139:(forms of defamation) to determine if it adequately protects the privacy of the individual. The authors conclude that this body of law is insufficient to protect the privacy of the individual because it "deals only with damage to reputation." In other words, defamation law, regardless of how widely circulated or unsuited to publicity, requires that the individual suffer a direct effect in his or her interaction with other people. The authors write: "However painful the mental effects upon another of an act, though purely wanton or even malicious, yet if the act itself is otherwise lawful, the suffering inflicted is

50:

61:

209:

In general, then, the matters of which the publication should be repressed may be described as those which concern the private life, habits, acts, and relations of an individual, and have no legitimate connection with his fitness for a public office which he seeks or for which he is suggested, . . .

156:

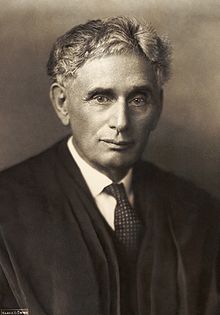

Warren and

Brandeis then discuss the origin of what they called a "right to be let alone". They explain that the right of property provides the foundation for the right to prevent publication. But at the time the right of property only protected the right of the creator to any profits derived from

117:

The press is overstepping in every direction the obvious bounds of propriety and of decency. Gossip is no longer the resource of the idle and of the vicious, but has become a trade, which is pursued with industry as well as effrontery. To satisfy a prurient taste the details of sexual relations are

173:

Furthermore, Warren and

Brandeis suggest the existence of a right to privacy based on the jurisdictional justifications used by the courts to protect material from publication. The article states, "where protection has been afforded against wrongful publication, the jurisdiction has been asserted,

100:

The first three paragraphs of the essay describe the development of the common law with regard to life and property. Originally, the common law "right to life" only provided a remedy for physical interference with life and property. But later, the scope of the "right to life" expanded to recognize

177:

Warren and

Brandeis proceed to point out that: "This protection of implying a term in a contract, or of implying a trust, is nothing more nor less than a judicial declaration that public morality, private justice, and general convenience demand the recognition of such a rule." In other words, the

169:

If this conclusion is correct, then existing law does afford "a principle which may be invoked to protect the privacy of the individual from invasion either by the too enterprising press, the photographer, or the possessor of any other modern device for recording or reproducing scenes or sounds."

96:

Warren and

Brandeis begin their article by introducing the fundamental principle that "the individual shall have full protection in person and in property." They acknowledge that this is a fluid principle that has been reconfigured over the centuries as a result of political, social, and economic

264:

The matter came to a head when the newspapers had a field day on the occasion of the wedding of a daughter, and Mr. Warren became annoyed. It was an annoyance for which the press, the advertisers and the entertainment industry of

America were to pay dearly over the next seventy years. Mr. Warren

112:

Beginning with the fourth paragraph, Warren and

Brandeis explain the desirability and necessity that the common law adapt to recent inventions and business methods—namely, the advent of instantaneous photography and the widespread circulation of newspapers, both of which have contributed to the

189:

Warren and

Brandeis argue that courts have no justification to prohibit the publication of such a letter, under existing theories or property rights. Rather, they argue, "the principle which protects personal writings and any other productions of the intellect or the emotions, is the right to

198:

Finally, Warren and

Brandeis consider the remedies and limitations of the newly conceived right to privacy. The authors acknowledge that the exact contours of the new theory are impossible to determine, but several guiding principles from tort law and intellectual property law are applicable.

152:

to determine if its principles and doctrines may sufficiently protect the privacy of the individual. Warren and

Brandeis concluded that "the protection afforded to thoughts, sentiments, and emotions, expressed through the medium of writing or of the arts, so far as it consists in preventing

255:

described Warren and

Brandeis' essay as "perhaps the most famous and certainly the most influential law review article ever written", attributing the recognition of the common law right of privacy by some 15 state courts in the United States directly to "The Right to Privacy". In 1960,

185:

Yet, the article raises a problematic scenario where a casual recipient of a letter, who did not solicit the correspondence, opens and reads the letter. Simply by receiving, opening, and reading a letter the recipient does not create any contract or accept any trust.

388:, v. 21, n. 21, pp. 1–39 (1979), p. 1 ("The right to privacy is, as a legal concept, a fairly recent invention. It dates back to a law review article published in December of 1890 by two young Boston lawyers, Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis.").

