59:

223:

Anglo-Jews felt that they had worked hard to be considered respectable members of society and the backward image of the

Russian Jew could have threatened this. As a way of controlling the inflow of Russian Jews into the country, the Russo-Jewish Committee was created. This sought to develop communication between Anglo-Jewry and the Russian government. The committee made a grant of £25,000 to allow the Jewish community of Berlin to direct their Jewish refugees to make their way to Russia and was on the condition that none would be sent to England without gaining prior consent from the Anglo-Jewish leadership. This emphasises the impact the influx of the Russian Jew had upon the Anglo-Jewish community.

109:

driving out the

English inhabitants. Of the 1,742 Russian immigrant homes visited by the Sanitary Committee of the Jewish Board of Guardians in 1884, 1,621 did not have access to a sewerage system. Many saw these congregated immigrant areas as 'hotbeds of disease' and feared this would cause epidemics that would be costly to English lives. This gave rise to the view that the Russian Jew was morally and socially degenerative, which in turn fuelled a rise in "anti-alienism". Certainly, this influx of Russian Jews created overcrowding and is considered directly responsible for the high prices of rent and problems of housing.

169:

Liberal government returned to power in 1906, many

Conservatives feared that the Aliens Act would be removed. Considered to be a "law of the land", this restrictionist legislation was not removed. The Liberals amended the act by increasing its flexibility in order to make it less restrictive and easier for people to enter the country. The Liberals disagreed with the Conservative restrictionism and this demonstrates the contested political response in Britain regarding the effects of anti-Jewish Pogroms in Tsarist Russia.

113:

counterparts, thereby underselling the indigenous workforce. Also, for many

British members of society Sunday was deemed a day of rest. Failure to follow this Christian and British tradition was considered scandalous. Historian Bernard Gainer suggested that it was the fact that the alien immigrant was more willing to work on a Sunday, as opposed to conforming to British society, which caused most annoyance. This reinforced British hatred towards the Jewish immigrants.

101:

86:. Meanwhile, it became more difficult to get employed and this exacerbated the increasingly hostile British public opinion. Indeed, a great deal of the anti-Jewish sentiment developed amongst the trade union movements who were worried about this increasing difficulty to get employed. Despite migrating away from their Russian persecutors, the Russian Jews were still blamed for the ills in society, albeit a different society.

135:

Conservative backbenchers put pressure on

Liberal governments to introduce legislation that would restrict the mass influx of central and European Jews into Britain. The Conservatives sought to remove the unchecked immigration system that had allowed so many Russian Jews to enter Britain. This was seen as a direct response to the

313:

Whilst philanthropists and the government often had similar interests regarding the migration and condition of Jews, philanthropic efforts were largely conducted through extra-parliamentary bodies (such as the JCA) and were not influenced by the

British government. This typified the Victorian idea of

293:

There was a fear held by many

British Jews that Jewish immigrants would foul the reputation of the Jewish faith in Britain. This led to philanthropic efforts to help the position and situation of the Jewish immigrants in England and Russia. At the turn of the twentieth century, British philanthropy

187:

There was a prominent Jewish community in existence before the mass influx of

Russian Jewish immigrants. The Anglo-Jewry comprised some of the wealthiest persons in the country. The Anglo-Jews took an interest in the pogroms and heavily impacted the overall British response. After the first wave of

168:

The original restrictionist legislation also posed a significant threat to the

Victorian Liberal tradition of free movement for the peoples of Britain. As part of their free trading policy, the Liberal government believed that Britain should be a safe haven for those suffering persecution. When the

157:

Yet the

Conservative government announced the reintroduction of an Aliens Act in 1905, demonstrating that anti-alien legislation was firmly part of their government policy. The second Aliens Act was introduced early in 1905 as a modified version of its failed predecessor. The 1905 Aliens Act sought

108:

The pogroms convinced many Russian Jews to flee Russia and migrate to the west; however, the huge levels of immigration eventually transformed initial sympathy into general social disaffection. In Britain, for instance, Russian Jews were blamed for changing the landscape in their settled areas and

276:

was the first British newspaper to report on the anti-Jewish persecution and it generated a great deal of public reaction. The paper disapproved of the actions of the Russians and applied pressure for the British government to intervene, occasionally by means of arousing public protest. The paper

226:

The differences in lifestyle and culture fuelled tensions between the native Jews and the immigrants. The newcomers gradually became the majority population in London, which altered the balance of power between the immigrants and the Anglo-Jewry. The immigrants reminded the Anglo-Jewry of their

305:

The JCA was aided by influential Anglo-Jews and intended to improve the living standards of Jews in the Pale of Settlement as well as aid the migration of Jews to agricultural colonies in the Americas. A chief member of the elite involved with the JCA was Lord Rothschild, who was an important

222:

