230:. While both of these buildings were built with mud adobe bricks, many characteristics of the bricks differ between the two huacas. Thus, symbolizing two distinct eras in Inka architecture. The bricks varied in many ways such as dimensions, maker marks, soil composition, and mold marks. With that being said, both buildings were constructed in similar ways. Adobe bricks were laid into vertical columns adjacent to one another. Continuing to lay adobe brick columns next to one another in order to construct different sections of a building is characterized as “segmented” construction. The construction of Huaca del Sol is determined to have used over 143 million adobe bricks and the platforms from the Luna are estimated to have required over 50 million adobe blocks. The only uniform characteristic of these adobe bricks, in regard to their dimensional shape, is that "they are wider than they are high." Bricks in the same segment were relatively similar in shape and size, however, there was little symmetry between segments. Many sections of Luna show greater deviation than later columns and structures. As the Inka empire grew in strength and size, adobe bricks became increasingly ubiquitous. Many segments of Luna saw an abundance of deviation from one another. Conversely, Sol, which was built after Luna, has a more well-defined uniformity between adobe bricks used between segments. While the uniform shape of the bricks helped to signify the increasing dominance of the Inka, adobe bricks remained unique in one way. Each brick was marked by its maker on the bottom of the brick. While some markers appear more frequently than others, each symbolizes where the adobe bricks came from.

27:

38:

175:, most, if not all, of the huacas facilitated communication with the supernatural world or had some connection with chthonic powers that were thought to have shaped certain aspects of the region's people. While the Inka huacas were mainly stationary, some of the Andean huacas were actually portable. There are references to huacas being taken into battle or being physically transported to Cusco, capital of the Inka empire. One such huaca is described below:

187:

made it difficult for archaeologists to find and identify them. Shrines and shrine candidates were promptly photographed and compared to other known huacas. Interviews with local village officials helped researchers ensure that the huacas found on the ceques were legitimate. The location of the huacas aided archaeologists in determining what they were used for and what religious ceremonies may have occurred there.

186:

Some huacas were described as shrines, monuments, or temples that were associated with religion. Other huacas were physical aspects of the landscape, such as mountains or large boulders that still held religious and cultural significance. Since the huacas could have been a part of the landscape, this

158:

region and the Inka shared many beliefs when it came to huaca ideology. Pre-empire Inka had a hard time gaining land control in their constant fights with the

Andeans, and only peace was made when the Inka materialized their huacas into a state-controlled system that was common throughout the empire.

164:

It can be argued that the sacred nature of huacas represented the primary connection between Andean ideologies and Inca ideology. Both Andean and Inca ideologies considered huacas as manifestations of both the natural and the supernatural world such as springs, stones, hills and mountains, temples,

202:

became significant centers of shared worship and a point of unification of ethnically and linguistically diverse peoples. They helped to bring unity and common citizenship to often geographically disparate peoples. Since pre-inka times the people developed a system of pilgrimages to these various

122:

These lines were laid out to express the cosmology of the culture and were sometimes aligned astronomically to various stellar risings and settings. These pertained to seasonal ceremonies and time keeping (for the purposes of agriculture and ceremony and record keeping). These ceque lines bear

194:). The Inka elaborated creatively on a preexisting system of religious veneration of the peoples whom they took into their empire. This exchange ensured proper compliance among conquered peoples. The Inka also transplanted and colonized whole groups of persons of Inka background (

170:

The Inka believed in using the huacas as the main agents of sacred and supernatural structural affiliation in their culture, while also using them as political and social tools for manipulation of other cultural groups around them. In the Cusco

180:

The ninth guaca (huaca) was named

Cugiguaman. It was a stone shaped like a falcon which Inca Yupanqui said had appeared to him in a quarry, and he ordered that it be placed on this ceque and that sacrifices be made to

190:

Special compounds were erected at certain huacas where priests composed elaborate rituals and religious ceremonial culture. For instance, the ceremony of the sun was performed at Cusco (

198:) with newly adopted peoples to arrange a better distribution of Inka persons throughout all of their empire in order to avoid widespread resistance. In this instance, huacas and

265:

Manuel Arturo

Izquierdo Pena (2008). "The Muisca Calendar: An approximation to the timekeeping system of the ancient native people of the northeastern Andes of Colombia".

92:

today in almost every district, the city having been built around them. Huacas within the municipal district of Lima are typically fenced off to avoid

336:

Hastings, C. Mansfield, and M. Edward

Moseley. “The Adobes of Huaca Del Sol and Huaca de La Luna.” American Antiquity 40, no. 2 (1975): 196–203.

107:

A huaca could be built along a processional ceremonial line or route, as was done for the enactment of sacred ritual within the capital at

26:

378:

154:(or siq'is lines). When talking about huacas in the Inka empire, it's important to understand that both the Andean people of the

307:

Scott, Amy (2009). "Sacred

Politics: An Examination of Inca Huacas and their use for Political and Social Organization".

65:

can refer to natural locations, such as immense rocks. Some huacas have been associated with veneration and ritual. The

88:

in correlation with the regions populated by the pre-Inka and Inka early civilizations. They can be found in downtown

37:

73:(spirits), one to create it and another to animate it. They would invoke its spirits for the object to function.