127:

The authors state the purpose of the article: "It is our purpose to consider whether the existing law affords a principle which can properly be invoked to protect the privacy of the individual; and, if it does, what the nature and extent of such protection is."

235:

As a closing note, Warren and Brandeis suggest that criminal penalties should be imposed for violations of the right to privacy, but the pair decline to further elaborate on the matter, deferring instead to the authority of the legislature.

215:

The right to privacy does not prohibit the communication of any matter, though in its nature private, when the publication is made under circumstances which would render it a privileged communication according to the law of slander and

71:

Although credited to both Louis Brandeis and Samuel Warren, the article was apparently written primarily by Brandeis, on a suggestion of Warren based on his "deep-seated abhorrence of the invasions of social privacy."

80:

in American law, attributed the specific incident to an intrusion by journalists on a society wedding, but in truth it was inspired by more general coverage of intimate personal lives in society columns of newspapers.

250:

noted in 1916, some 25 years after the essay's publication, that Warren and Brandeis were responsible for "nothing less than adding a chapter to our law." Some decades later, in a highly cited article of his own,

157:

the publication. The law did not yet recognize the idea that there was value in preventing publication. As a result, the ability to prevent publication did not clearly exist as a right of property.

633:

546:

206:"The right to privacy does not prohibit any publication of matter which is of public or general interest." Warren and Brandeis elaborate on this exception to the right to privacy by stating:

166:

asserted that its decision was based on the protection of property, a close examination of the reasoning reveals the existence of other unspecified rights—that is, the right to be let alone.

118:

spread broadcast in the columns of the daily papers. To occupy the indolent, column upon column is filled with idle gossip, which can only be procured by intrusion upon the domestic circle.

113:

invasion of an individual's privacy. Warren and Brandeis take this opportunity to excoriate the practices of journalists of their time, particularly aiming at society gossip pages:

694:

291:

for being privacy law's chief architect but calling for privacy law to "regain some of Warren and Brandeis's dynamism." The Olmstead decision was later overruled in the

37:. It is "one of the most influential essays in the history of American law" and is widely regarded as the first publication in the United States to advocate a right to

174:

not on the ground of property, or at least not wholly on that ground, but upon the ground of an alleged breach of an implied contract or of a trust or confidence."

570:

543:

273:, upon which the two men collaborated. It has come to be regarded as the outstanding example of the influence of legal periodicals upon the American law.

160:

The authors proceed to examine case law regarding a person's ability to prevent publication. Warren and Brandeis observed that, although the court in

232:

With regard to remedies, a plaintiff may institute an action for tort damages as compensation for injury or, alternatively, request an injunction.

406:

Freund, Privacy: One Concept or Many, in NOMOS XIII: PRIVACY 182, 184 (Pennock & Chapman eds. 1971), as cited in Glancy, 1979, p. 5.

109:—fear of actual bodily injury. Similarly, the concept of property expanded from protecting only tangible property to intangible property.

260:'s article "Privacy" (itself enormously influential in the field), described the circumstances of the article and its importance thusly:

679:

377:

265:

turned to his recent law partner, Louis D. Brandeis, who was destined not to be unknown to history. The result was a noted article,

219:

The law would probably not grant any redress for the invasion of privacy by oral publication in the absence of special damage.

244:

The article "immediately" received a strong reception and continues to be a touchstone of modern discussions of privacy law.

622:

153:

publication, is merely an instance of the enforcement of the more general right of the individual to be let alone."

699:

511:

567:

182:

that contracts implied a provision against publication or that a relationship of trust mandated nondisclosure.

210:

and have no legitimate relation to or bearing upon any act done by him in a public or quasi public capacity.

684:

593:

Palmer, Vernon Valentine (Jan 2011). "Three Milestones in the History of Privacy in the United States".

428:

288:

73:

689:

279:

222:

The right to privacy ceases upon the publication of the facts by the individual, or with his consent.

149:

162:

145:" (a loss or harm from something other than a wrongful act and which occasions no legal remedy).

49:

579:

529:

433:

324:

292:

141:

358:

674:

669:

374:

8:

616:"The Right to Privacy" by Louis D. Brandeis and Samuel Warren: A Digital Critical Edition

361:"The Right to Privacy" by Louis D. Brandeis and Samuel Warren: A Digital Critical Edition

53:

24:

494:

277:

Contemporary scholar Neil M. Richards notes that this article and Brandeis' dissent in

257:

252:

33:

287:

note that Warren and Brandeis popularized privacy with the article, giving credit to

470:

344:

316:

574:

550:

381:

102:

419:, Volume 1 (Urofsky & Levy eds. 1971), as cited in Glancy, 1979, p. 6.