It is worth noting that not all Anglo-Jews welcomed Russian migrants into the country. Though they were sympathetic to the Jews who had suffered such violent treatment, they were concerned about whether this mass influx of Russian Jews could tarnish the reputation of the Jew as a whole. Many

134:

There was a party-political disagreement over what the role of the British government in Russia should be and whether they should intervene. Britain did not intervene and focussed on introducing domestic legislation to control the effects of the pogroms upon Britain. As early as the 1890s,

112:

Russian Jews also vied with the British working-class for jobs. Many immigrants moved to the East End of London and aggravated the already precarious social fabric. Jewish immigrants were more willing to work for longer hours in poorer working conditions at a lower wage than their British

73:

that was of both sympathy and apprehension. These anti-Jewish pogroms sparked much uncertainty for the Russian Jewish population and contributed to high levels of westbound migration from the country. Alongside America, Britain was a place of refuge, in particular major cities such as

154:. He argued that alien immigrants caused overcrowding and tensions in working-class communities, thereby threatening law and order; however, the Liberal opposition condemned this as wrong in both principle and practice. The act was deemed too ruthless and was subsequently rejected.

294:

underwent a shift from focussing on internal affairs to considering external and international events. This focussed particularly upon the hardships endured by Russian Jews. Some of the finest examples of British philanthropy originated from Anglo-Jewry, including that of

244:

was linked by faith to the Russian Jewish cause and sought to stimulate public awareness of the atrocities; however, the newspaper was typically Anglo-Jewish in its attitude, and this was reflected in its reluctance to oppose the introduction of the Aliens Act in 1905.

55:. The Jews of Russia were forced to exist within the Pale of Settlement by the Russian authorities; however, the Pale was not a safe haven for the Jews and they were harshly discriminated against—with the employment of double taxes and the denial of further education.

318:

and 'mutual aid' by placing an emphasis on individuals, families and communities to help each other out. On the domestic level, philanthropy was on a much smaller scale and was focussed primarily on protecting the homeless in informal shelters. The

158:

to give immigration officers the power to exclude those who were deemed detrimental to British society. Immigration officers would then be able to decide, in conjunction with medical inspections, whether or not to let immigrants into the country.

47:

in 1881. There was a second wave of pogroms in the early 20th century, between 1903 and 1906. Despite there being only two waves of pogroms, there had been a culture of anti-Semitism existing for centuries.

127:

227:

history and background. Gutwein suggests that they were the antithesis of their bourgeois-emancipationist ideal and embodied the struggle to bring themselves higher than the status of the proletariat.

339:

continued traditional Conservative lines of an assertive British foreign policy that looked to help Jews abroad whilst maintaining that immigration should not reach pre-1905 levels. Britain’s

373:, in Russian, "grom", which means thunder, suggests a severe level of destruction. The word pogrom derives more directly from the verb "pogromit" which means "break", "smash" and "conquer".

204:

19:

260:, produced it and sought to inform the public over the extent of the Russian atrocities. It gave first hand accounts of the events in Tsarist Russia. In brief, the objective

143:

believed that 'immigration had a deteriorating effect upon moral, financial, and social conditions of the people, which resulted in lowering the general standard of life.'

285:

was a respected and conservative national newspaper, so the fact that it published such sympathetic material suggests many Britons were hostile towards despotic Russia.

240:

was a prominent voice on the persecution of Jews in Tsarist Russia and gives a valuable insight into the Anglo-Jewish outlook on the pogroms. As a Jewish publication,

161:

Although some Conservatives pressured the government to accept restrictionist legislation, some used this as a means of gaining more support in the upcoming

215:

This sympathetic reaction can also be seen after the second wave of pogroms that began in 1903 and continued until 1906. This refers to the meeting at the

165:. The Aliens Act sought to win or retain working-class votes in areas where there was a high volume of immigrants and employment was difficult to achieve.

632:

662:

323:

proclaimed that "such places encourage loafing and illness". This complied with their agenda that protected the reputation of the British Jewry.

256:

and gave up-to-date news and opinions on the pogroms and preserved public interest in the wellbeing of the Russian Jewry. The Jewish Journalist,

277:

also encouraged letters to the editor that frequently complained about the Russian Jewish situation. In 1905, Lucien Wolf wrote a letter to

637:

331:

The pogroms had impacted on Britain in a number of ways. The increase in immigration provoked a media backlash against Jews leading to the

647:

642:

352:

147:

58:

677:

672:

667:

136:

146:

It was not until the 1900s that anti-alien legislation was brought before parliament. In March 1904, Conservative Home Secretary

657:

652:

162:

95:

264:

was to expose "the authentic facts relating to Russia’s persecution of her Jewish and other Nonconformist subjects".

219:(at Langham Place), which was once again designed to stimulate a pro-Jewish British reaction to the Russian pogroms.

