96:

priestess, the only political office able to be held by a woman for social mobility. Female patronage of public construction projects was related to priesthoods in

Pompeii; these public responsibilities, paired with familial status, may have given women the authority or opportunity to bequest monuments to communities. As priestesses, these women guarded long-held communal traditions. They used their patronage to erect monuments that reflected their or their families' predominance and social standing in the town. In exchange, these prominent patrons were honored with honorific sculptures in life and donations of land for tombs or money for funerals after death . The disparities between Mamia, a 1st-century public priestess in Pompeii from a prominent family in Herculaneum, officially sanctioned tomb, and Eumachia's private tomb show how diverse the social response may be. However, the range of social functions depicted in sculptures of women is more limited: this reflects both their actual place in society and the ideal of womanly behavior (for the elite, at least). The Romans were caught in a bind when publicly displaying their women in portrait statues: The ideal of the sexually faithful, domestically oriented, heir-producing matron, who was reluctant to be seen in public, clashed with the reality of the politically active women of the imperial court and the financially significant female municipal patrons in towns across the empire. Funerary inscriptions emphasize women's domestic and familial values: chastity, material fidelity, wifely and motherly devotion, and attention to household chores.

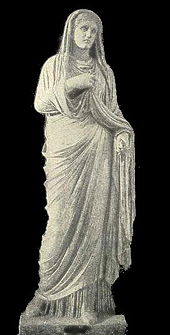

209:, whose statues popularized the representation of the stola. Family members adopting aspects of the emperor's physiognomy emphasize family cohesion in imperial portraits. The wavy strands of hair separated in the center and pushed back from Eumachia's face imply that the image incorporates elements of the portraiture of imperial ladies. Moreover, her individualizing characteristics highlight the classicizing traits: her small mouth, slightly bent head revealing her delicate neck, and veiled hair. Her stance is quite dynamic in that her right knee is slightly bent, and her left foot is in the front, reflecting a trait that suggests more active body language in that she looks to step off her pedestal while having a closed form and wearing heavy garments. She is also gazing down on her audience that opposes the social mores and highlights the discrepancy between ideal and actual. Despite her wealth, she still had to balance the demands on her to adhere to conventional fashions with the more rebellious elements of her portrait.

113:

forum. The porticus is a four-sided colonnade surrounding a large courtyard. Finally, the crypta is a large corridor behind the porticus on the north east and south sides, separated from the porticus by a single wall that has windows that were probably once shuttered, in earlier descriptions, there were even cisterns, vats, basins, and stone tables in the courtyard. In the center of the court yard, that is said to have been paved of stone slabs, there is a stone block with an iron ring that covered an underground cistern. The dating for the building is somewhat vague, coming in somewhere between 9 BC and 22 AD. A Marcus

Numistrius Fronto had a post-mortem inscription dedicated to him on the building, and he held the office of duumvir in 3 AD. For this reason it is believed that he was more likely to have been Eumachia's husband rather than her son, at the same time, there is an idealized statue of Eumachia dressed in a tunic, stola, and cloak in a niche toward the back of the building.

178:

117:

137:

190:

105:

27:

222:

Such references to the central authority solidified her elite reputation in

Pompeii, emphasizing her importance to the fullers who sponsored the statue and the general public who benefited from the new complex. The rough translation of this inscription is: "to Eumachia, daughter of Lucius, public

112:

The building of

Eumachia, the largest building near the forum of Pompeii, is commonly broken down into three parts, the chalcidicum, the porticus, and the crypta. The chalcidicum encompasses the front of the building and is an important part of the continuous portico running along the east of the

132:

done off site because of the smell, a headquarters for the fullers guild, where they did everything involved with the fulling process, with the idea that smells were of little concern in an ancient city before the invention of modern sewage, a private place for city businessmen, especially those

148:

The building as a whole is dedicated to

Augustian Concord and Piety, thought to be in the image if Livia, one of the first women in Pompeii to have their own honorific statues. In front of the building, there are bases of what were once statues of Romulus and Aeneas. Paintings of the street of

144:

Detailed archaeological investigation of the entrance suggests the building cannot have been used as an active marketplace. If the building of

Eumachia was used as a cloth vendor or market, the entrances would be wider and placed in the middle of their respective walls. The entrances at