293:

373:

280:

119:

and Brian Bauer (UT-Austin) explores the range of debate over their usage and significance.

61:

is an object that represents something revered, typically a monument of some kind. The term

84:

Huacas are commonly located in nearly all regions of Peru outside the deepest parts of the

8:

266:

46:

383:

227:

147:

159:

A common system and a common cultural influence held the Inka empire together:

116:

66:

20:

367:

223:

219:

143:

142:(Inka) Empire, huacas were involved more in prominent monuments, such as the

50:

326:(First ed.). Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. pp. 23–34.

172:

151:

112:

85:

204:

353:

191:

30:

69:

traditionally believed every object has a physical presence and two

33:

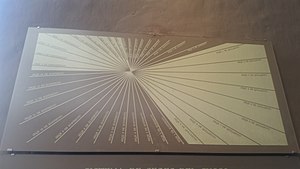

museum marker graphically explaining the Inca Wakas and Seqes system

93:

41:

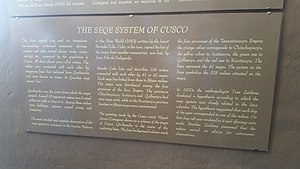

Coricancha museum marker describing the Inca Wakas and Seqes system

358:

271:

247:

123:

significant resemblance to the processional lines among the Maya (

337:

195:

155:

124:

108:

264:

139:

89:

324:

The Sacred

Landscape of the Inca: The Cusco Ceque System

354:

Early

Monumental Architecture on the Peruvian Coast

150:. As stated above, they were also found along the

99:

365:

16:Pre-Columbian South American spiritual markers

130:

165:caves, roads, or trees (D‟Altroy 2002:163).

309:TOTEM: The U.W.O. Journal of Anthropology

270:

258:

218:Two of the greatest huacas built by the

127:), the Chacoans, and the Muisca (Suna).

36:

25:

366:

203:shrines, prior to the introduction of

321:

306:

13:

14:

395:

347:

111:. Such lines were referred to as

76:

210:

379:Indigenous American philosophy

338:https://doi.org/10.2307/279615

330:

315:

300:

240:

1:

233:

7:

10:

400:

19:For the insect genus, see

18:

103:along ceremonial routes

288:Cite journal requires

42:

34:

322:Bauer, Brian (1998).

40:

29:

359:The Solstice Project

252:solsticeproject.org

134:in the Inka Empire

47:Quechuan languages

43:

35:

391:

341:

334:

328:

327:

319:

313:

312:

304:

298:

297:

291:

286:

284:

276:

274:

262:

256:

255:

244:

228:Huaca de la Luna

148:Huaca de la Luna

399:

398:

394:

393:

392:

390:

389:

388:

364:

363:

350:

345:

344:

335:

331:

320:

316:

305:

301:

289:

287:

278:

277:

263:

259:

246:

245:

241:

236:

216:

136:

105:

82:

24:

17:

12:

11:

5:

397:

387:

386:

381:

376:

374:Inca mythology

362:

361:

356:

349:

348:External links

346:

343:

342:

329:

314:

299:

290:|journal=

257:

238:

237:

235:

232:

215:

209:

135:

129:

115:. The work of

104:

98:

81:

75:

67:Quechua people

21:Huaca (beetle)

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

396:

385:

382:

380:

377:

375:

372:

371:

369:

360:

357:

355:

352:

351:

339:

333:

325:

318:

310:

303:

295:

282:

273:

268:

261:

253:

249:

243:

239:

231:

229:

225:

224:Huaca del Sol

221:

214:

208:

206:

201:

197:

193:

188:

184:

182:

176:

174:

168:

166:

160:

157:

153:

149:

145:

144:Huaca del Sol

141:

133:

128:

126:

120:

118:

114:

110:

102:

97:

95:

91:

87:

79:

74:

72:

68:

64:

60:

56:

52:

51:South America

48:

39:

32:

28:

22:

332:

323:

317:

308:

302:

281:cite journal

260:

251:

242:

217:

212:

199:

189:

185:

179:

177:

173:ceque system

169:

163:

161:

152:ceque system

137:

131:

121:

106:

100:

86:Amazon basin

83:

77:

70:

62:

58:

54:

44:

205:Catholicism

117:Tom Zuidema

368:Categories

234:References

192:Inti Raymi

31:Coricancha

272:0812.0574

222:were the

200:pacarinas

226:and the

146:and the

94:graffiti

71:camaquen

384:Animism

138:In the

80:in Peru

45:In the

248:"Home"

213:Huacas

211:Moche

196:Mitmaq

132:Huacas

113:ceques

101:Huacas

78:Huacas

267:arXiv

220:Moche

156:Andes

125:sacbe

109:Cusco

63:huaca

59:wak'a

55:huaca

294:help

140:Inca

90:Lima

53:, a

181:it.

167:"

57:or

49:of

370::

285::

283:}}

279:{{

250:.

207:.

183:"

96:.

340:.

311:.

296:)

292:(

275:.

269::

254:.

178:"

162:"

23:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.