310:

orchestrated contributions by helping to raise money and then distributing it via their foreign branches in Russia.

343:

on behalf of the Jews in later years starkly contrasted with the tentative isolationism in late Victorian Britain.

299:

298:. Although he was not English himself, de Hirsch co-operated with much of the British Jewish elite to found the

182:

459:

House of Commons (HC) debate, 3 March 1882, vol 267 cc30-70, 'Persecution of the Jews in Russia – resolution'

272:

provided the largest amount of material relating to the anti-Jewish pogroms. On 11 and 13 January 1882,

340:

193:

566:

S. Johnson, "Breaking or Making the Silence? British Jews and East European Jewish Relief, 1914-17",

307:

295:

532:, 11 January 1882, 13 January 1882, for the first reports of the pogroms in the British press.

189:

236:

140:

8:

336:

603:

The Origins of the British Welfare State: Social Welfare in England and Wales, 1800–1945

468:(HC) debate, 29 January 1902, vol 101 cc1269-911269, 'Immigration of Destitute Aliens'.

63:

52:

44:

126:

216:

32:

370:

130:

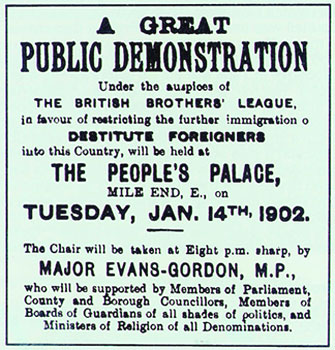

A poster illustrating public opinion and also the standpoint of Major Evans-Gordon

116:

332:

151:

100:

335:. The Act slowed down the immigration of Russian Jews. In the longer term, the

197:

70:

36:

200:, took part in this and advocated an intervention on behalf of Russian Jewry.

626:

543:

Englishmen and Jews : social relations and political culture 1840-1914

178:

40:

257:

208:

203:

83:

315:

268:

79:

18:

505:

The Divided Elite: economics, politics and Anglo-Jewry, 1882–1917

188:

Pogroms in 1881, Anglo-Jewry organised a protest meeting at the

117:

British response to pogroms and their impact on British society

75:

27:

570:, Vol. 30, No. 1, (Oxford University Press: Feb. 2010), p. 95

371:

http://en.wiktionary.org/%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%B3%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%BC

22:

Jewish victims of one of the pogroms in Ekaterinoslav in 1905

89:

448:

The Alien Invasion: the origins of the Aliens Act of 1905

410:

The Alien Invasion: the origins of the Aliens Act of 1905

51:

Most, if not all of the pogroms took place within the

69:The pogroms aroused conflicting public reaction in

545:, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), p. 131

281:arguing that the Jews were unfairly persecuted.

39:, the word pogrom was first used to describe the

624:

230:

412:, (London: Heinemann Educational, 1972), p. 46.

479:Conservative Party attitudes to Jews 1900-1950

435:Conservative Party attitudes to Jews 1900-1950

384:Conservative Party attitudes to Jews 1900-1950

121:

592:Accounts of the Russo-Jewish Committee, 1891

353:British response to the Zanzibar Revolution

43:attacks that followed the assassination of

633:Anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire

192:in London. Prominent Anglo-Jews, such as

605:, (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2004), p. 59.

494:, (Oxford: Clarendon press, 1992), p.115

202:

125:

99:

57:

17:

517:Darkest Russia: A Record of Persecution

90:Effects of pogroms upon British society

663:Jews and Judaism in the United Kingdom

625:

137:anti-Jewish pogroms in Tsarist Russia

507:, (New York: E.J. Brill, 1992), p.13

581:History of the Baron de Hirsch Fund

96:Emancipation of the Jews in England

13:

648:19th century in the United Kingdom

643:19th century in the Russian Empire

399:, (London: P.S. King, 1911), p. 8.

306:philanthropist. The merchant bank

104:Jewish refugees in Liverpool, 1882

14:

689:

386:, 1st edn, (Routledge, 2001), p16

678:Reactions to 19th-century events

673:Reactions to 20th-century events

668:1900s in international relations

397:The Alien problem and its remedy

638:Russia–United Kingdom relations

608:

595:

586:

573:

560:

548:

535:

522:

510:

497:

484:

471:

300:Jewish Colonisation Association

288:

252:was printed as a supplement to

139:. The Conservative politician,

462:

453:

440:

427:

415:

402:

389:

376:

364:

341:interventionist foreign policy

207:An artist's impression of the

183:History of the Jews in England

172:

1:

583:, (Philadelphia: 1935), p.13.

358:

231:Response of the British press

326:

7:

658:1900s in the United Kingdom

653:1900s in the Russian Empire

346:

150:attempted to introduce the

10:

694:

302:(JCA) in England in 1891.

