

684:

638:

617:

305:cobalt

228:galena

183:Dorset

143:. The

133:cobalt

107:, 1774

981:p. 46

587:2010.

478:, or

315:Forms

239:glaze

191:flint

187:Devon

1148:ISBN

1131:ISBN

1117:ISBN

1092:ISBN

1068:ISBN

1047:ISBN

1017:ISBN

996:ISBN

975:ISBN

928:ISBN

907:ISBN

821:ISBN

795:ISBN

735:ISBN

703:ISBN

682:ISBN

636:ISBN

615:ISBN

519:s.v.

323:and

287:and

253:was

199:lead

185:and

119:and

1175::

1142:,

806:^

714:^

557:,

531:^

206:.

65:,

525:.

23:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.