95:

Eumachia is essential as an example of how a Roman woman of non-imperial/non-aristocratic descent could become an important figure in a community and be involved in public affairs. She is seen as a representative for the increasing involvement of women in politics, using the power of a public

212:

The placing of

Eumachia's honorific statue extends from the fountain to the porticos, as well as the high level of craftsmanship. Also, the idealizing portrait characteristics emphasize her link to the empress and her fulfillment of Augustan

153:. In front of the building, there are bases of what were once statues of Romulus and Aeneas. Paintings of the street of Abundance, where the building is located, show Aeneas leading his family from Troy and Romulus holding a

68:

The

Numistrii were one of Pompeii's oldest and most powerful families. All that is certain is that Eumachia was able to use her wealth and social standing to obtain the position of public priestess of the goddess

63:

Eumachia was the daughter of Lucius

Eumachius, who amassed a large fortune as a manufacturer of bricks, tiles and amphorae. She married Marcus Numistrius Fronto, who may have held the important office of

133:

engaged in the wool trade, a private place for transacting business and relaxation within the crypta and porticus, or a place for wool exchange where goods in large quantities were sold in auction.

169:, which influenced the wealthy people of her time period. In the early Roman empire, wealthy citizens increasingly donated their wealth to groups in their communities in return for public honors.

124:

The purpose of the building is unknown to modern historians, with a number of possible purposes having been suggested, such as the following: A market place for goods, especially those sold by the

205:, in Hellenistic style. Eumachia has an idealized portrait. Palla, delicate women's poses, features, and material, was the aim of Rome's social control approach, which alludes to

145:

Eumachia allowed for strict observance of those who entered from the N and main entrances through porter's lodges which is uncommon in markets such as

Macellum and the Basilica.

165:

Using her immense wealth to finance a large public works project, Eumachia was engaging in the socio-political phenomenon of voluntary gift-giving known as

177:

479:

128:' guild of which Eumachia was the matron, a headquarters for the fullers' guild, where they washed, stretched and dyed wool, with the actual

604:

810:

771:

Boatwright, Mary T., Daniel J. Gargola, and Richard J. Talbert. A Brief History of the Romans. New York: Oxford UP, 2006. 217.

825:

593:

Hornblower, Simon, and Antony Spawforth, eds. "Pompeii." Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1998.

40:(1st century AD) was a Roman business entrepreneur and priestess. She served as the public priestess of Venus Pompeiana in

108:

Ruins of the building funded by Eumachia, with portions of the inscription visible on the horizontal light-colored stone

751:

709:

630:

570:

502:

455:

417:

264:

805:

497:. Curran, Brian., J. Paul Getty Museum., World Monuments Fund (New York, N.Y.). Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

116:

820:

224:

48:

guild. She is known primarily from inscriptions on a large public building which she financed and dedicated to

815:

800:

795:

149:

Abundance, where the building is located, show Aeneas leading his family from Troy and Romulus holding a

136:

245:

Lefkowitz, Mary R., and Maureen B. Fant. Women's Life in Greece and Rome. London: Duckworth, 1982. 259.

75:

84:

621:

230:

A copy of the statue is in Pompeii while the original is at the Naples Archaeological Museum.

53:

193:

The statue of Eumachia at the Building in Pompeii. The inscription is present on the base.

8:

543:

473:

390:

336:

297:

747:

705:

626:

576:

566:

535:

508:

498:

461:

451:

423:

413:

328:

289:

260:

70:

739:

697:

674:

670:

616:

382:

20:

198:

731:

689:

189:

182:

743:

701:

789:

539:

465:

332:

293:

580:

512:

427:

154:

150:

214:

547:

527:

340:

316:

301:

281:

166:

394:

370:

450:. Cooley, M. G. L. (Melvin George Lowe) (Second ed.). London.

386:

129:

41:

31:

49:

321:

Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. Supplementary Volumes

317:"Portrait Statues as Models for Gender Roles in Roman Society"

104:

206:

202:

125:

80:

45:

255:

James, Sharon L.; Dillon, Sheila, eds. (13 February 2012).

26:

732:"The Reuse and Redisplay of Honorific Statues in Pompeii"

690:"The Reuse and Redisplay of Honorific Statues in Pompeii"

259:. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 405.