194:Nathaniel Mayer Rothschild

176:

122:British political response

93:

308:N M Rothschild & Sons

296:Baron Maurice de Hirsch

212:

131:

105:

66:

23:

206:

163:1906 General Election

129:

103:

94:Further information:

61:

21:

492:Modern British Jewry

254:The Jewish Chronicle

242:The Jewish Chronicle

237:The Jewish Chronicle

148:Aretas Akers-Douglas

31:is derived from the

337:Balfour Declaration

213:

141:Major Evans-Gordon

132:

106:

67:

64:Pale of Settlement

62:A map showing the

53:Pale of Settlement

24:

519:, 14 August 1891.

45:Tsar Alexander II

685:

618:

615:Jewish Chronicle

612:

606:

599:

593:

590:

584:

577:

571:

564:

558:

552:

546:

539:

533:

526:

520:

514:

508:

501:

495:

488:

482:

475:

469:

466:

460:

457:

451:

444:

438:

431:

425:

419:

413:

406:

400:

393:

387:

380:

374:

368:

321:Jewish Chronicle

35:word погром. In

693:

692:

688:

687:

686:

684:

683:

682:

623:

622:

621:

613:

609:

600:

596:

591:

587:

578:

574:

565:

561:

553:

549:

540:

536:

527:

523:

515:

511:

502:

498:

489:

485:

476:

472:

467:

463:

458:

454:

445:

441:

432:

428:

420:

416:

407:

403:

394:

390:

381:

377:

369:

365:

361:

349:

333:Aliens Act 1905

329:

291:

233:

211:, Langham Place

185:

177:Main articles:

175:

124:

119:

98:

92:

12:

11:

5:

691:

681:

680:

675:

670:

665:

660:

655:

650:

645:

640:

635:

620:

619:

617:, 3 April 1885

607:

594:

585:

572:

568:Modern Judaism

559:

557:, August 1905.

547:

534:

521:

509:

496:

483:

470:

461:

452:

439:

426:

414:

401:

388:

375:

362:

360:

357:

356:

355:

348:

345:

328:

325:

290:

287:

262:Darkest Russia

250:Darkest Russia

248:In the 1890s,

232:

229:

198:Samuel Montagu

174:

171:

123:

120:

118:

115:

91:

88:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

690:

679:

676:

674:

671:

669:

666:

664:

661:

659:

656:

654:

651:

649:

646:

644:

641:

639:

636:

634:

631:

630:

628:

616:

611:

604:

598:

589:

582:

576:

569:

563:

556:

551:

544:

538:

531:

525:

518:

513:

506:

500:

493:

490:G. Alderman,

487:

480:

474:

465:

456:

449:

443:

436:

430:

423:

418:

411:

405:

398:

395:M. J. Landa,

392:

385:

379:

372:

367:

363:

354:

351:

350:

344:

342:

338:

334:

324:

322:

317:

311:

309:

303:

301:

297:

286:

284:

280:

275:

271:

270:

265:

263:

259:

255:

251:

246:

243:

239:

238:

228:

224:

220:

218:

210:

205:

201:

199:

195:

191:

190:Mansion House

184:

180:

170:

166:

164:

159:

155:

153:

149:

144:

142:

138:

128:

114:

110:

102:

97:

87:

85:

81:

77:

72:

65:

60:

56:

54:

49:

46:

42:

38:

34:

30:

29:

20:

16:

614:

610:

602:

597:

588:

580:

575:

567:

562:

554:

550:

542:

541:D. Feldman,

537:

529:

524:

516:

512:

504:

503:D. Gutwein,

499:

491:

486:

478:

473:

464:

455:

447:

442:

434:

429:

421:

417:

409:

404:

396:

391:

383:

382:H. Defries,

378:

366:

330:

320:

312:

304:

292:

289:Philanthropy

282:

278:

273:

267:

266:

261:

253:

249:

247:

241:

235:

234:

225:

221:

217:Queen’s Hall

214:

186:

179:British Jews

167:

160:

156:

145:

133:

111:

107:

68:

50:

41:anti-Semitic

26:

25:

15:

601:B. Harris,

579:S. Joseph,

481:, pp. 18–19

408:B. Gainer,

258:Lucien Wolf

209:Queens Hall

173:Anglo-Jewry

627:Categories

359:References

152:Aliens Act

84:Manchester

555:The Times

530:The Times

477:Defries,

433:Defries,

327:Aftermath

316:self-help

283:The Times

279:The Times

274:The Times

269:The Times

80:Liverpool

450:, p. 52.

446:Gainer,

437:, p. 16.

424:, p. 41.

347:See also

71:Britain

33:Russian

82:, and

76:London

37:Russia

28:Pogrom

528:See

422:ibid

196:and

181:and

629::

78:,

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.