320:

64:

28:

663:

476:

284:

179:

490:

247:

23:" (4 Harvard L.R. 193 (Dec. 15, 1890)) is a law review article written by

77:

650:

85:

105:—a protection against actual bodily injury—gave rise to the action of

283:

together "are the foundation of American privacy law". Richards and

583:, v. 98, pp. 1887–1924, disc. pp. 1887–1888 and 1924.

474:, v. 67, pp. 428–429 (1891) and "The Defense of Privacy",

228:

The absence of "malice" in the publisher does not afford a defense.

41:, articulating that right primarily as a "right to be let alone".

132:

106:

38:

16:

1890 law review article by Samuel D. Warren II and Louis Brandeis

557:, v. 63, n. 5, pp. 1295–1352, pp. 1295–1296.

468:

Glancy 1979, pp. 6–7, citing "The Right to Be Let Alone",

415:

Letter from Brandeis to Warren (April 8, 1905), p. 303 in

654:

136:

225:

The truth of the matter published does not afford a defense.

148:

Second, in the next several paragraphs, the authors examine

101:

the "legal value of sensations." For example, the action of

88:

standards, comprising only 7222 words, excluding citations.

60:

417:

Letters of Louis D. Brandeis, 1870–1907: Urban Reformer

501:, p. 70 (1956), cited by Glancy 1979, p. 1.

695:

Works originally published in the Harvard Law Review

455:See Glancy, 1979, p. 6, referencing A. Mason,

618:, University of Massachusetts Press, forthcoming.

364:, University of Massachusetts Press, forthcoming.

661:

76:, in writing his own influential article on the

122:

629:, v. 21, n. 1, pp. 1–39 (1979).

315:

131:First, Warren and Brandeis examine the law of

91:

634:"The Puzzle of Brandeis, Privacy, and Speech"

544:"The Puzzle of Brandeis, Privacy, and Speech"

640:, v. 63, n. 5, pp. 1295–1352

239:

84:"The Right to Privacy" is brief by modern

566:Neil M. Richards & Daniel J. Solove,

480:v. 266, n. 200 (Feb. 7, 1891).

59:

48:

623:"The Invention of the Right to Privacy"

568:"Prosser's Privacy Law: A Mixed Legacy"

391:

375:"The Invention of the Right to Privacy"

662:

592:

595:Tulane European & Civil Law Forum

311:

309:

397:Warren & Brandeis, paragraph 1.

13:

608:

527:William L. Prosser, "Privacy", 48

14:

711:

644:

306:

680:Privacy law in the United States

202:The applicable limitations are:

586:

560:

536:

521:

504:

483:

462:

651:"The Right to Privacy" article

449:

440:

422:

409:

400:

373:See, e.g., Dorothy J. Glancy,

367:

351:

193:

1:

516:Law and Contemporary Problems

497:(1916), quoted in A. Mason,

446:See Glancy, 1979, p. 6.

31:, and published in the 1890

7:

499:Brandeis: A Free Man's Life

457:Brandeis: A Free Man's Life

294:Katz v United States (1967)

92:Introduction and background

10:

716:

510:Melville B. Nimmer, 1954,

44:

280:Olmstead v. United States

150:intellectual property law

512:"The Right of Publicity"

300:

163:Prince Albert v. Strange

700:Works by Louis Brandeis

240:Reception and influence

325:"The Right to Privacy"

275:

212:

120:

68:

57:

638:Vanderbilt Law Review

580:California Law Review

555:Vanderbilt Law Review

530:California Law Review

434:California Law Review

323:(December 15, 1890).

262:

207:

142:damnum absque injuria

115:

63:

52:

614:Susan E. Gallagher,

459:, p. 70 (1956).