73:(the city's patron goddess), and she became a successful

87:

which consisted of tanners, dyers and clothing-makers.

239:

223:

priestess of Pompeian Venus, from the fullers." See

661:Kampen, Natalie Boymel (1988). "The Muted Other".

780:CIL, vol. X, no. 813; Pompeii, first century A.D.

528:"Female Patrons and Honorific Statues in Pompeii"

282:"Female Patrons and Honorific Statues in Pompeii"

787:

140:Entrance of The Building of Eumachia in Pompeii

738:, Cambridge University Press, pp. 24–50,

736:Reuse and Renovation in Roman Material Culture

696:, Cambridge University Press, pp. 24–50,

694:Reuse and Renovation in Roman Material Culture

565:. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

371:"The Building of Eumanchia: A Reconsideration"

120:Statue of priestess Eumachia Building Pompeii

254:

30:The statue erected in honor of Eumachia at

729:

687:

648:Women and the Roman City in the Latin West

602:

525:

478:: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (

279:

620:

257:A companion to women in the ancient world

227:: "EVMACHIAE L F SACERD PVBL FVLLONES,".

181:The statue of Eumachia on display at the

79:of the economically significant guild of

613:Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics

188:

176:

135:

115:

103:

25:

622:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.2533

532:Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome

407:

368:

286:Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome

99:

788:

660:

645:

560:

445:

314:

90:

492:

448:Pompeii and Herculaneum: a sourcebook

441:

439:

437:

364:

362:

360:

358:

356:

354:

352:

350:

13:

58:

14:

837:

811:Priestesses from the Roman Empire

434:

410:The wool trade of ancient Pompeii

347:

563:Pompeii: public and private life

369:Moeller, Walter O. (July 1972).

16:Roman entrepreneur and priestess

774:

765:

723:

681:

654:

639:

596:

587:

554:

375:The University of Chicago Press

675:10.1080/00043249.1988.10792387

519:

486:

401:

308:

273:

248:

225:Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

1:

233:

160:

44:as well as the matron of the

826:Ancient Roman businesspeople

7:

730:Longfellow, Brenda (2018),

688:Longfellow, Brenda (2018),

526:Longfellow, Brenda (2014).

408:Moeller, Walter O. (1976).

280:Longfellow, Brenda (2014).

10:

842:

603:Zuiderhoek, Arjan (2016).

18:

744:10.1017/9781108582513.002

702:10.1017/9781108582513.002

495:The lost world of Pompeii

197:Eumachia is dressed in a

172:

19:For the plant genus, see

185:during a 2013 exhibition

806:1st-century Roman women

646:Cooley, Alison (2013).

446:Cooley, Alison (2014).

315:Davies, Glenys (2008).

194:

186:

141:

121:

109:

34:

821:Ancient businesswomen

561:Zanker, Paul (1998).

493:Amery, Colin (2002).

192:

180:

139:

119:

107:

29:

100:Building of Eumachia

816:People from Pompeii

91:Social significance

801:1st-century Romans

796:1st-century clergy

195:

187:

142:

122:

110:

54:Concordia Augusta.

35:

534:. 59/60: 81–101.

412:. Leiden: Brill.

288:. 59/60: 81–101.

201:over a tunic and

833:

781:

778:

772:

769:

763:

762:

761:

760:

727:

721:

720:

719:

718:

685:

679:

678:

658:

652:

651:

643:

637:

636:

624:

600:

594:

591:

585:

584:

558:

552:

551:

523:

517:

516:

490:

484:

483:

477:

469:

443:

432:

431:

405:

399:

398:

366:

345:

344:

312:

306:

305:

277:

271:

270:

252:

246:

243:

21:Eumachia (plant)

841:

840:

836:

835:

834:

832:

831:

830:

786:

785:

784:

779:

775:

770:

766:

758:

756:

754:

728:

724:

716:

714:

712:

686:

682:

659:

655:

644:

640:

633:

601:

597:

592:

588:

573:

559:

555:

524:

520:

505:

491:

487:

471:

470:

458:

444:

435:

420:

406:

402:

367:

348:

313:

309:

278:

274:

267:

253:

249:

244:

240:

236:

175:

163:

102:

93:

71:Venus Pompeiana

61:

59:Name and family

24:

17:

12:

11:

5:

839:

829:

828:

823:

818:

813:

808:

803:

798:

783:

782:

773:

764:

752:

722:

710:

680:

653:

638:

631:

595:

586:

571:

553:

518:

503:

485:

456:

433:

418:

400:

387:10.2307/503926

381:(3): 323–327.