357:Susan E. Gallagher,

267:The Right to Privacy

21:The Right to Privacy

685:Works about privacy

621:Dorothy J. Glancy,

54:Samuel D. Warren II

25:Samuel D. Warren II

632:Neil M. Richards,

627:Arizona Law Review

573:2011-06-29 at the

549:2013-12-03 at the

542:Neil M. Richards,

386:Arizona Law Review

380:2010-07-22 at the

329:Harvard Law Review

271:Harvard Law Review

258:William L. Prosser

253:Melville B. Nimmer

123:Defining "privacy"

69:

58:

34:Harvard Law Review

178:courts created a

707:

690:Legal literature

603:

602:

590:

584:

564:

558:

540:

534:

525:

519:

508:

502:

487:

481:

471:Atlantic Monthly

466:

460:

453:

447:

444:

438:

431:, "Privacy", 48

426:

420:

413:

407:

404:

398:

395:

389:

371:

365:

359:Introduction to

355:

349:

348:

345:Internet Archive

342:

340:

313:

715:

714:

710:

709:

708:

706:

705:

704:

660:

659:

647:

611:

609:Further reading

606:

591:

587:

575:Wayback Machine

565:

561:

551:Wayback Machine

541:

537:

526:

522:

509:

505:

495:William Chilton

488:

484:

467:

463:

454:

450:

445:

441:

429:William Prosser

427:

423:

414:

410:

405:

401:

396:

392:

382:Wayback Machine

372:

368:

356:

352:

338:

336:

321:Brandeis, Louis

314:

307:

303:

289:William Prosser

242:

196:

125:

94:

74:William Prosser

47:

17:

12:

11:

5:

713:

703:

702:

697:

692:

687:

682:

677:

672:

658:

657:

646:

645:External links

643:

642:

641:

630:

619:

610:

607:

605:

604:

585:

559:

535:

520:

518:, p. 203.

503:

482:

461:

448:

439:

421:

408:

399:

390:

366:

350:

317:Warren, Samuel

304:

302:

299:

297:court ruling.

241:

238:

230:

229:

226:

223:

220:

217:

213:

195:

192:

124:

121:

93:

90:

65:Louis Brandeis

46:

43:

29:Louis Brandeis

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

712:

701:

698:

696:

693:

691:

688:

686:

683:

681:

678:

676:

673:

671:

668:

667:

665:

656:

652:

649:

648:

639:

635:

631:

628:

624:

620:

617:

613:

612:

600:

596:

589:

582:

581:

576:

572:

569:

563:

556:

552:

548:

545:

539:

532:

531:

524:

517:

513:

507:

500:

496:

492:

486:

479:

478:

477:The Spectator

473:

472:

465:

458:

452:

443:

436:

435:

430:

425:

418:

412:

403:

394:

387:

383:

379:

376:

370:

363:

362:

354:

346:

334:

330:

326:

322:

318:

312:

310:

305:

298:

296:

295:

290:

286:

285:Daniel Solove

282:

281:

274:

272:

268:

261:

259:

254:

249:

245:

237:

233:

227:

224:

221:

218:

214:

211:

205:

204:

203:

200:

191:

187:

183:

181:

180:legal fiction

175:

171:

167:

165:

164:

158:

154:

151:

146:

144:

143:

138:

134:

129:

119:

114:

110:

108:

104:

98:

89:

87:

82:

79:

78:privacy torts

75:

66:

62:

55:

51:

42:

40:

36:

35:

30:

26:

22:

637:

626:

615:

598:

594:

588:

578:

562:

554:

538:

533:383, at 384.

528:

523:

515:

506:

498:

491:Roscoe Pound

489:Letter from

485:

475:

469:

464:

456:

451:

442:

432:

424:

416:

411:

402:

393:

385:

369:

360:

353:

343:– via

337:. Retrieved

335:(5): 193–220

332:

328:

293:

278:

276:

270:

266:

263:

248:Roscoe Pound

246:

243:

234:

231:

208:

201:

197:

188:

184:

176:

172:

168:

161:

159:

155:

147:

140:

130:

126:

116:

111:

99:

95:

83:

70:

32:

20:

18:

675:Privacy law

670:1890 essays

437:383 (1960).

194:Limitations

664:Categories

190:privacy."

86:law review

269:, in the

67:, c. 1916

56:, c. 1875

601:: 67–97.

571:Archived

547:Archived

378:Archived

97:change.

133:slander

107:assault

103:battery

45:Article

39:privacy

339:4 June

216:libel.

655:JSTOR

301:Notes

137:libel

341:2021

135:and

27:and

653:at

493:to

666::

636:,

625:,

599:26

597:.

577:,

553:,

514:,

384:,

333:IV

331:.

327:.

319:;

308:^

347:.

19:"

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.