346:

307:

272:

265:

247:

237:

235:

232:

183:British Museum

174:

171:

162:

159:

101:

98:

92:

89:

60:

57:

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

838:

827:

824:

822:

819:

817:

814:

812:

809:

807:

804:

802:

799:

797:

794:

793:

791:

777:

768:

755:

753:9781108582513

749:

745:

741:

737:

733:

726:

713:

711:9781108582513

707:

703:

699:

695:

691:

684:

676:

672:

668:

664:

657:

649:

642:

634:

632:9780199381135

628:

623:

618:

614:

610:

606:

599:

590:

582:

578:

574:

572:0-674-68966-6

568:

564:

557:

549:

545:

541:

537:

533:

529:

522:

514:

510:

506:

504:0-89236-687-7

500:

496:

489:

481:

475:

467:

463:

459:

457:9780415666794

453:

449:

442:

440:

438:

429:

425:

421:

419:90-04-04494-9

415:

411:

404:

396:

392:

388:

384:

380:

376:

372:

365:

363:

361:

359:

357:

355:

353:

351:

342:

338:

334:

330:

326:

322:

318:

311:

303:

299:

295:

291:

287:

283:

276:

268:

266:9781444355000

262:

258:

251:

242:

238:

231:

228:

226:

221:

218:

217:

210:

208:

204:

200:

191:

184:

179:

170:

168:

158:

156:

152:

146:

138:

134:

131:

127:

118:

114:

106:

97:

88:

86:

82:

78:

77:

72:

67:

56:

55:

51:

47:

43:

39:

33:

28:

22:

776:

767:

757:, retrieved

735:

725:

715:, retrieved

693:

683:

666:

662:

656:

647:

641:

612:

608:

605:"Euergetism"

598:

589:

562:

556:

531:

521:

494:

488:

447:

409:

403:

378:

374:

324:

320:

310:

285:

275:

256:

250:

241:

229:

219:

215:

211:

196:

164:

155:Spolia opima

151:Spolia opima

147:

143:

123:

111:

94:

74:

65:

62:

37:

36:

663:Art Journal

327:: 207–220.

790:Categories

759:2022-12-01

717:2022-12-01

609:Euergetism

234:References

167:euergetism

161:Euergetism

669:: 15–19.

540:0065-6801

474:cite book

466:841187018

333:1940-0977

294:0065-6801

650:. Brill.

581:39143166

548:44981973

513:51311096

341:40379355

302:44981973

76:patronus

38:Eumachia

428:2844987

130:fulling

126:fullers

81:fullers

66:duovir.

46:Fullers

42:Pompeii

32:Pompeii

750:

708:

629:

579:

569:

546:

538:

511:

501:

464:

454:

426:

416:

395:503926

393:

339:

331:

300:

292:

263:

173:Statue

83:, the

50:Pietas

544:JSTOR

391:JSTOR

337:JSTOR

298:JSTOR

216:mores

207:Livia

203:stola

199:palla

85:guild

748:ISBN

706:ISBN

627:ISBN

577:OCLC

567:ISBN

536:ISSN

509:OCLC

499:ISBN

480:link

462:OCLC

452:ISBN

424:OCLC

414:ISBN

329:ISSN

290:ISSN

261:ISBN

52:and

740:doi

698:doi

671:doi

617:doi

383:doi

792::

746:,

734:,

704:,

692:,

667:47

665:.

625:.

615:.

611:.

607:.

575:.

542:.

530:.

507:.

476:}}

472:{{

460:.

436:^

422:.

389:.

379:76

377:.

373:.

349:^

335:.

323:.

319:.

296:.

284:.

157:.

742::

700::

677:.

673::

635:.

619::

583:.

550:.

515:.

482:)

468:.

430:.

397:.

385::

343:.

325:7

304:.

269:.

220:.

23:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.